To Everything There is a Season (Agriculture)

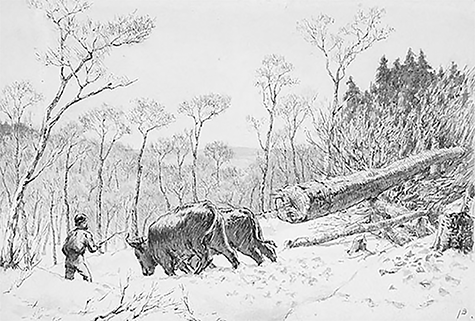

Settler clearing the land with oxen. Courtesy G Harvey.

by Gerry Pierce

AXE & OX: PIONEER AGRICULTURE IN

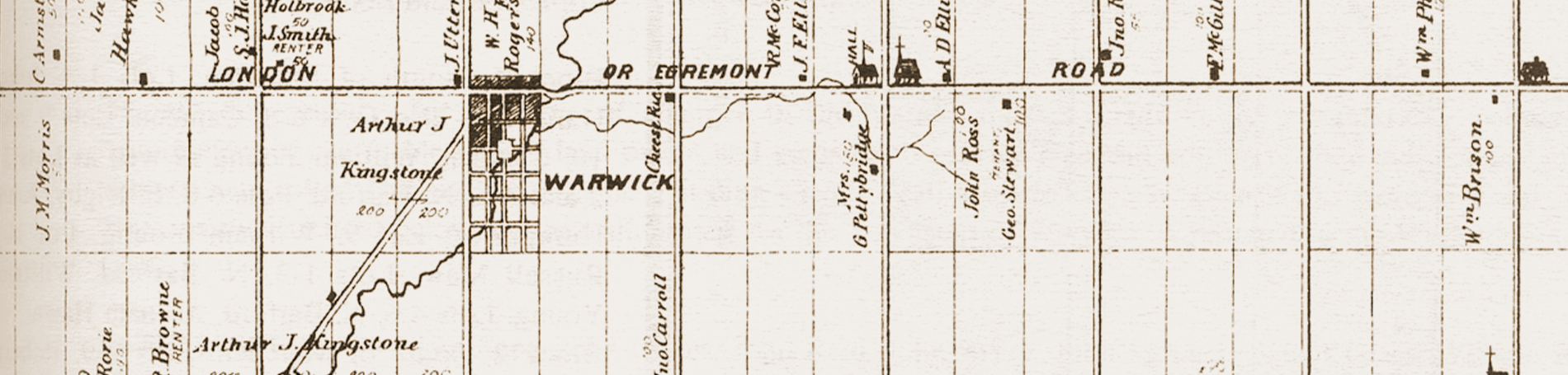

Arthur Kingstone was a successful Irish businessman. Perhaps he had been chanting the popular real estate mantra “location, location, location” when attending a public land auction held in a London, Upper Canada, government office that warm July day. Kingstone had previously examined various parcels of land for sale in Canada West. This day, his focus at the land sale would be on a unique parcel in Township. The land had access to a newly constructed government stagecoach road. Second, due to its southerly latitude, the property enjoyed an attractive climate to support agriculture, benefiting from mild winters and a lengthy growing season. Third, the parcel was located near the growing United States consumer market. Finally, the land was located along flowing water. This businessman had done his homework.

Kingstone purchased 648 ha [1600 acres] in in 1833. Fortunately he possessed a keen eye for land with agricultural potential. He wanted his sons and other hard-working Irish settlers to have the opportunity to achieve economic independence farming land each owned in the “new world” of Upper Canada. Extracts from Kingstone’s diary review clearly the geographic location factors he valued.

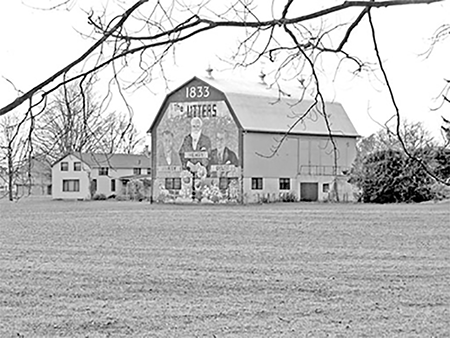

This painted barn near Arkona in northern Warwick Twp. marks the homestead of the Utter family. Courtesy G Pierce.

The requisites I considered necessary for good settlement were – favourable water privileges, favourable climate for crops and favourable locality. The last two, I judged were most likely to be met within the south western townships. The more south, the less continuance of snow [requiring less winter keep for cattle] and less spring frosts, which are destructive to some valuable crops. Besides, it is that part of Canada likely to be called most actively into commercial operation from its propinquity [nearness] to the States.1

While visiting Toronto, Kingstone had interviewed the Canada Land Agent to determine the availability of a large block of desirable land. After consulting the Crown Office, he travelled to the London West area. Here he was introduced to Sir John Colbourne and then Colonel Mount at Delaware (Caradoc). Kingstone’s diary then states

on looking over the map of , found lots 6, 7, 8, 9, on the second concession and lots 5, 6, 7, 8 on the third concession south of the Government road [Egremont] unlocated [not purchased], with a river running through them and a mill seal on it, the lots all around being taken up [already purchased]. The agent informed me that he had refused to set up sale on these lots, keeping them for some person who would undertake to erect a mill on them for the benefit of the township. Consequently, after some deliberation, I attended the public sale at London and was declared the purchaser of the several lots under the conditions that I should build a sawmill on one of the lots.2

Arthur placed his son Charles in charge and returned to Ireland to ready settlers to occupy his property in . Eventually, 25 to 30 Irish families settled on the Kingstone property.3 (The Kingstone property is marked on the map at the end of Chapter 3.)

Records show that some of the early farmers in were Irish but many more were English, including retired British military men who had been honourably discharged and those that were United Empire Loyalists. In 1832 “lot 24, Concession 1 NER was taken up by Lieutenant Samuel Moore as part of 350 acres granted him for service of 31 years with the Seventh Regiment of Foot. He and his family resided on this lot and by 1837, had about 16 acres under cultivation.”4 Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Freear (Freer), a half-pay officer of the British military, was granted land in in 1832 along Bear Creek. Two to three years later he erected an operating sawmill.5 The Freear sawmill “was a godsend to settlers; previously, the nearest mill had been on the Aux Sables.”6 Other early pioneers included William and Sarah Burwell who settled Lot 10, Concession 1 NER on 200 acres [81 ha] in August 1832. This land was granted to Burwell as the son of an Empire Loyalist.7

Civilian settlers of 1832 included the Hume, Thomas, Rees, Donnelly, McKenna, and Hamilton families. In 1833 James Bole and George Lucas settled in the south of while the Harvey, Maidman, Mathews, Liddy, Moore, Randall, Reddick, Robinson and Whelems families formed the “English Settlement”8 in the northwest part of the township.

A famous painted barn located in northern Twp. near Arkona marks the homestead of one of our earliest pioneers. Henry Utter, a descendant of United Empire Loyalist stock, arrived in the area in 1833. His only neighbour was Asa Townsend. Henry occupied the large tract of land that stretched south and east from the intersecting trails of the settlement that is today called Arkona.

Life was full for Henry. Before farming the land, maple, oak, pine, walnut and hickory trees required clearing. In 1843, he built a wood frame cabin. Later, in the 1850s, a brick homestead was constructed and the original cabin was relocated on the property. The Utter homestead is one of the few farms that has remained in the same family since settlement.9

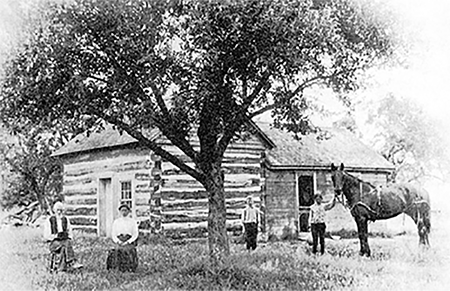

Pioneer farmers in faced immense challenges. First, a shelter had to be erected. Usually this was constructed of logs obtained after felling trees on their land. Archibald Gardner describes early homes in .

Homes in our locality were built of logs; the better ones were hewn, the humbler ones of rough logs. Floors were of split logs, flat side up. Glass windows there were unknown. A little slide was thrown back admitting light when it was not too cold. Doors were of split and hewn logs. Lumber was out of the question.10

Clearing small fields for crops was the next major task. pioneers aimed to clear 2 to 3 hectares (4 to 5 acres) per year. Giant maple, hickory, ash and beech were felled by axe. Oxen were hitched to select logs which were skidded to a storage pile for use in building fences and shelters.

Most logs were assembled in a burn pile. During the first phases of pioneer land clearing and farming, oxen were preferred over horses. A team or “yoke” of oxen was considered stronger, more tractable and more methodical when working among tree stumps and fallen logs. Oxen were also better suited to feeding on natural vegetation including leaves, twigs, weeds and wild grasses. Supplemental feeding of grain was not essential.

The rural custom where many neighbours would gather at one farm to volunteer their help with a specific project was known as a “bee”. Clearing land, raising a barn, cutting firewood would be completed with neighbours’ help and, of course, “many hands made for light work.” Wisbeach area farmer Peter Alison records in his memoir about attending a land clearing bee that “We were at peace and in good fellowship with our neighbours, for the simple reason, we were all paddling in the same canoe as it were.”11

Work bees were a favoured way of dealing with large or monotonous tasks such as clearing land. Source: Dept. of National Defence Library, Archives Canada.

Women had bees for quilting, rug-making or apple-paring and stringing. Bees not only allowed a large work project to be completed more quickly, but were a vital social event, an opportunity to share news and meet other people. Many young men and women met and developed a relationship at apple-paring bees. The men pared the fruit while the young women quartered, cored and strung apples on strings for hanging and drying on cross beams for winter consumption.12

Other common work for early settlers included erecting crude fencing to accommodate two or three cows, calves, three or four sheep and a sow with a litter of pigs. A small collection of ducks, hens and geese likely occupied the barnyard.

