My Home, My Palace (19th Century Domestic Architecture)

Fuller home on right, built 1887; Fuller home on left, built 1858: Th e house on the left appears to be Scottish Landlord style. Th e newer house does not appear to fi t any of Dr. Whebell’s models. Courtesy F Fuller.

by Glenn Stott

Some of the photographs in this chapter were taken by Carter & Isaac. W. W. Carter was the photographer; his wife Bertha Isaac Carter finished the photos and prepared them for delivery. Carter travelled by train throughout southwestern Ontario, going from farm to farm on a rented horse and wagon, taking remarkable photographs of families and their homes in the early part of the 20th century. He would ship his glass negatives home to his wife. The Carters were based in St. Marys from 1903 to 1908, then moved to Preston (now known as Cambridge) and later to Elora. The St. Marys Museum has a large collection of Carter & Isaac photos.

The Township of was settled mainly by hardworking European people who came in the 1800s to start a new life. Few had financial resources available to build large, commodious or architecturally-striking houses until much later in their lives. was a farming community where nineteenth-century homes reflected the simple, functional styles of a rural dwelling. Fortunately many still survive in 2008.

The original homes built by the pioneers no longer exist. Even the log cabins which remain most likely represent the second or third house on a property. For the most part, log cabins were made of squared logs, nine to twelve logs high, with dovetailed corners, measuring about 16 feet by 24 feet. Built in the 1850s, the Barnes/Vaughan cabin at 7009 Quaker Rd. is an excellent example of the usual 1½ story cabin most of the farms would have had.

In 1832 Roswell Mount, the Crown Land Agent who was charged with accommodating the first settlers coming to the area, built some shanties as temporary shelters. Constructed of green logs and slab wood rooves, they would have been abandoned for a more substantial structure as quickly as possible. Once replaced by a cabin the shanties would have been used later as a farm building such as a stable, a corn crib or a piggery, until they collapsed.

Brandon homestead, Lot 8, Con. 5 NER, built in 1872: Not all early houses were made of logs. Once saw mills were established, many homes like this one were built with sawn lumber. Renovated on the outside, this building is now located at Lot 11, Con. 5 NER and used as a woodshed. Courtesy D Brandon.

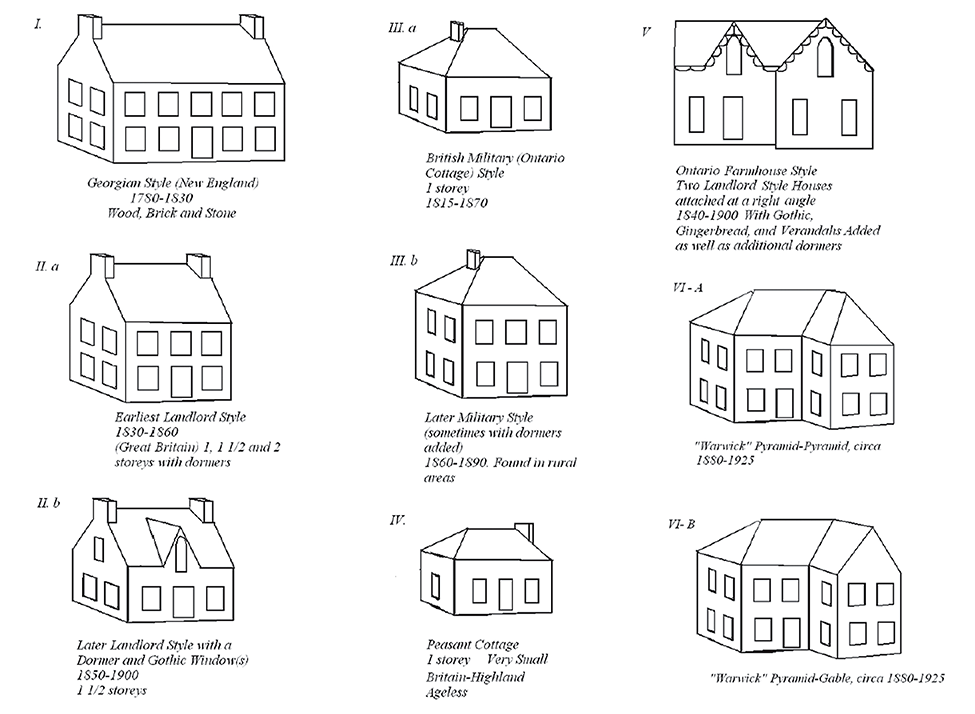

A Classification System of rural nineteenth-century architecture proposed by Dr. Charles Whebell of the University of Western Ontario in the 1980s1 breaks the fundamental architecture of rural Ontario into five basic styles classified by the date of construction, the origin of the design and the background of the builder/owner. Additional architectural features, such as porches, type of siding, window design, columns and gingerbread (a type of external wood trim used along the roof and dormers for decorative purposes) can be described as “window dressing.” A modern

