Good Times in Bad Times (The Great Depression)

Political meeting.

by Dr. Greg Stott

Catastrophes and difficult times tend to breed nostalgia of a particularly distorting kind. In the dark days of World War I and the decades that followed people had a tendency to look back at the period before August, 1914 as a period of “lost innocence,” a halcyon period swept away by the tumult of war. The less palatable and difficult aspects of the pre-war period tended to be downplayed, even forgotten, in lieu of what came after. The Great Depression has given rise to similar readings of the past and developed its own set of mythologies. In retrospect the 1920s have been painted as relatively prosperous times.

In the popular imagination the 1920s have been remembered as the “Roaring” or “Sunny, Funny Twenties.” For the majority of North Americans, however, the decade was not a period of unparalleled prosperity. A serious depression at the end of World War I had hurt farmers hard. The period of 1919 to 1921 was a difficult one, fraught with deep-seated tensions. It was a period of labour unrest and strife — most apparent during the tumultuous and bloody Winnipeg General Strike — that, while perhaps distant to the predominantly rural and agricultural Township, would certainly not have passed unnoticed. Things had improved during the 1920s. Prices rose and farmers were able to offset some of the debts incurred during the war. However, most farming families struggled through this supposedly “roaring” decade. Some years were better than others, and the individual circumstances of individual farming families played an important role.1

Ernest Albert Edwards' combine, 1938. Courtesy L Koolen.

In 1929 the economy of Canada was generally good, and many businesses seemed to be doing well. There were regional inequalities of course, and labour difficulties. Things in the Maritimes were certainly less satisfactory than further west. In general, however, Canadians were overproducing. There seemed to be a major boom in agriculture, fishing, pulp and paper production, mining and smelting, transportation and automobile production. But in a period of only a few months things seemed to change and the apparent prosperity began to wane, and wane quickly.

There was a complex interplay of external and internal causes. To a certain extent the economic difficulties were a result of lingering effects of the dislocations created by World War I. Great Britain was unable to emerge from the conflict to its former role as an economy that stabilized an inherently unstable and wildly fluctuating world economy.

The United States might have taken up that role, but did not, and when prices began to fall in 1929 the U.S. began to limit imports in order to protect domestic outputs from competition. This was the action taken by most countries worldwide. American banks began to cut long-term lending abroad just as long-term lending at home began to decline. Short-term credit was also being cut. All of these changes and actions worldwide intensified the shock felt in October 1929 when the stock market crashed and prices in overproduced goods like cereals contributed a massive wave of deflation.

Canada was one of the hardest-hit countries because its exports declined sharply. Prices for wheat, fish, timber and base metals fell more quickly and steeply than the price of imported manufactured goods. There was excessive overproduction and prices were falling. In general business and many citizens had accumulated a great deal of debt. Income was plummeting but interest rates on debt remained high well into the 1930s. This meant catastrophe. During the downswing that reached its lowest point in 1933 the gross domestic product of Canada fell by an astounding 29 percent. National income in 1933 was just slightly over half of what it had been in 1929.

There was a slow recovery after 1933, but it was uneven. Wheat farmers, for instance, did not recover. Wheat that was selling for over a dollar per bushel in 1929 fell to about fifty cents per bushel in 1932. Farm incomes by 1936 were still only about a third of what they had been in 1929. The year 1937 marked a new slump that would not be overcome until the outbreak of war in 1939.2

While many in would certainly have heard of the stock market crash in New York, and many may have anticipated that, as a result, they could expect to feel some of the economic fallout, it did not necessarily hit them right away. Many went about their regular routines, and some continued to build up their farming operations, building new chicken coops, acquiring new equipment, probably expecting that the crisis would not deepen too much. In October, 1929, as the crisis in the financial sector deepened, readers of the Watford Guide-Advocate were treated to an optimistic report from the eighteenth annual Investment Bankers Association of America conference, a meeting of North American bankers held in Quebec that year. In a buoyantly confident statement the article noted that the many delegates representing institutions from all over Canada and the United States “symbolize the driving power behind industrial progress on this continent.”3

Androck Employees, 1930s: Roy Hollingsworth, William Hollingsworth, Kenny Williamson, Kath Elliott, Gerry Piercey, Jessie Hayward, Peter Garson. Courtesy D Hollingsworth.