Settlement Duties for New Land Owners: The landowner shall thoroughly clear the roadway fronting his lot. Trees are to be cleared and stumps removed two feet from the centre of the road low enough that a wagon wheel can easily pass. Then grass seed is to be sowed on the cleared road. Once the road is cleared, proof must show that a person has constantly resided upon the lot for two years. SOURCE: Susan Utter Hartman’s Henry Utter of Arkona family profile, 2007.

Once the farmer had trees removed from a few hectares, the land could be worked up. A common implement used at this early stage was the A-harrow. “This was constructed of heavy timbers framed in a triangle for convenience in passing between stumps. It had nine or more iron teeth tipped with steel.”13 Using a heavy hoe or axe, holes were punched in the former forest turf, and potatoes, turnips, Indian corn, squash and pumpkin seeds were planted.

Many pioneer farmers in encountered hardship and suffering during the first years. An instance is related where the ox of Sergeant Luckham, an older British soldier, sickened and died, whereupon he and his wife harnessed themselves to the home-made harrows with a harness made from basswood bark, and harrowed in their first crop of wheat. Other cases are reported where settlers nearly starved before getting into a position to raise their own grain. They were obliged to live for weeks on “browse” boiled up as “greens,” and a certain wild vegetable known as “cow cabbage.”14

Established settlers with small numbers of sheep, pigs, calves and a few cows had to remain alert for large predators. Bears and wolves inhabiting stream valleys and forests could inflict serious loss on struggling farms.

Farmers who were able to grow and harvest grain faced another problem. During the early years of , few grist mills existed in the immediate area. As noted earlier, it wasn’t until 1835–1836 that Colonel Freear constructed a grist mill on Bear Creek, but even then it is not clear when this grist mill was ready to operate nor how many months Bear Creek flow rates allowed for its operation. It was 1843 before Thomas Hay constructed his stone flour mill at Village.15 Because the trails were too narrow for wagons or carts, farmers in the northern parts of the township carried bagged grain on their shoulders or across the back of a horse or mule to the Lake Huron shoreline. From this point, a canoe would be used to reach grist mills where grain was ground at Sarnia. Settlers in southern initially transported grain through bush trails to Brooke Mills (Alvinston) or to Strathroy on a primitive road.16

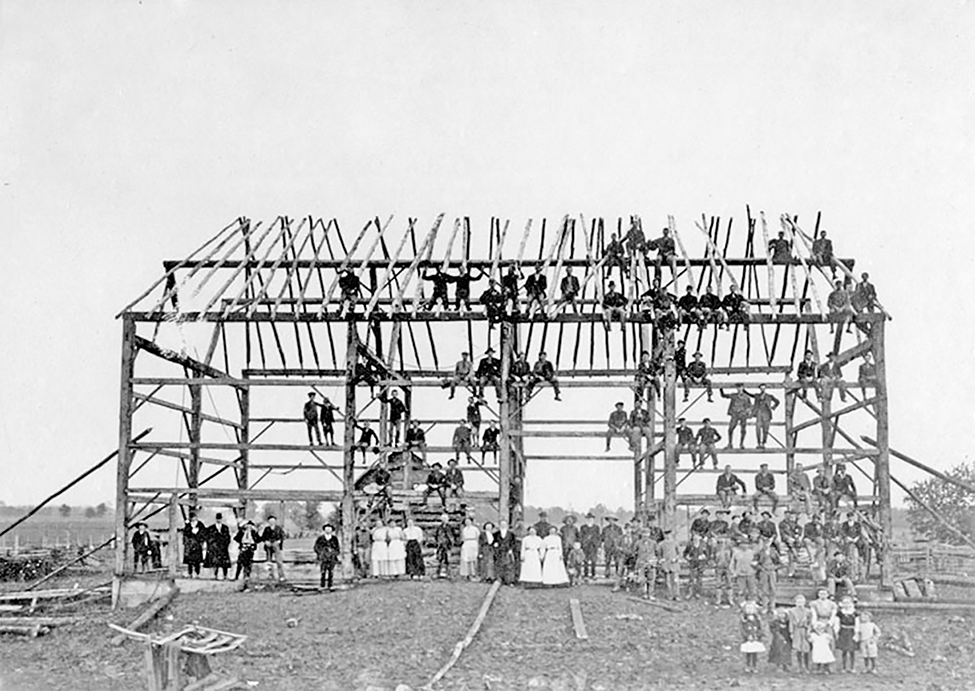

Barn raisings involved the entire community. These work bees were followed by a social time. Courtesy Watford Historical Society.

Barn Raisin’: In July 1908, the Duncan barn was raised. It took 75 to 100 men to raise the barn on an 8 foot wall. Men from 3 to 4 miles came to help. Each bent was 20 feet apart. The first 4 posts were stood up and braced with long 2x4’s. Each bent was added and pinned to the next one with the spur. The inside girts were all mortared into the posts. Wooden mallets were used to drive in the pegs as each was put in place. Every piece was numbered and matched the number on the post. Every stick was hoisted up by hand. Every man had a special job — the brace man, the pin driver. By about 4 to 5 pm, they had the barn all standing. Then they chose sides, one for each end, to put up the rafters. The team that had all rafters in place first were given the right to sample the beer barrel then to rush to the supper tables for a meal well earned. Those taters and meat platters were cleaned off in a hurry. Thick slices of bread and butter and pies of all kinds! We were fortunate to have a beautiful calm day for our “raisin’.” SOURCE: Russell Duncan notes, written 1987, Watford.

Oldtimers had their own methods of having fun and making life a bit more interesting. One pioneer farmer won a very substantial bet by carrying a bag of wheat from Village to Sarnia without taking the bag from his back. The bet was won even though it was found that several stops were made by the winner. However, he did not take the bag from his shoulders, but rested it up against a tree.17

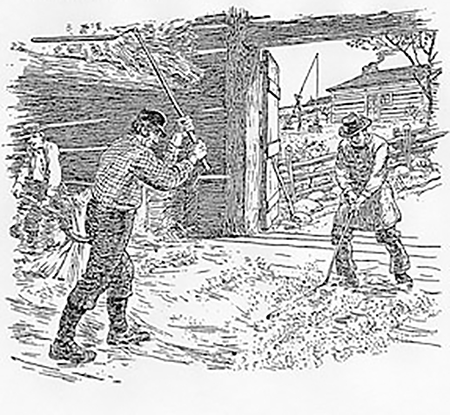

Implements used on the earliest farms in included the wooden plough, the A-harrow, the reaping hook, the scythe and the flail. The memoirs of Peter Alison contain a vivid description of an older man hired to thresh wheat at their farm.

He first made a “flail” — two sticks tied together by their ends. One stick he held in his hands. The other he swung around his head and brought it down with such a thump on the grain that he sent it flying in all directions. He continued this thumping till he had it all thrashed [all straw and grain separated]. Now he had to separate the wheat from the chaff. He chose a windy day and elevating himself upon a stump would pour the grain and chaff out of a basket onto a sheet, and of course the grain being would fall on the sheet, while the chaff blew away.18

Hannah Clark, Lot 28, Concession 3 SER, 100 acres -1851 Agricultural Census: Township Acres under cultivation 18; Acres under crops 15; Acres in woods 82; Acres in wheat 9; Bushels of wheat 80; Acres of peas 2; Bushels 40; Acres of oats 4; Bushels 70; Acres of hay 3; Pounds of wool 15; Pounds of maple syrup 50; Yards of flannel 72; Oxen 2, Cows 1; Heifers 2; Sheep 8; Pigs 3; Pounds of butter 75; Barrels of Pork 2. SOURCE: The Clark Family, Helen Clark, 1990.

farmers in the decade of 1830-1840 were, in the main, self-sufficient. They grew and raised their own food. Their day-to-day clothing was homespun while a straw hat was likely plaited by household members. Archibald Gardner reminds us:

With settlements so far away we had no stores to go to. The clothes we wore came from the backs of the sheep in our own pastures. After being clipped, the wool was cleaned and carded by the women. The nearest carding machines were from thirty to forty miles away. The carded wool was spun into yarn on the spinning wheel and then woven into cloth on hand looms. This cloth, wives and mothers made into clothes for men, women, and children in our own kitchens.19

Flails were used to separate straw from grain. From CW Jefferys’ collection.

Logging and hauling were done by oxen. Grain was cut with a sickle, scythe or cradle and wife and children followed with rakes to bind and stook. Threshing was often done on the barn floor with the cumbersome flail or by the tramping of horses’ feet. Then a farmer would sling a bag of wheat over his only horse or over his own shoulder and stride along a trail to the grist mill where the wheat was ground into flour. The social life of this rural community was largely centred on work bees when neighbours gathered for a logging, barn-raising, road-making, corn- shucking or even a hog-killing. “Women only” bees were held for quilting and rug-making.20

A report by Colonel Roswell Mount of Delaware, dated August 1833, declared that had a population of 852 and a total of 1166 cleared acres (472 ha).21

In spite of obstacles that pioneer farmers in faced, their dogged determination, tenacity and dedication converted forests to fields. Their resolve and perseverance transformed fields to productive farmland. Rudimentary shelters became comfortable homes. Many early settlers captured their vision of freedom, a freedom to benefit from their own hard work and generate the essentials of a fulfilling life.

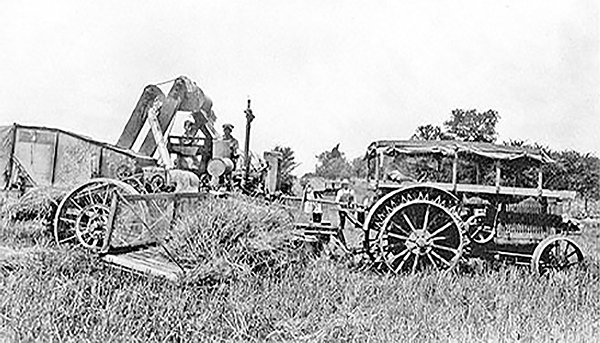

HORSEPOWER, STEAM POWER & WIND STACKERS

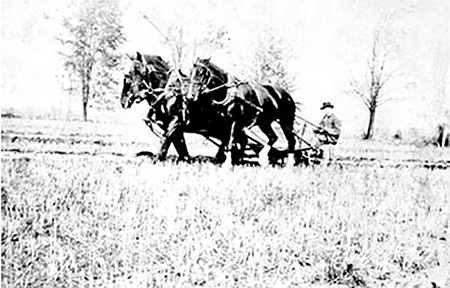

From the 1850s to early 1900, horse-drawn implements replaced many of the farm tasks that previously depended on hand labour and ox. This transition to everyday use of horse-drawn implements also enabled farmers to increase their productivity. New harvesting machines offered some of the greatest benefits. In 1847 Cyrus McCormick marketed a horse-drawn mechanical device called a reaper that cut stalks of grain and deposited them at the side of the machine. This mechanical reaper replaced the manually operated sickle and scythe or cradle. With several labourers assisting, this machine could reap up to 15 acres per day.22

The reaper was soon replaced by a binder that not only cut the stalk but also tied or bound a bundle of grain into a sheaf. Several sheaves were then gathered by hand and grouped into a stook to be dried by the sun.

Seeding was traditionally done with a simple hand- cranked broadcast seeder. Newer seeding techniques were based on quality-engineered grain drills. These horse- drawn drills opened the soil and placed the seed at an ideal depth and spacing.

Firewood was vital to most homes for cooking and winter heat. A frame-mounted circular saw could be driven by a single horse walking in a circle. The horse’s action would turn a central axle that provided power to the saw much like a tractor’s power take off transfers power to machinery today. This “horsepower”-driven saw, with the assistance of four or five good labourers, cut up to 30 cords of wood per day.23 A cord of wood measured 4 feet by 4 feet by 8 feet.

Later, gang ploughs, diamond harrows and heavy cultivators mounted on wheels drawn by a pair of horses were introduced. By the early 1900s, farmers had access to cultivators, wood and steel rollers, seed drills, corn planters, dump rakes, mowers, combined hay rakes and elevators, chain harrows and double mouldboard ploughs.24

This increased mechanization was aided by the development of new steel alloys. During the mid-1850s, bushings for drive shafts were made primarily of hardwood or soft metal. These softer materials required frequent replacement and were a significant source of friction, reducing a machine’s efficiency. Newer steel alloys permitted the creation of very efficient ball bearings essential for the design of more productive machinery.25

Farm life in the late 1800s was surely a very satisfying time for families. A majority of farmers now owned their farms. Substantial houses and barns were common. The scarcity experienced by pioneers had given way to a new level of comfort and abundance. Labour-saving horse-pulled machinery produced a surplus of grain. Roads enabled farm families to attend a church of their choice and visit a wider circle of friends. Instead of rumbling to church or market in an open ox-cart, the farm family travelled in a runabout or carriage pulled by a fine horse. Work bees remained popular, primarily as social events rather than a necessity, although barn raisings and grain threshings still required the combined labour of many hands. Farm women and their daughters had fewer laborious tasks. Mechanization had, in general, freed them from the physical work surrounding hay and grain harvests. Female members of the household were likely responsible for their farm’s poultry flocks and vegetable gardens. Now they were able to extend their interests in church and community organizations. Sewing machines and pianos were found in many farmhouses.

Pioneer farmers often sowed wheat on their recently cleared land. This dependence on wheat as a staple crop continued until the 1880s. Wheat was attractive because there was strong demand and it commanded cash payment whereas most other farm products were items for trade or barter. “The grain was easily transported in bags and its value did not diminish in storage as long as it was kept dry. In most of Upper Canada wheat was far more profitable than other cereals, some of which could not be sold at all.”26

Other significant crops included barley and oats but these, unlike wheat, were for consumption on the farm. Oats were essential as feed for horses while peas were frequently preferred for fattening hogs. However, by the early 1890s a trend developed to devote increased acreage to crops such as hay, corn, oats and clover for forage to support livestock, and less acreage was devoted to growing the traditional grain crops of wheat and barley.27

New rail, road and water transportation was providing access to a broader market. Competition for these markets demanded a high-quality product. To compete successfully in the international marketplace, farmers in and throughout Ontario were urged to become more like industrial entrepreneurs. C. C. James, Ontario’s Deputy Minister of Agriculture, noted in 1895 that productive farmers were somewhat like manufacturers who relied more on scientific knowledge, machinery and business acumen rather than their own physical labour. (By this time organizations such as the Farmers’ Institute had sprung up to teach farmers these principles.) Agriculture is controlled by scientific principles and these principles must be studied.28

Roy Hollingsworth in front of Crystal Palace, Watford. Courtesy D Hollingsworth.

One of the greatest challenges facing farmers throughout time has been the separation of the grain kernel from husk, chaff, leaf and stalk. Flailing and winnowing were utilized by pioneers. One person could produce up to seven bushels per day. By the 1880s, fanning mills in use had hand-cranked mechanisms that could clean over 50 bushels of wheat or more than 100 bushels of oats with one person operating the mill. Larger threshers were designed to be powered by one or two horses on treadmills. Sawyer-Massey engineered a multi-horse threshing sweep which had each horse attached to a bar, causing them to walk in a circle. A gearbox directed power by a rod to the threshing machine.

By 1895, large wheeled threshing machines that handled complete sheaves were manufactured. Sisal twine replaced the wire ties that horse-drawn binders had employed for bundling sheaves ready for stooking. Self-feeders were now attached to the front of the machines along with a governing mechanism to prevent sheaves from jamming the threshing cylinder.

Removing straw and chaff was further mechanized by the introduction of a “wind stacker”. A large fan mounted at the rear of the machine provided the force for blowing chopped straw out a large galvanized metal tube into a pile. The tube could be raised and rotated, thus offering more flexibility in terms of the size and location of straw stacks.

Due to the increased threshing capacity of these machines, it was no longer feasible to manually bag grain. Instead, an enclosed bucket elevator carried grain directly from the pan into a wagon positioned beside the threshing machine. By the turn of the century, most elevators were equipped with bushel counters that automatically measured the grain as it was fed into the wagon. Manufacturers could now safely claim their machines offered a threshing capacity of more than 1,000 bushels per day — a figure easily doubled by some of the largest machines.29

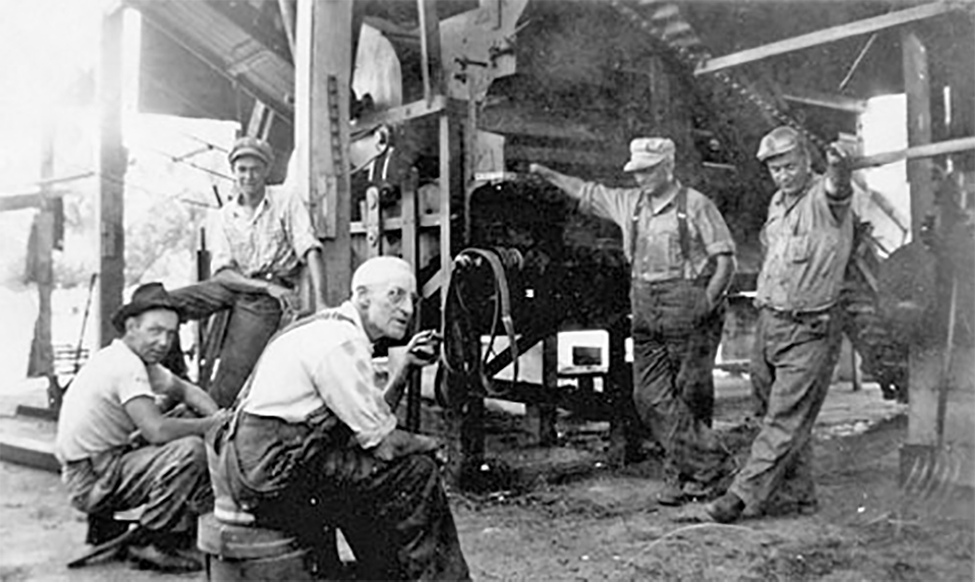

Operating a team of draft horses around the mechanical clatter of a running thresher demanded a capable driver and well-trained animals. Jack Aitken recalls the special demands of the first threshing of the harvest.

I always remember the first threshing. The threshing machine would be running and you had to put the team right up beside the separator. The horses had to stay there while you unloaded. And everything was running crazy and the belts running right beside them. At the first threshing or two, everybody’s horses would be goofy. And then they’d get used to it. Uncle Dick’s team was one of the more patient ones. Tantons’ weren’t that patient. They were scared skinny. He would shut the threshing machine down so that the separator wasn’t running and he would lead them up and he would pet them, hold them while you started to pitch off and after 2 or 3 times they’d walk up there and it got so that they’d pretty near walk over the thing. They didn’t mind at all. That was something you had to get used to. Every horse was different.30

Photos of grain threshing frequently include many workers surrounding the thresher and the steam-powered traction engine. It was normal for larger machines to require at least the following labour:

- 3-4 men to load stooked sheaves onto horse-drawn wagons

- 2-4 men to drive the teams bringing wagons filled with sheaves to the threshing machine and unload sheaves into the self-feeder

- 2 men to maintain and operate the steam traction engine fire box and belts

- 1 man to tend the wagon that the threshing machine was filling with grain

- 1 man to oversee the threshing machine operation

In spite of increased mechanization, the threshing process remained labour intensive. The combined cost of a steam traction engine and threshing machine was prohibitive for the average farm, resulting in custom or contract threshers being hired. Lew McGregor notes in his memoirs:

There were only a few threshing machines in the area. They passed through the neighbourhood from farm to farm. Each area had its own work section consisting of the farmers in a two mile stretch which amounted to about 18 farms. These groups worked to help each other. They were notified of the need for help by a long ring on the party line [telephone]. One long ring and everyone picked up the phone to find what was needed. Threshing was hard work.31

Florence (McRorie) Main writes in her memories of threshing as a colourful event.