For the most part, life in late 1929 and early 1930 continued on as usual as the people of , Watford, Forest and Arkona anticipated winter's arrival. In Watford the Roman Catholic community extended their sympathies to their incumbent priest Rev. Father Edward Glavin upon the death of his father, while in Arkona, the Women's Institute met as usual in November, and the United Church there held their annual fowl supper. The young people of Township's Zion United Church were engaged in preparations for presenting their play “Eyes of Love” at the distant venue of Uttoxeter. In Watford it was noted that:

Badminton is in full swing these evenings on the court at the Armory. There is still room for more members. Come along and enjoy this fascinating game. The fee is only $2.00 for the season, payable to the treasurer Miss Eleanor McIntosh.

The only possible hint of concern about the economy might have been struck by a meeting of Watford's business community. It was announced that:

Watford businessmen will meet in the Armory this (Friday) evening at 8 o'clock to discuss plans for the promotion of Christmas buying in Watford and to arrange for a Community Christmas Tree on Federal Square as in former years.4

By the spring of 1930 things were becoming a bit more dubious. A piece in the Watford Guide-Advocate warned that “[d]uring the six month period ending March 31st, 1930 business has had to deal with some problems which are perhaps more basic and difficult of solution than those with which it had to contend in 1921.” The piece continued by explaining that “[o]wing to the depression of the stock market, about October 1st last, nearly every line of business was retarded and while stock markets do not greatly affect the basic conditions of a country, they do affect individuals and their purchasing power.”5

As Russell Dunham explained, as far as money was concerned, it depended upon the year. He elaborated when he said, “But [during] Depression days we existed; we had food. We had no money to spend.” He recalled further that times were not easy for many as:

a lot of people… didn't have any work…. [The] prices we sold things for were very, very low but as least we got a little bit for them. But we sold our beef for three cents a pound, and I forget how cheap eggs went, but they were pretty low anyway. But then when beef went up to nine cents a pound we thought that was really coming. And that would be pretty small by today's prices. We weren't able to go out and buy things, although during the Depression I remember getting a new sweater for Christmas and also a blue shirt. And one chap came and stayed over night, like just going through the country, begging, asking for food and lodging for the night or something, and Mother kept him over night one night, and he come back the next night and stayed another night. And a couple of days after that I was looking for my blue shirt and they said, “Oh, it's hanging up there.” [I] Never did find the blue shirt again, we figure this Harry O'Neill, the guy that stayed over night, must have put it on and wore it home. Or wore it home, he didn't go home, I don't know where he went. I don't know, but I never saw the shirt again. But people used to go around looking for food, and if they were in the village they would put them up in the jail cell overnight, to sleep there, and away they'd go the next day….6

One Watford area farmer explained that, “[T]here used to be different tramps around you know and come in and ask for a bite to eat, you know. Used to see them in the Depression years, 8 or 10 of them riding the cars on the railroad; see the railroad went through my farm.”7

Sometimes the tramps or hobos would come onto the farm during the maple syrup season to help out in the bush in return for food. There were also berries to help the unemployed and cash-strapped farmers too. One couple recalled that:

[O]n a farm… seemed to be about the best place to be, you know, because you had your own milk and eggs and syrup and we had lots of wild berries that grew in the woods…. Raspberries and blackberries and dingleberries; blackcaps; and they were right in our woods and… you would help yourself to if you wanted to and we had fruit just by working for it… and that we had a lot of stuff for eating; I don't think we was ever hard up for something to eat.8

Carman Hall cutting corn in early 1920s. Courtesy L Hall.