When the grain had been cut and was dry enough to thresh, Mr. Les McKay moved in with his steam engine pulling the threshing machine and water tank. The thresher was backed into the barn with the grain coming out the pipe into bins and a long pipe carrying the straw to make a stack in the barnyard. The cows loved to brush against the fresh straw. Wide belts ran from the engine to the thresher. One of the children was sent to tell Mr. McKay when dinner was ready. He’d give 2 or 3 blasts on the whistle and all the crew came out, washed the worst dust off in a wash tub of warm water with soap and towels and went into the house to enjoy a feast-like meal.32

Annual Farm Wages in 1928–29: Married male $400; Single male $330; Boy $316; Woman $316. SOURCE: W. P. Macdonald, Agricultural Field Representative, Annual Report of Dept. of Agriculture covering Twp.

In 1904 J. I. Case of Wisconsin marketed the first all- metal thresher utilizing an angle-iron frame and metal panels. Case anticipated using metal would offer greater structural integrity than wood-framed machines.

Despite manufacturers’ assurances that their machines were made with the finest kiln-dried hardwood, and that a regular tightening of bolts would suffice, a threshing machine operating at full speed would have been subject to incredible strain. Although manufacturers of wooden machines initially scoffed at J.I. Case’s product, many — including the George White Company of London Ontario (680634) — followed suit and switched to the production of metal machines.

Threshing machines had finally reached the pinnacle of their technological evolution. Rubber tires might replace wooden wheels, and grease cups would be supplanted by compression grease fittings, but the internal mechanism would remain unaltered.33

Warwick IN TRANSITION

There’s something elemental about watching a man and a perfectly-matched pair of mules or a double team of red-roan Belgians work like a synchronized and finely-tuned machine […] the dull plod of great hooves on mellow earth, the jingle of harness, the sigh of a shiny moldboard slicing a strip of sod, the gentle urgings of the driver, the barely audible straining of the team.34

Some have said that “a farmer’s best friend is his horse.” Ploughing, harrowing and harvesting with the help of a living creature can generate a mystic bond, a unique working partnership valued by many farmers. Whether working fields or driving to town for supplies, most farm families took great pride in their horses. Certain horsemen would argue that the relationship between owner and horse was mutually satisfying. Working horses served many farms faithfully and productively for more than a fifty-year period in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A team of draft animals required a limited capital investment and was ideal for working the small, irregularly-shaped fields so characteristic of mixed farms. The horse was king until the 1930s.

To successfully bring together an implement and a draft animal required the skill and knowledge of a first- rate horseman. Horsemen had to possess an innate feeling for their animals, commonly termed “horse sense,” to deal with training, feeding, grooming and health care. Being able to identify and treat ailments such as mud fever, founder, glanders, colic and greasy heel was an asset. Farmers knew horse names should be short: names like Tom, King, Molly, Diamond and Queen permitted clear instruction and lively interaction.

Another aspect associated with horse-drawn vehicles and implements was the breeding of good horses. Horses were used everywhere, not only for drawing light carriages such as buggies, cutters and democrats but also for heavier conditions where a draft animal was a necessity. A common occupation was providing stallion services. The owner the stallion advertised the virtues, specifications and the scheduled location in local papers.

Utility was not the only requisite. A surrey with a fringe on top was a major asset for a young blade setting out to “wow” the fair sex. Along with a fine rig went a good-looking strutter. Pictures from that era prove how handsome the setup could be and the obvious pride in its possession. (This translates as “a fine looking horse and carriage was an asset to a young man going to meet his girl friend.")

Stewart Smith owned two stallions at different times. His first successful sire was Clellan Chief, followed by a trotter named Moneo. The business plan was

that [horse] owners could breed their driver mares and have replacements coming on for the future. In those days, you couldn’t go out and buy a new car as you do today. If a new “driver” was needed and you hadn’t a horse coming on to fill the bill, you had to scour the countryside to see what was available in young drivers….

The farmer needing a more versatile kind of animal could breed his heavy draft mares to this trotter. The crossing produced a more general purpose foal which was very tough and wirey and, when broken in, could be hitched to the buggy as a driver or harnessed up and hitched to a plough, wagon or as a third horse on a 3 horse hitch. This type of horse was very saleable, large enough to be a work horse yet agile enough to be a driver… [as] large breeds were unsuitable for this purpose.

Stallion owners and handlers had a route with stop-overs at different intervals.… The Stallion was available at the home barn as well when not travelling. I remember seeing a poster for Clellan Chief displaying a picture of the horse and information as to pedigree, routes, locations and times.35

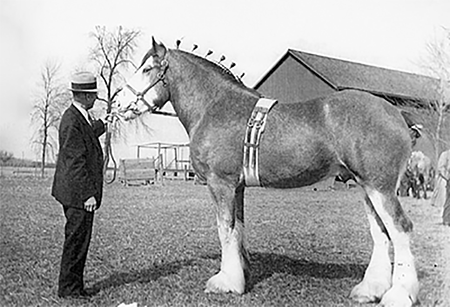

An internationally-renowned Twp. family business owned by the Brandon Brothers helped provide horsepower to farmers, logging camps, large businesses, prison farms and the show circuit. James, William and Robert Brandon of Birnam Line, sensing an increasing need for more top-quality draft horses, decided to establish their own Clydesdale breeding program. After the purchase of a number of first-rate purebred mares and securing one of Canada’s top Clydesdale sires, Gallant Baron, their breeding program was underway. As business grew, the Brandons began to import the best stallions and mares they could locate in Scotland.

Farmers that purchased mares from the Brandons would return their mares to be bred by one of the Brandons’ quality stallions. Their business plan was paying off. The general quality of Clydesdale horses on farms was improving. Many farmers began to show at local and national levels, where their winnings would of course reflect well on the Brandons. Also, farmers could sell their colts through Brandon-organized sales. All parties were pleased.

In February, 1920, the Brandons imported the stallion Carbrook Buchlyvie, who had sired numerous outstanding colts in Scotland and North America. Carbrook and the stallion Forest Favourite helped solidify the Brandons’ reputation as one of the leading breeders in the world. Carbrook was ranked first at the Royal Winter Fair from 1922 through 1938 while Forest Favourite won at the prestigious International Stock Show in Chicago in 1922. The Anheuser- Busch brewing company of St. Louis, Missouri, secured ten horses from the Brandons between 1933 and 1948 and these became their trademark. On April 12, 1948, the firm of Brandon Bros. came to an end with the death of James on the farm his grandfather first occupied nearly a centuryearlier.36

In the same way that the car and all associated industries seem to govern community life in 2008, so the horse dominated life in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Business was assured for any blacksmith, wheelwright or harness maker who cared to set up shop. The veterinarian ranked as high as the doctor. Many merchants owned a wagon or van and at least a couple of horses.37

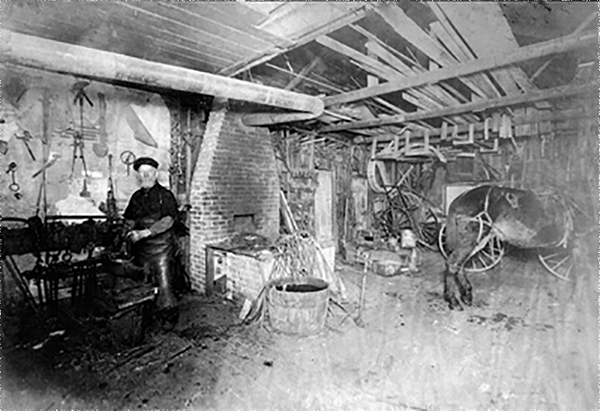

Joshua Saunders’ blacksmith shop, Watford. Courtesy D Hollingsworth.

Warwick had a number of blacksmiths, carriage makers and farriers. The former Birnam blacksmith shop at the intersection of Nauvoo Rd. and Birnam Line remains a well-known landmark where Ammon Rogers and Billie Beach worked. Ethel Smith recalls the names of men that looked after the horses of .

Mostly all travel was done by horseback. Stage horses also needed attention. William Robertson had a blacksmith shop and men named Cable, George Stilwell and Alfred Cox worked this area. John Humphries [of Village] was an expert carriage and wagon maker employing eight men in his shop. Spokes were shipped in billets so each was shaped and fitted by hand. Leather for seats and dashboards as well as flannel topping for vehicle tops was shipped in large rolls. Mr. Humphries personally made buggy tops and seats, stuffing the seats with seaweed and horse hair. All units were hand sewn. His products were sturdy and easy to drive. Winter cutters were also produced by Mr. Humphries until retirement in 1912. Alfred Cox continued with iron work and shoeing horses until 1937. Russell Ward carried on with the work until 1941.38

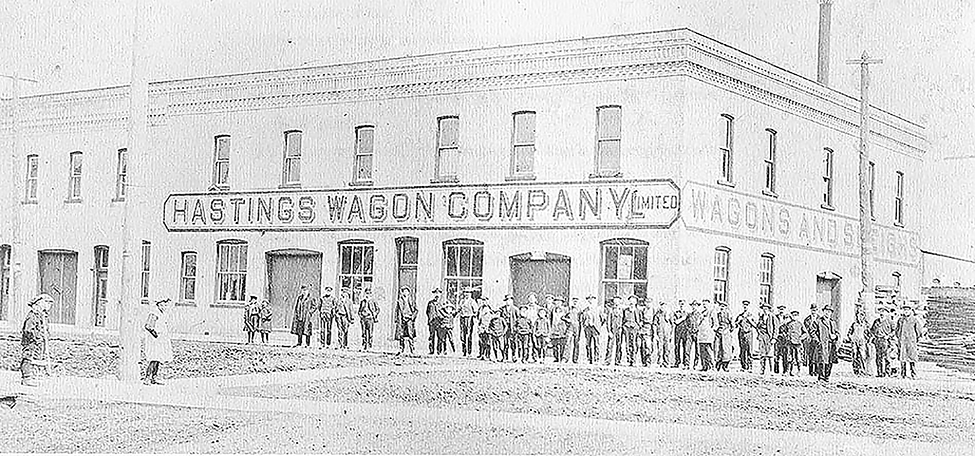

Hastings Wagon Co., corner of Main and Huron St., Watford. Courtesy G Richardson.