Township Council had to face the new economic realities. Certainly the basic business of local government continued unabated as funds were allotted to those who hauled gravel, maintained roads, monitored noxious weeds, and negotiated, planned, and worked on necessary drains. While the full impact of the depression was not immediately felt, when the economy reached its lowest ebb in 1933 Council was forced to contend with the fact that many of the township's citizens were in dire straits. Many beleaguered farmers forfeited on their taxes or begged for a form of tax relief. Others were finding it difficult to even afford the basic necessities of life. In March 1933, Council authorized that L. S. Cook be paid $1.85 for supplying flour to one unfortunate resident, while James Jones was to be given $1.05 for supplying the same individual with meat. At the April 3, 1933, meeting of Council, the Council passed a motion that $3.67 be paid to Gordon Vance for groceries and flour which he had procured for a destitute township resident.

Given the circumstances, the court of revision was faced with a multitude of complaints about high taxes which, in some circumstances, were lowered. Council was also grateful to Orville Williamson for shooting a dog that worried local sheep, and voted him the sum of $5.00 for his efforts. A further $10.00 was paid to Thomas Westgate Jr. after his sheep had been worried by dogs, and an additional $5.00 for shooting the culprit, while his father, Thomas Westgate Sr., received $25.00 for three sheep killed and fourteen worried. The Westgates, however, had been comparatively lucky, for William Woods received $59.00 as compensation for nine sheep and lambs killed and others worried.9

Given the nature of the Canadian economy, with so many men and women engaged in primary production in mines, forests or on the farms, the winter months were often the most difficult for those dependent upon seasonal employment. The Great Depression made the traditionally lean months even more difficult. As a result Watford Council also had to deal with the difficult times. The numbers of unemployed and indigents within the village is difficult to determine. It is likely that indigents followed the railway lines looking for work and, when necessary, handouts. As a small municipality Watford would have to contend with its own working poor and unemployed as well as a possible inundation of outsiders desperate for work or help. Through the English Poor Laws of the sixteenth century, Canada had inherited a tradition whereby poor relief or “the dole” was left to the local municipalities. Under normal economic circumstances, municipalities were generally able to cope; however, with the heightened crisis, many places, large and small, urban and rural, were caught in a desperate situation. Municipal coffers were often stretched to the limit. At the March 11, 1933, meeting of Watford Council an indication of this crisis was illustrated when Councillors Dick and Hollingsworth moved and seconded a motion “[t]hat no relief be given after April 1st 1933.” The motion was carried, possibly anticipating the start of spring planting and the likely ability of those out of work to find temporary agricultural employment, which meant that the municipality could see its way to refusing to extend relief during the warm months.10