In Watford, several blacksmiths did a flourishing business. John Lovell was south of the bridge where he shod horses and also made buggies and wagons. East of Watford Inn, Angus Mitchell offered blacksmith and buggy fabrication services. Isaac Hastings & Co. made sleighs and wagons on the east side of Main St. between Huron and Ontario St.

Dave Maxwell worked at blacksmithing and made a car now in the Watford museum. The present post office building is on the site of the Bambridge blacksmith shop. Livery stables where horses and buggies were kept for hire were owned by J. Bambridge, W. Cameron, Restorick and R. Auld.39

This memoir by Ella (Anderson) Atkins offers a glimpse of rural life and how equines were a valued and trusted part of daily routines about 1900.

One Christmas my uncle Will Sullivan (mother’s brother), his wife and family came to our house in a big sleigh all covered up with straw and blankets with a pony, named Fanny, tied behind! She was a fine sturdy Indian pony. My uncle said, “Fanny is your Christmas present and if you are good to her, feed her lots of carrots and apples, in the spring she will bring you a little colt.” Never did we have a lovelier Christmas present. Fanny got all kinds of special treats. Sure enough on May 24th, Fanny brought us a beautiful black colt with a white star between his eyes. There was great rejoicing and it was a school holiday. We named him Prince. We wanted to name him Victoria after our beloved Queen, but being a male colt, father advised us Prince would be better. So the 24th of May has always been “Prince’s day” in our family. The next day we drove Fanny with the cart and our beautiful colt ran beside her. He got tired when we reached Dan Thompson’s and lay down. So we ran in to tell Henrietta to come and see our beautiful colt. After a while, Prince got up and we went on to school. The Anderson children were proud that day. A colt had never gone to school at SS No. 5. There was a church there and a shed. So Fanny and her son lay down and rested in the shed. From that day on Prince went to school. When we went to Watford High School, Prince took us in the cart. He was a knowing horse. We used to sing and he would put his head down and pace. Few horses ever passed our dear old Prince. When Ethel and Bert (my sister and brother) finished high school, they attended Model School [a school where prospective students learned to be elementary school teachers] in Forest. Again Prince took them to Forest on Sunday night. They boarded in Forest (Prince too) until Friday night when they came home. Ethel taught school at Bethel. Again she drove Prince back and forth. In winter, she boarded with dear old people named Joseph and Barbara Crone. So you see Prince took us everywhere and was such a part of life.40

Pesky summertime flies are a nuisance to horses and cattle. Flies bite around the nose and mouth causing animals pain and discomfort. Individual farmers had designed burlap bags to fit over muzzles but the burlap proved to be too warm and no doubt uncomfortable. Around 1914, a Watford company, Andrews Wire Works (later Androck Company Ltd.), designed a “nose guard” made of wire cloth which was comfortable for animals to wear and effective for deterring flies. This “nose guard” was a very successful sales item which sold over 500,000 units in peak years.41

One of the more celebrated horses based in the area was from the racing stable owned by Thomas Roche, a noted horse breeder and fancier. Roche owned numerous horses in his time but the most famous was the trotter Paddy R.

As a colt, he suffered a broken leg but through good veterinary work on the part of Roche’s crony, Dr. McGillicuddy, Paddy R was nursed back to become one of the greatest trotters of his time. Paddy R was the hero of an episode still recalled by horsemen. A Port Huron breeder challenged Roche to a race. Roche accepted. Paddy R was driven to Sarnia and proceeded to cross by ferry. The ferry became wedged in the heavy ice. Nothing daunted Roche. He had his horse and cutter unloaded and with thousands of people watching from both banks, completed his journey on the floe ice itself. Despite the ghastly experience, Paddy R won the race and a $500 bet — a sizeable sum of money at that time. Paddy R and Red Rose, another outstanding Roche horse, won many a race.42

During the 1900s, farmers had three sources of power: their own muscle strength, draft horses and steam power. Steam engines were mainly utilized for stationary operations such as threshing, filling silos and for powering corn cutter boxes. Due to a steam tractor’s 20,000 to 30,000 pound weight, they were not suited for work on damp ground. Operators were humiliated when mired machines required rescue by draft horses. Due to their weight, mechanical complexity and cost, steam- powered units did not displace the farm horse.

One of the most visible components of modern farming is the ubiquitous farm tractor. Developed during the first half of the 20th century, it altered the fundamental nature of agriculture and changed key components of daily life in rural Ontario. Hindsight would suggest that by applying the internal combustion engine to the tractor (along with the auto and truck) rural North America was changed forever, both economically and socially.

During the early 1900s, the internal combustion engine was refined and commercialized. Farmers quickly adapted small stationary gasoline engines to tasks such as pumping water. Innovators applied the stationary gasoline engine to a mobile unit called a “tractor.” Initially, gasoline- powered tractors were similar to steam engine tractors with immense steel wheels, enormous weight and high cost. Soon, tractor designers reduced the weight of tractors to 2,000 to 6,000 pounds, with pricing around $1,000. Henry Ford produced an inexpensive unit during World War I when horses were in short supply due to the military demand. During the 1920s Ford and International were selling small farm tractors for $400 to $800.

Power take off was introduced in 1922. PTO describes the use of a metal shaft turned by a tractor’s motor which permits implements to be driven by the tractor engine rather than a wheel rolling over the ground. Implement manufacturers began re-engineering equipment lines to match this important development. Other significant innovations by tractor manufacturers included the adoption of a power lift in 1927, which allowed the tractor operator to raise or lower heavy ploughs and discs by simply moving a hydraulic lever on the tractor. This led to larger tillage equipment.

Queenie Edwards driving McCormick-Deering tractor and combine, 1927–1928: Note the person bagging the grain. Courtesy L Koolen.

By 1938, rubber tires were replacing steel wheels. The low-pressure tires reduced soil compaction and permitted faster ground speed due to decreased friction. The development of diesel engines in the mid-1930s gave farmers access to a lower cost fuel for their machines. Many tractors from that time forward had a small gasoline tank for cold starts, and a large diesel tank for the majority of the operation. By 1937, Ford-Ferguson tractors introduced the by now perfected “three-point hitch,” a device that produced superior ploughing by continuously levelling the implement as it travelled over uneven fields. The three- point hitch design was quickly imitated and introduced by other manufacturers.

The self-propelled combine was introduced in 1937– 38. Since it required only a few people for operation, compared to the teams of men assembled during threshing, this development

freed a tractor or horses and human labour for other work, opened the field without running down the crop, moved at speeds up to 4 mph [miles per hour] and reaped, and threshed and delivered a stream of grain from its delivery spout in a single continuous automatic operation. Whereas, it once took a man 40 hours to reap and flail a bushel, it now took one man less than a minute.43

Ron Ellerker with corn binder, 1963. Courtesy W Dunlop.

Farms at this time were generally classified as “mixed” operations. Typically farms had numerous types of livestock, poultry and grew crops to support them. Many farms had a bush lot for firewood and possibly maple syrup. Often some acreage would be devoted to a cash crop. In her memoir Jean Janes, daughter of Elsie and George Janes, of Brickyard Line, reviews the seasonal rhythms that characterized numerous mixed farms of .

In the early spring, George and Elsie would go by horse and buggy for the day to the sugar bush. Lunch was heated either on the wood fire or on the pans of syrup. George had tapped the maples and was now able to gather sap, which had accumulated in pails, and poured it into a large round metal container drawn on a stone boat by his team of horses. He had raised this team from a cross of a draft horse and a light, western-coloured horse so that, although draft horse in stature, they were light tan with black manes and tails. They were gentle and obedient and George was very proud of them. During the war of 1939-1945, maple syrup was a great commodity when sugar was rationed.

Examples of Farm Prices, 1914–1932:

| November 1915: |

wheat sold for $1.40 a bushel; oats for |

| November 1916: | pigs sold for 11 cents per pound |

| March 1919: | maple syrup sold for $2 per gallon |

| July 1919: | cattle sold for 10.3 cents per pound |

| April 1920: | a dozen eggs sold for 43 cents |

| September 1920: | chickens sold at 42 cents per pound |

| November 1920: | 2 sheep sold for 5 cents per pound |

| November 1920: | 4 pigs sold for 14.5 cents per pound |

| February 1932: | hogs sold for 4.5 cents a pound |

| February 1932: |

oats sold at 20 cents per bushel; wheat |

| April 1932: | paid Dr. Howden $1 for pulling a tooth |

| June 1932: |

purchased 15 boxes of strawberries for |

| December 1932: | eggs sold at 16 cents per dozen; butter 18 cents per pound; wheat 40 cents per bushel; oats at 20 cents |

| December 1932: | purchased a loaf of bread for 15 cents |

SOURCE: diaries of Stephen Morris and Russell Duncan

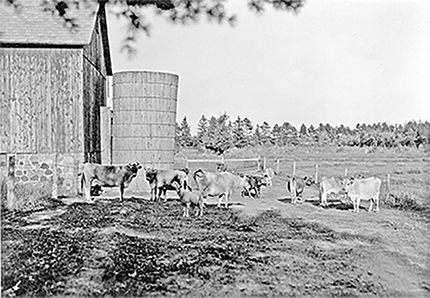

As spring temperatures warmed and grass grew, cattle that had been confined to the barn all winter were let out to pasture. This was a sight that warmed the heart – to see them free as they kicked up heels with delight. Cattle required fences and all the small fields were fenced to alternate crops with grazing fields. Generally a bull named Bill was kept.

As spring advanced and soil warmed, crops of wheat, oats, malting barley, turnips, canning-factory peas and corn were planted. There was also an acre or two of potatoes, which they used for themselves. Any extra potatoes were sold to George’s brother, Ray, who owned a grocery store in Sarnia. During the war years, rationing was placed on sugar, butter, coffee, tea and meat. The effect of this was minimal on the family because of the farm. There were always enough hogs to pay the taxes and if there were extra, they were sold to Ray for his Sarnia store.

June was haying month. Hay was cut with a mower, moved into a windrow with a dump rake to help the hay dry thoroughly. Then a hay loader was attached to the wagon and, as the horses pulled the wagon, the hay was dumped down from the high hay loader onto the wagon which, when loaded, was taken into the barn loft. The horses were guided back outside and hitched to a rope attached to the hayfork which speared a large part of the loose hay and, as the horses pulled, the hay rose up and across the barn on a track to where it was dumped and then spread around the mow by hand-held hay forks.

After haying, peas were harvested. One year, the sweetness of the peas prompted two children to plan getting up very early, before the household had stirred, to go and eat peas! Unfortunately, Elsie had good hearing and the plan was abruptly aborted.

Usually there were about twelve cows milked twice a day. This meant that when Ray Janes, George’s brother, invited the family to his cottage at Bright’s Grove, the family had to leave after supper to milk cows. Cream was sold to the Forest Creamery. When the creamery picked up cream for the farm, it left the pounds of butter Elsie had ordered.

Elsie always had a large vegetable garden to be tended. As well, fruits were to be canned during the summer. Then in the autumn, items such as chili sauces, pickled beets etc. were canned. Flower gardens were also important. Neighbours exchanged roots at various group meetings.

July brought oat and wheat harvests for which a binder was used. First, horses were used for power and later, a tractor. The binder cut and gathered so much of the wheat stocks together and wrapped binder twine around them, dumping the sheaf on the field. Stooking required several people. Some years a farmer from the west was hired to help with the harvest through the government-sponsored program called “farm excursion”.

Within the month, a custom farmer came with a threshing machine and a ‘bee’ was held by neighbours to thresh grain from the sheaves. Grain was stored in a granary in the barn. When threshing was finished, a beautiful, large pile of yellow straw attracted playful children.

August and September probably involved ploughing so fall wheat could be planted. Ploughing might continue on, as time and weather permitted, even into January. When it became cold in October or November, a pig was slaughtered and butchered for family use by George. Saltpetre [potassium nitrate] was applied by Elsie to preserve the pork. Fat was poured over the pork in crocks in earlier years. Later it was stored in the Woods’ cold storage in Watford.

Winter was a busy time attending to cattle, hogs and horses in the barn. Clean out was made somewhat easier when a litter carrier was acquired. It ran on tracks to the barn exterior. A milking machine (DeLaval) also added an improvement. Milk pails were quite heavy if two cows’ milk went into them….

For many years grain to be milled for cattle had to be taken to the mill in a trailer towed by the car. Later a milling machine was purchased to do the work at home. There was wood to be cut in the bush to fuel the in-house furnace and for maple syrup production. There were potatoes needing to be sorted as well.

Occasionally heavy winter storms made the roads impassable as the township did not run snow ploughs. However, farms still had sleighs and horses so, if there was an emergency, the high drifts could be overcome.

Chickens were always kept. Eggs were sold to the grading station in Watford. Elsie cleaned eggs in the evening…. It was always a curiosity to see hens up in [the] willows by the creek laying their eggs in summer.

Through time, more conveniences were acquired and a truck was purchased. George was keen to learn of new farming techniques and plants. For many years he sold fertilizer in and Brooke Townships. At that time, it arrived on trucks in solid granular form. George truly loved farming and his animals. He could not entertain leaving the farm. In fact he was reluctant to leave the farm for more than a day, even in retirement.44

Young Men and Women Ontario Farmers are Calling YOU NOW! So desperate is Europe’s need for food … so urgent our farmers’ need for help that this Province is facing the most serious farm-labour shortage in its history. 1946 is a crucial year — and every one who can, should help. Young Ontario citizens are urged to pitch-in and play a worthy part in feeding the starving nations of the world. “LEND A HAND” You — and thousands of others like you — are needed on every type of farm. The peak season runs from April 12th to October 15th. Pay is good. Clean supervised accommodation. Good food. Here is your opportunity — among pleasant companions — to enjoy a profi table, healthy summer. Join the Ontario Farm Service Force — today ! Fill in the coupon marked out below. A Registration Form, plus all particulars, will be sent to you without delay. DOMINION-PROVINCIAL COMMITTEE ON FARM LABOUR AGRICULTURE – LABOUR – EDUCATION SOURCE: Watford Guide-Advocate, April 26, 1946.

As the mechanized world was embraced by farmers, it became evident that the working horse, the support services, and industry around it were doomed. Farmers quickly calculated the benefit of a tractor on the farm. Tractors were ploughing 20 acres per day while a good draft team only managed three to four acres. Tractors were able to complete field or crop work at the optimum time. Only one man was required to do field work and fewer men were needed when harvesting with a combine. Tractors are simply turned on and off and then parked. Crop and grazing acreage designated for pasturing or growing feed for horses could be used to support crop production. G. Elmore Reaman calculated that “each tractor from 1931 to 1961 in Ontario replaced approximately four horses. This, in turn, released for crop production for purposes other than growing grain and providing pasture for horses, approximately 3.5 to 4 acres per horse or nearly 15 acres per tractor.”45

Horse prices soon sagged, and, because there were fewer buyers, dealer numbers declined. Breeding operations suffered. As time passed, equipment manufacturers ceased producing implements for horses, and the need for fewer horses impacted the demand for blacksmiths, harness makers and carriage builders.

Boere corn crib. Courtesy G Boere.

Isolation, in varying degrees, was a fact of life for most people of in the early 1900s due to distance or limited transportation. Mail might be collected once a week if the farmer could get to the local post office, where he might also hear the latest news. However, between 1900 and 1960, rural living changed dramatically.

The impact of the tractor has been noted, but other change agents included the auto, telephone, electricity, rural mail delivery, moving pictures and radio broadcasting. When daily rural mail delivery was instituted in 1908, a farm family could subscribe more easily to a daily newspaper and learn about provincial, national and global affairs. The telephone encouraged ongoing community contact. Improved roads made more distant travel by auto feasible. Listening to radio reduced farm family isolation and helped listeners acquire an increased understanding of agricultural affairs. Many farms participated in the popular “Farm Forums” on national radio. (See chapter 19.)

Ernest Albert Edwards combine and covered steel wheel tractor, 1938. Courtesy L Koolen.

The auto soon enabled people to travel to movies, which exposed them to different places, fashion, music and values. Gas or diesel-powered machinery such as the combine provided farm people with more leisure time. Farm women, for example, were no longer expected to provide enormous meals for hungry threshing crews.

The increasing popularity of the tractor on farms was gradual, just as was the decline in the number of farm horses. Both trends were steady and the outcome certain. Census data lists ’s horse population in the year 1931 at 1863 animals. By the census year of 1961 the horse population was 173. On the other hand, tractor units in totalled 586 units by the year 1961.46

Interestingly, there was an extensive transition period between 1900 and 1930 in which farms saw all power types in use, including steam engine, draft horse and gas or diesel tractor. Initially, the steam or gas units supplemented the farm horse but eventually farmers increased their dependence on the internal combustion tractor, some more quickly than others.

Lambton Federation of Agriculture: After experiencing the Depression and World War II’s rationing, most farmers in and Lambton recognized the need for a strong united voice to address their common concerns. The Lambton Farmers Association (later changed to the Lambton Federation of Agriculture or LFA) was a grass-roots organization created in 1941. Two directors from each township were appointed. Kenneth Janes and Swanton Reycraft were the first representatives. “Buying clubs,” later known as “co-operatives,” were early economic structures that pooled member buying power for seed, coal, fertilizer and flour. At meetings in 1947 through to the early 1950s, the Federation actively supported the introduction of co-operative life, automobile and medical insurance, offering Lambton farm families their first affordable hospital and surgical insurance plans. Rural issues addressed over the years included member funding, embargos on export cattle, farm hydro rates, marketing campaigns, improved rural assessment, operating loan interest rates, land expropriation due to the Hwy 402 expansion, confusion over metric labelling on chemicals, debt review, price stabilization, nutrient management, landfills, competing with European Union and USA price supports and fair prices for crops and livestock. The Lambton Federation of Agriculture remains active in fulfilling its mission statement: “to be an advocate for agricultural producers through networking, education and communications with community and governments.” Presidents of the LFA from over the years have been: Ken Janes (1945), George McCormick (1949), Wm. Blain (1960–61), Howard Huctwith (1970), Mac Parker (1985–86) and Dennis Bryson (2004–05). In 2008 the Secretary-Treasurer is Brenda Miner. SOURCE: Brenda Miner, 2007.

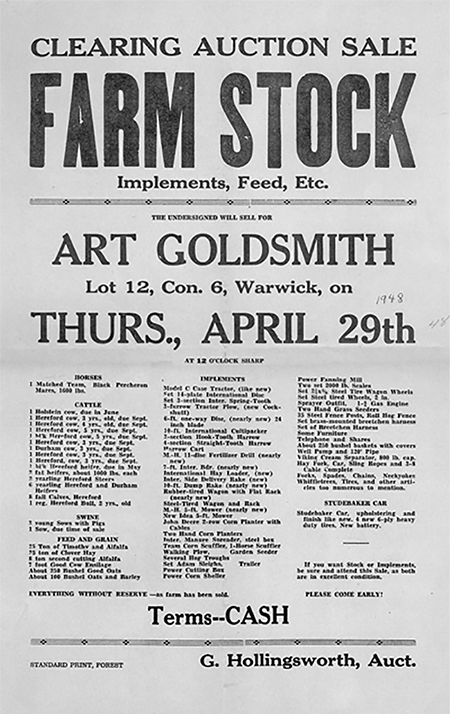

Auction sale advertisement, 1948. Courtesy M Rutten.

Different farming tasks demanded hard work but amusing banter, kidding and good fun helped the day move on. George Holbrook of Egremont Rd. remembered a day of working with a steam engine owned by Jack Harper at Joe McCormick’s farm on Brickyard Line. The steam engine was being used to fill a tower silo with chopped corn. George told the story of the boiler crew deciding to play a joke on Joe. Joe McCormick ran a tidy farm and always kept everything in place. But a steam engine boiler demanded a continuous supply of wood to keep running and it was always the host farmer that was responsible for providing the fuel. Joe had assembled a pile of scrap lumber, broken fence posts and some sawn firewood to be used in the boiler. He also had a pile of fresh cedar fence posts stacked carefully beside the barn. While farmer Joe was out of sight, inside the open top silo tramping down corn, a group of fellows loaded all the new posts but one onto a flat rack wagon and towed it behind the barn where it was parked out of sight. One of the workers then climbed the silo and spoke to Joe, who was still tramping corn, and had no idea of what was happening at ground level. “Joe, did you want all those posts to go into the boiler?"