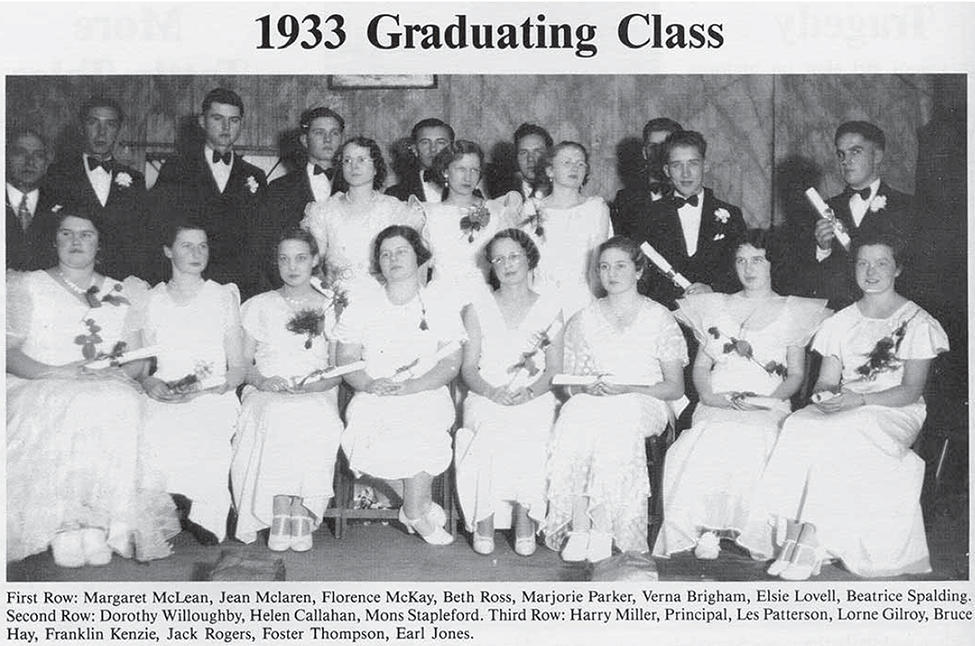

Graduates of Watford High School, 1933. Courtesy ELSS Centennial Book 1891-1991.

The Council's refusal to extend relief in the spring did not mean that Watford's Council ignored the plight of those who were caught in difficult situations. At the regular May meeting Council paid $1.25 to W. C. Towries for “meals of transients” and a further $3.50 to C. C. Miller “for services re transients.” They too had to continue the basic work of running a municipality, whatever the economic circumstances. Money was transferred to the Library Board; John Dobbin was still paid for scraping village streets; Gordon Jamieson was remunerated for “cleaning intakes and streets.” The sums of $600 and $800 were transferred to the Public and High Schools respectively, and James Blezard, the village constable, still received his $32 salary and an extra $10 for ringing the town bell. Perhaps it was a sign of the times, too, when Council paid W. H. Harper for the funeral expenses of a youngster; possibly the child's bereaved parents had been unable to afford the costs involved.11

Most Canadians subscribed to the idea that economic shortcomings were the fault of the individual. It was generally held that a man (and it was generally still assumed that a man was the chief and rightful economic provider) who was facing a financial crisis was at fault for having either not worked hard enough or for having made bad decisions. There had been depressions before, of course, such as the one that had followed World War I, and the nineteenth century had been punctuated with regular economic downturns. These depressions and recessions, however, had generally lasted a year or two at most. The sheer numbers of people caught in the maelstrom of the 1930s caught everyone off guard and led many to slowly come the realization that economic misfortune was often beyond the control of any one individual or group. However, many people, especially male breadwinners, felt personally responsible and this led to despondency and in extreme cases suicide by men who felt they had failed in their basic responsibilities to their families. There were strains upon marriages and in families as a whole as they attempted to cope.12 As a general rule of thumb those in rural areas in Ontario are believed to have been better able to weather the storm, given that they had food to eat. It was certainly not a happy interlude.

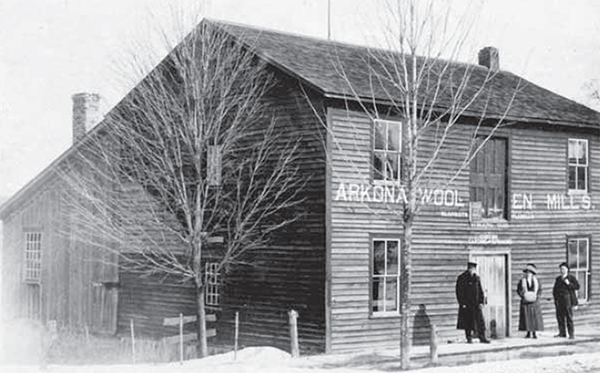

Arkona Woollen Mills: Alex Dickson built the Woollen Mills in 1860. They burned in 1939. Courtesy W Dunlop.

Thinking back about life in the 1930s one Watford resident explained:

Well, I know that we were very hard up. My grandmother and mother had to sew for us, and we had one good dress and that was it. My sister and I were the same size and the one pattern had to do for us both and they would buy the same material to save money. 'Cause there were five of us I'm telling you it wasn't easy. My father's business at that point wasn't too good…. [H]e also used to go around to people's homes. Instead of garbage collection, twice a year people would call up and say come and get my garbage. It would collect during the winter and about twice a year he would have to go around to the people's homes. They would call him and he would go and get it. So money was pretty scarce.13

Early in January 1932, one young farmer outlined many of the problems facing the family as the economic crisis deepened. As he recorded:

It has not got very wintery yet. We have our buggy all fixed again (except the top), we put the old crossbar in out of the milk wagon. Eggs are terribly cheap for this time of year, 18¢, Cream 20¢ we can hardly get enough money to keep things going. I hope times improve soon. All the wood we have had this winter is old rail fence and such like [it] with an occasional stick of hardwood. Last years coal is not all paid for yet.14

The situation did not entirely improve and in November 1933, the same diary reported that:

We have had a warm summer but very little rain in fact it isn't very wet yet, very little water in the wells…. The grain crops were not very good this summer but corn was quite good. Hay was good for first cutting, fair second cutting but too dry for any more, pasture were poor toward fall on account of the dry weather. We had a wonderful crop of melons this year, in fact we still have a few, potatoes were fair, turnips, nothing….15

Another farmer explained:

Times were tough, times were tough; we took 5 cents a dozen for eggs, sometimes 7 cents for them; about 12 cents a pound butter fat; I sold a 1000 pound critter one time and brought him into the butcher shop for 3 cents a pound live, $30 for a 1000 pound critter… and today [1978] I paid $1.09 for a pound for some beef today.16

The situation in rural Ontario did not go unnoticed by provincial authorities who were desperate to attempt to find a way out of the mess. Political leaders at all levels were often as much in the dark about how to dig themselves out of the crisis as most of their constituents. It must be remembered that few political leaders in power in the early 1930s survived politically to the end of the decade. The 1930 Federal election, just as the crisis began to be felt, had led to the election of Conservative Prime Minister R. B. Bennett, who was thrown from office in the 1935 general election. At the provincial and municipal levels the situation was equally tenuous. The government of Conservative Premier Ferguson lost power to the great orator and Elgin County Liberal Leader Mitchell Hepburn in the depths of the depression.

On April 21, 1934, Township Council met in a special session “to consider the advisability of taking action in assisting the farmers to procure seed grain pursuant to the provisions of the Seed Grain Act of 1934.” By the end of the evening Council passed the by-law that they do their utmost to assist their farmers. In the end Reeve Reycraft and Councillor Smith instructed the township's clerk, N. Herbert, “to have a few copies of application forms & above by-law typed for use of the Reeve and Treasurer.”17

Farmers were not the only ones who felt the pinch, of course. In June 1933 the teaching staffs at Watford's elementary and secondary schools signed new contracts with the village's school board. As the Watford Guide-Advocate reported, the incumbent teachers

renewed their contracts for another year at the reduced salaries designated by the board of education. The High School staff will revert to a five teacher school unless an unusual increase in attendance in the fall makes a sixth teacher again necessary. In the Public school, the four lady assistants will receive the salary of three, as an alternative to the board's decision to dispense with one teacher.18

SS#8 , 1936: Walter Eastman, Edna Lusk, Mabel Cadman. Courtesy WI Tweedsmuir Books.

The Great Depression wreaked havoc with the plans of those youths who had gone on to get further education with the hope of improving their economic prospects. Promising careers were put on hold and many left the big cities to return their parental homes in . In her late teens when the economic crisis began Gladys (Janes) Moloy, having finished her high school education, went to London to take courses at Beal Technical for a year of business training. The new economic realities, however, did not make the pursuit of a career easy. She explained that:

jobs were non-existent. I think there was one person selected from the school that got a job. My sister got a job in London and I came home and worked for one month for the lawyer there, Mr. Fitzgerald. And then in the Insurance office for about six months while Mr. Minielly's daughter was sick. And then I went to the Wire Works, supposedly for a month, and then I was there three years. And then I had the chance to go in the bank and I worked seven years in the bank 'til I was married.19

While many on farms were in relatively good shape compared with their unemployed urban counterparts, ownership of a farm was no guarantee of relatively smooth sailing. As Wib Dunlop explained:

At that time they didn't have a nickel to rub against another one and I started farming when I was twenty years old. My dad lost his farm where we were living on for thirteen years. I was born and raised on a farm. But I didn't know anything else. As soon as I got out of public school I was right on there threshing and that, same as everyone else. There was nothing else to do. No money, so in 1938 I rented a farm up in Plympton Township. I was up there for four years. My mother kept house for me. My dad was there by that time and brothers by that time in Arkona and all over. At that time you was so busy. You didn't have time to think about much of anything else.20

It is difficult to know how much children knew about the economic crisis. Parents may have attempted to keep the worst of their fears from their children. Those who lived on farms that were not heavily mortgaged probably weathered the storm better than those whose parents relied on waged labour. Children could not help but be aware of the world around them, and many recalled the prices for decades to come. As Janet Firman recalled “in the 1930s gasoline was 25 cents a gallon or 5 gallons for $1; an ice cream cone was 5 cents; a large red sucker 1 cent; licorice in the shape of a pipe or plug or a cigarette was 2 for 1 cent; the Forest Free Press was 5 cents an issue or $2 per year.”21

Whatever the ages or experiences of residents, while there was some relief from the extremes of the early 1930s towards the end of the decade, the catastrophe of the Great Depression would only be relieved by the catastrophe of war.

SS#10, 1935. Back row: Gordon Aitken, Jack McGillicuddy, Arnold Watson, Orville Williams, Rae Watson, Lloyd Bryson, Marjorie Tanner (teacher). Middle row: Bill Adams, Kenneth Bryson, Bud Cundick, Sherman Williams, Calvin Bryson, Pearl Brockton, Gladys Watson, Marjorie Williams, Florence Brockton. Front row: Bob Ross, Bud McMillan, Evangeline Bryson, Donna Williams, Hazel Brockton, Jean Bryson, Florence Williams. Courtesy A Watson.

Endnotes

1. James Struthers, “Great Depression,” Canadian Encyclopedia, McClelland and Stewart, 1999, pp. 1012–1013.

Lara Campbell, “‘We Who Have Wallowed in the Mud of Flanders': First World War Veterans, Unemployment and the Development of Social Welfare in Canada, 1929-39,” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, Volume 11, 2000, pp. 125–149.

2. Michiel Horn, “Great Depression,” Oxford Companion to Canadian History, Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 269.

3. Watford Guide-Advocate, October 25, 1929.

4. Watford Guide-Advocate, November 15, 1929, and November 22, 1929.

5. Watford Guide-Advocate, April 18, 1930.

6. Russell Dunham, October 12, 1997.

7. William Loftus McLean, interview by Brenda McLean, July 7, 1978.

8. William Loftus McLean and Annie McLean, interview by Brenda McLean, July 7, 1978.

9. Township Council Minutes, March 6, 1933, and April 3, 1933.

10. Watford Village Council Minutes, March 11, 1933.

11. Watford Village Council Minutes, May 1, 1933.

12. Denyse Baillargeon, “‘If You Had No Money, You Had No Trouble, Did You?': Montreal Working-Class Housewives During the Great Depression,” Women's History Review, Vol. 1, Issue 2, 1992, pp. 217–237.

Mary McKinnon, “Relief Not Insurance: Canadian Unemployment Relief in the 1930s,” Explorations in Economic History, Vol. 27, Issue 1, 1990, pp. 46–83.

13. Gladys (Janes) Moloy, interview by Brenda McLean, July 13, 1978. Transcribed by Karen Houle, December 2007.

14. Russell Dunham, diary entry, January 20, 1932.

15. Russell Dunham, diary entry, November 15, 1933.

16. William Loftus McLean, interview by Brenda McLean, July 7, 1978.

17. Township Council Minutes, April 21, 1934.

18. Watford Guide-Advocate, June 16, 1933.

19. Gladys (Janes) Moloy. Moloy explained that while attending Beal Technical she “boarded in London. If we could afford money to come home on the train or the bus we came every weekend. We got board very reasonable. My sister and I stayed together.”

20. Wib Dunlop, interview, 2006. Transcribed by Julia Geerts.

21. Janet Firman, “War & Depression,” notes in Township Archives.

Subscribe to this page

Subscribe to this page