Well, Joe was out of the silo down to ground level like lightning! He was truly steamed. When he saw the boiler crew standing beside the boiler with what appeared to be the last remaining new fence post from the pile, he was furious. He then proceeded to give Jack a verbal lashing, wondering how a crew could be that brainless, burning all those perfectly good posts! Only after the work crew stopped laughing and the loaded wagon returned from behind the barn did Joe discover the truth. He had been completely set up by his work friends!

Although diesel tractors are the dominant power used by farmers today, horses remain part of the rural landscape. Often they are the focus of recreation or a hobby. Certain farms have identified the horse as a business opportunity offering boarding, riding and breeding services. The most recent Census of Agriculture recorded 99 horses and ponies on 16 farms in in 2006.

Lambton Cattlemen: This grassroots organization, established in 1958, strives “to promote improvement in the quality of beef cattle produced in Lambton County”. The executive has done this by providing industry-related information to members, lobbying governments and tracking issues specifi c to the beef industry. Some issues addressed by the Cattlemen since 1958 include supply management, farm fi nancing, tagging for universal identifi cation and trace back capabilities, Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE), export closures, Clean Water Protection Act and age-verifi ed cattle. Over the years, Lambton Cattlemen have actively participated in Cattle Feeding and Marketing Short Courses, Herd Health workshops, Red Meat Program and farm tours throughout Ontario, western Canada and the United States. Lambton Cattlemen sponsor Agriculture in the Classroom and 4-H. They hold an annual Beef BBQ, attended by over one thousand people in 2007. farmers that have served on the Lambton Cattlemen’s executive include: President: Ken Janes (1962), Bruce Miner (1986) Directors: Howard Cameron, Howard Huctwith, Ken Janes, Bruce Miner, Lee Miner, Ralph Miner, Clare Moffatt, Lloyd Moffatt, Lyle Moffatt, John O’Neil, Mac Parker, Murray Spalding and Allan Roder Secretary: Brenda Miner SOURCE: Brenda Miner, 2007.

The period of transition from the early 1900s to 1960s introduced substantial change to farms. Most farmers saw these changes as opportunity and adjusted through time. Looking back over this period reminds us that these changes impacted many facets of rural life. The mechanization of farm operations involved a transition from horse to tractor, from binders and threshers to combines, from extensive use of farm labour to a greater dependence on electricity and machinery and from modest to greater capital investment. The auto broadened community from one that was local to regional and increased choice and variety of experience immensely. Although magazines such as the Farmer’s Advocate, and even local papers, were common as early as the 1870s, the introduction of daily mail, daily newspapers and radio broadened sources of information from local to regional, national and global.

Auction sales remain a part of farm life. Courtesy M Ford.

BEEF RINGS & PEA VINERS

Memoirs, diaries and photos submitted to the Township History Committee by families provide a glimpse of rural life during this period of transition. Daily routines, barnyard peculiarities, childhood duties, specialized crops, amusing incidents, labour rates and labour excursions are captured by the following memoirs and excerpts. These passages enable readers to observe how rural life in has changed over time..

Childhood Duties

Lew McGregor:

I was four years old. I had little things to do. By the time I was seven years old, I was splitting and piling wood, carrying wood into the house, lugging a pail of water in and taking ashes out from the stoves. I fed chickens and carried water to them. Most of the farm boys were going to the threshing when they were twelve. They might be in charge of a team.47

Margaret Redmond:

I was born in Watford, Ontario, on July 30, 1913. Every morning Mother handed me a pan with the order, “We need potatoes and peas or beans” or whatever was in season. And I went out to harvest them from the garden.

By mid-morning she would remind me that it was time for the mail, which in those days was left in our mailbox at the corner, nearly a mile from home. There was a butter factory at the corner and the butter maker's little girl and I always had a play together. Sometimes we went across the road to visit Mrs. Cook, who made good cookies, and we had a little swing in their big wooden swing.

During the day our cows pastured in a field on the other side of the road, a few rods north of our gate. Every morning, old Sport, our English Collie, and I drove the cows to pasture. And every evening, we had to go for the cows. Sport went back over the field by himself, visiting every groundhog hole on the way, rounding up the cows and bringing them back to the road, while I played golf with an upside down cane and road stones for golf balls. To entertain me in my spare moments, my old mother cat supplied me with an annual litter of kittens for playmates.

Each summer I raised a family of ducklings. One night, a board fell on two of them. My cousin and I spent the next morning digging two graves, nailing slats together to make two crosses, gathering dandelion bouquets and properly interring the little ducks with the Twenty-Third Psalm, the Lord's Prayer and the rhyme “Ashes to ashes, dust to dust, If the Lord won't take you, the Devil must.”48

Lottie (Graham) Davidson preparing to unload hay. Courtesy M Miner.

Beef Ring

Jean Janes:

There were at least 67 members in the group. The organization was essentially a co- operative among farmers to ensure they had fresh beef weekly. Full members contributed a beef each season which lasted from March to December – 40 weeks. The beef was to weigh 400 pounds dressed. George Janes used the slaughter house on the home place at Lot 13, Con. 3 NER [Brickyard Line].

Beef slaughtered one day and cut up the next was placed in white-handled, cotton bags according to the chart, so that a fair rotation of meat was maintained. In addition the meat was weighed. Those who contributed a whole beef received 10 to 11 pounds while those who went together with another received half the weight. The following day, the beef was delivered and the bag was hung on a hook on the mailbox.

The system worked well except for one forgetful farm woman who often neglected to put the second clean bag out on the mailbox. George put up with this inconvenience several times but finally, in frustration, took a hammer and spike on his next trip – she again had forgotten to put out the clean bag. George took the spike and hammered it through the piece of beef onto the mailbox! She did not forget her bag after that. Beef rings went back to 1910 and would have been delivered by horse and buggy.

Other butchers were: George Legatt, George Matthews, and Hansen Holbrook. The person contributing the beef drove the butcher around to deliver the beef. This particular ring closed in 1952- 53 as rented locker freezers became available in Watford directly across from the Bank of Montreal. In time, home freezers took over from lockers.49

Arnold Watson

We never belonged to a beef ring. We always killed our own beef and pork. The pork was dried down and then we fried the pork. That was better than any meat today. Beef would be cut up into chunks and put into sealers and then cooked in the sealers. We used to do boilers full of stewed beef too. Laverne Hawken built a locker in Arkona and we had meat in there until we got hydro and then got our own freezer in 1947.50

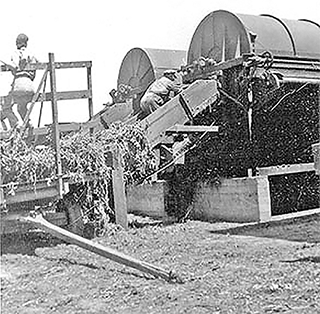

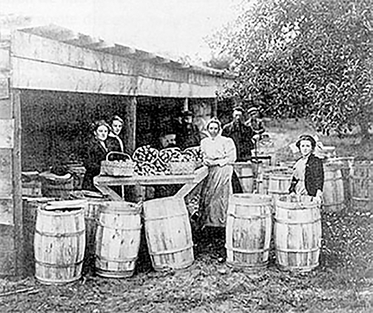

Pea Viners of Village

Dorothy Wordsworth:

Our community was growing peas for canning. There was a viner for shelling peas near Village. Yields were good but peas were a heavy crop to handle and required extra help. Delays caused by many loads reaching the viner at the same time wasted valuable time for the farmer. Pea harvesting and haying operations also conflicted.51

Janet Firman:

Dad grew peas for Canadian Canners and I remember going with him with loads of peas, pulled by horses, to the pea vinery just north of the village, early in the morning. What a smelly place!52

Ron Sewell:

Peas had to be a certain tenderness when harvested. They had this pea viner and it was a huge structure with a big rotating drum driven by a steam engine. This thing shelled peas. It was all encased in rubber and there were holes in it. As it rotated, it beat the peas and broke pods open and the peas would run down a chute to be carried away in bushel crates. Peas had to be in small containers, so the air could get to them or they would spoil. So they had to get the peas freshly done at the viner and get them to the Forest canning factory.53

John Smith:

Harvesting of peas began in 1931. Power was supplied by a portable steam engine owned by Les McKay of Village. More power was needed for additional viners so two large tractors were brought in, supplied by Jack Tanton and Mr. Kernohan. Pea vines and pods made excellent forage for cattle. Farmers hauled it away and the stack was always used up by spring. Any spoilage was hauled away for manure and orchard mulch. When a new harvesting machine (combine) became available, cutting and threshing of peas was done in the field eliminating the need for viners. The viners were closed in 1957. Village residents were happy to see this operation go. Seepage from stacked viner waste found its way into Spring and Bear Creek. The odour from the pea stack and seepage were truly obnoxious!54

Pea viners at break time: The two men standing on the right are Carroll Goodhand and Frank Cundick. Sitting in the centre is Hugh Freele. Courtesy P Evans.

Verne Kernohan:

I grew peas for three years and made money the first two. A good crop was $100 per acre. I went in the hole the third year because of aphids. Pea growers used a mower to put peas in windrows and a Cockshutt hayloader to load them onto a wagon. Cockshutt had the only hay loader with a steel base. Lloyd Cook had the hay loader. Peas were harvested in early morning so they wouldn’t wilt by the time they reached the canner. Canadian Canners provided three different varieties of seed, early, late and middle.55

Chickens and Ducks

Lew McGregor:

I used to hatch a bunch of duck eggs every spring and never had a female duck to set the eggs under so we used a chicken. With the hen, we’d watch when she left the nest and then we would sprinkle the eggs with water to soften them, just as a female duck would. Soon, the duck eggs would hatch. Funny thing was the chicken would lead the ducklings down to the water and stand there while the ducklings swam around. Then, she’d cluck away at them and the ducklings would follow her back to their holding pen. Most years I had anywhere from 50 to 75 ducks.56

Winter in the Country

Lew McGregor:

We never drove horses other than winter time. We always had a car. When my younger brother was born in 1937, my mother went to the hospital on Halloween and stayed there for ten days. (That’s not going to happen today.) They brought her home by car out Townsend Line to #9 Sideroad. They met the car there with horse and sleigh and hooked it onto the car and towed the car to the farm. Roads were basically impassable. Snow stayed that year until March.57

Repairing a corn binder. Courtesy I Janes.

Harvesting Corn

Lew McGregor:

I don’t remember the year but it was a terribly wet fall. The binder wheel would just slide when we ran the binder – even with extra horses pulling. Eventually, we wound up cutting the corn with sickles. By today’s standards it was a small field – only 8 or 10 acres but it had to be cut and stooked so we would have the feed for the coming winter. We would come home from school and cut and bind the corn stalks by hand. We could hardly carry them. In the wintertime, the stooks of corn would be frozen to the ground. We would use a horse and chain to tug on them and chop them loose with an axe. Then we would tow it to the barn. Sometimes we would pull off the cobs to grind or shell for feed. Stalks were either fed whole or chopped. That was quite the job getting that corn out of the field.58

Mary VanderPloeg:

One year dad rented 20 acres just across where Bert Lester lived. Dad planted corn and what a good crop it was. That winter was sunny and without much snow so he decided that Mr. Tanton who did a lot of custom work would not be needed. So my dad and I set out to pick the cobs off by hand. Neat piles of corn were made between the rows. Row after row, at the end of each row we would look back and see the beautiful sight. At the end of the day, we’d hitch the tractor to the wagon and proceed to throw them on the wagon. It took us all winter, but we didn’t care. In the end we had feed for the livestock.59

Harvest Excursions

Ron Ellerker:

The first year I went out I was 15 and the next time 16. They wanted people to go West to help get the harvest because all older men had gone off to war. The government wanted us to do this. It was five to ten dollars to go out and back by train. We worked like the devil for the rate of seven dollars per day, which was good money. When we were all out West, our parents were not too happy — particularly the second year I went.60

Advertisement for Labourers in Winnipeg: $10 TO WINNIPEG FROM ALL CANADIAN PACIFIC STATIONS IN ONTARIO ADDITIONAL FARM LABORERS’ EXCURSIONS TUESDAY, AUGUST 30 TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 6 Free transportation will be furnished at Winnipeg to points on Canadian Pacific where laborers are required East of Moosejaw, including branches and at one cent per mile each way West thereof in Saskatchewan and Alberta. Special trains from Toronto to Winnipeg on above dates Ask any Canadian Pacific Agent for Particulars SOURCE: Forest Standard, 1910.

Sharon Butala:

Harvest excursion trains played a minor part in populating the West since some men arriving (from the East) never returned home. They filed on a homestead, settled in and became farmers themselves. Some fell in love with a woman on the farm where they worked, and when the time came to go found they couldn’t leave her behind, so they stayed.

Harvest excursioners worked hard for their money. Some farmers had accommodations for the harvesters, but others provided only a hayloft or spare granary. Some threshing outfits that travelled from farm to farm provided a sleeping car for their men. There seems to have been few complaints about conditions, largely because the weather was good and the men worked such long hours at tremendously hard physical labour, they were so tired they could have slept anywhere. They had come out to harvest and harvest translated to stooking, pitch forking sheaves up onto wagons and then again into threshing machines. The last harvest excursion ran out West in 1929.61

Sales Barns

Lew McGregor:

It was a lot of fun over at the Hollingsworth Sales Barns at Watford. They had pens outside for selling horses and cattle. We sat up on the bleachers while animals were brought in from the holding pens and into the ring. They were sold and then returned and we would get a kick out of Gord. He just loved it. His grandchildren wrestled pigs and calves around the barns. Gord would enjoy that. He was a colourful character, Gord Hollingsworth. There are a lot of those boys out there yet, I got to know a few of them. Russ, the youngest, became an auctioneer too.

The sales barns were located in the northwest corner of Watford. Houses are built there now. Frances, Russ’s wife still lives in the brick house to the best of my knowledge. The barn was torn down. And another thing Gord handled was a machinery auction. Machinery from the garage trade-ins would all be brought to the field on the farm and Gord would auction them off. A food booth would be set up in the field corner — it was a big day.62

Fran Hollingsworth:

Around 1938 Gord Hollingsworth, an auctioneer, started his Livestock Sales Yard business on Front Street, Watford, behind Gribben’s Mill (which is currently known as McNeil’s).

Prior to 1950, he moved his business to Victoria Street, where his father-in-law John Bryce had already built a house. The business included 3 barns and an office. The first barn … had originally been the drive shed used at the Bethel Church on 15 Sideroad. This barn held calves, and hogs.

The barn that was used for pigs was already on the property, and was located closest to the house. The office was between the pig barn and the far [first] barn.

Gord Hollingsworth Stock Yards and Auction Barn, Watford, 1949. Courtesy B Hollingsworth.

There were pens built outside in the field between the two barns before the third barn was built in the 1960’s, and was appropriately called the middle barn. It was a pole barn, which came in sections and was assembled on site by a company from Kitchener. This is the barn where the cattle were sold. Gord sold livestock, conducted farm auctions and also auctioned houses and household furniture. His son Russell became an auctioneer in 1950. He sold the pigs until Gord retired and then took over selling the cattle while Gord’s grandson Jim Hollingsworth (John’s son), who was also an auctioneer, sold the pigs and calves.

Originally, the sale was started at 2:00 p.m. every Saturday in the fall and winter because this is when the farmers came into town. It was held on Friday night in the spring and summer. The Friday night sale started at 7:00 p.m. By the late 1950’s, the day had changed to Friday. In the winter, the sale was held on Friday afternoon and when the time changed in the spring, the sale was held on Friday night.

Russ would be selling cattle in the middle barn and Jim would be selling the pigs in the pig barn. When the pigs were all sold, Jim would move to the far barn and sell the hogs and calves.

Most of Gord Hollingsworth’s grandchildren, when they were old enough, worked at the sales yard doing various jobs, such as booking in the cattle and pigs, bringing the livestock into the ring to be sold, and helping the farmers load the animals that they bought into their trucks after the sale.

Gord Hollingsworth passed away April 3, 1963. The Sales Yard continued until December, 1981... Fran Hollingsworth, Russ’ wife, still lives in the house on the corner of John and Victoria Street.63

Rural Lifeline

Mac Parker:

After World War II (1946), Ivan & Evelyn opened a grocery and gas station called “Parker’s Fireside Store” at the same location as the egg grading station. They developed a grocery delivery service where the customer mailed in their grocery orders and it was delivered the next day. This flourished, especially when the new Canadians from Holland started arriving from Holland in the 1950s. They had large families and were allowed to charge until the milk or pig cheque came in. This business was closed in 1978 and not one new Canadian family owed money.64

Maple Syrup

Harold Zavitz:

When the pioneers came to this area the natives were making maple syrup by heating stones and putting them in hollowed out logs filled with maple sap. In this way they were able to steam out a lot of the water and finish up with a sweet, clear syrup that was great as a sweetener for their food.

Lambton County was known to have some of the largest hard maple forests of Ontario. Hard maple (or sugar maple) must have good drainage, so with the rich soil and rolling land was an ideal maple area. As the township was settled a great deal of the forests were removed as agriculture became more important. At first, most farmers kept at least 10% of their farms in wood lots. At present there is very little maple left in Twp. and just a few producers.

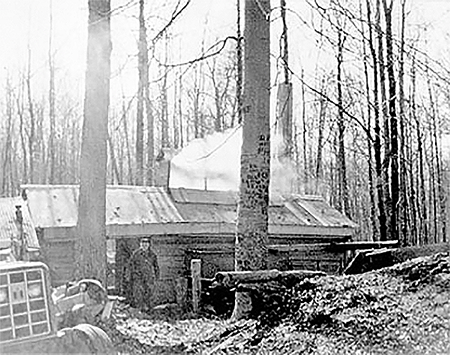

Sugar bush and Harold Zavitz’ sugar shanty at the corner of Nauvoo Rd. and Tamarack Line. courtesy H Zavitz.

Nearly all made maple syrup in the spring. They boiled it down in iron kettles which were used for everything else too. The kettles came from England. Often the syrup was boiled down to sugar and stored in cakes for sweetener during the year. Molds to form the cakes were from wood.

As time went on, around 1890, tin was brought to the area for pots, pans, etc. Then sheet metal shops came into being. Arkona, Watford, and Forest all had these shops. They made pails, pans and many items that helped the area families.

Around 1915 companies started manufacturing syrup evaporators. By 1920 many farms purchased these and syrup was made in large amounts. It became a saleable product which was taken to the Sarnia Farmers’ Market and to London. It was also sold to those in the area who did not make it.

I have made syrup for over 50 years at three different locations. For the last 35 years I have leased Keith McPherson’s bush at the corner of Nauvoo Rd. and Tamarack Line.

In 1971 Lyle Sitlington closed his egg grading station in Watford. Wesley Smale took the job of removing the old insul brick building. He took it down in sections with his backhoe. I hired him to take some of it to McPherson’s bush and put it back up with the Watford street number still on it. I put a roof on it and made a true sugar shack. We used this building until 1987. Some of the sap buckets we used were made in Watford, in Winston Brown’s sheet metal shop.

In 1963 I purchased an evaporator and all the equipment with it from Lloyd Cook of Village. It is no longer in use, but it served for 24 years, first in a bush I owned in Bosanquet Twp. and then in McPherson’s bush. Lloyd had used it for about 60 years previous to that.

Adam, Kris and Jason Boyd gathering sap in sugar bush. Courtesy S Boyd.