example might be the purchase of an automobile: one can purchase a sedan, van, suburban utility vehicle (SUV), or truck. The model is basic, but the options that can be added to it are endless. With rural nineteenth- century homes in Ontario the same rule applied: they were basic structures but they came with many options.

A number of excellent books have been written about the early architectural styles of Ontario houses, including The Ancestral Roof; London: Site to City; At Home in Upper Canada; The Governor’s Road; and Victorian Architecture: In London and Southwestern Ontario.2

The Marshall home on Arkona Rd.: The Marshall house design does not fit any of the models and may represent an American design. Courtesy P Janes.

The following outline is not an authorized architectural formula but a very simple grassroots approach to examining the house designs found in in a quick and easy fashion. Dating a house is very complex, if not impossible, without examining land assessment records, deeds, pictures and family lore.

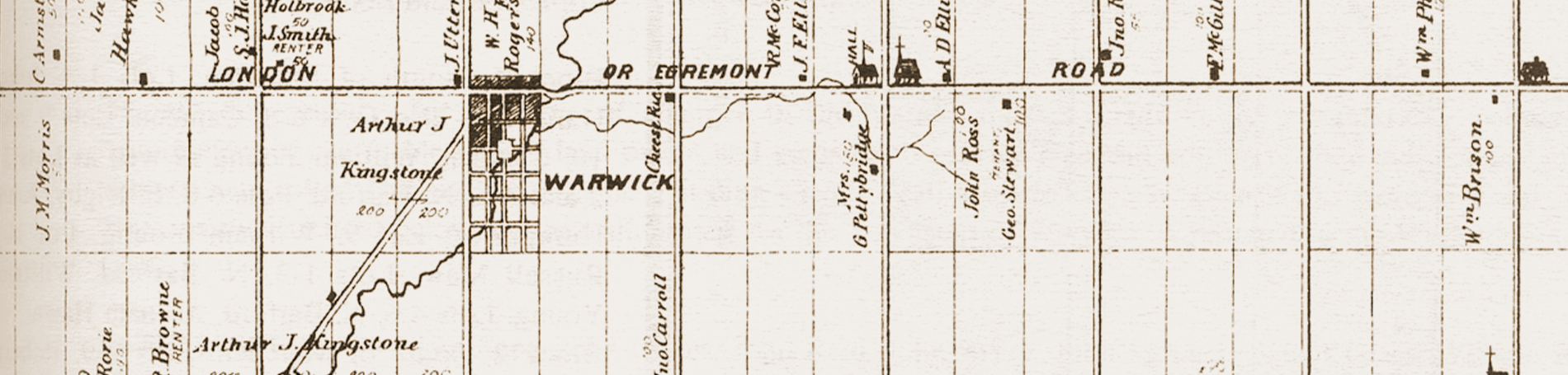

The earliest dwellings in that still stand originate in the 1850s and increase in numbers as the 1870s arise. The oldest known houses in are probably the Utter House (c. 1843) in Arkona at 8529 Townsend Line, the Marshall House (c. 1845) at 6964 Arkona Rd. and the McEwen house at 7042 Egremont Rd.

The five basic designs, with approximate dates of use, are:

I. Georgian Style: 1780–1830

II. Scottish Landlord Style

a. Early Scottish Landlord Style: 1830–1860

b. Later Scottish Landlord Style: 1850–1900

III. British Military Style

a. British Military Bungalow Style, also known as Ontario Cottage Style: 1815–1870

b. Later British Military Style: 1860–1890

IV. Peasant Cottage Style: 1780–1900

V. Ontario Farmhouse Style: 1840–1900

VI. Style

a. Pyramid-Pyramid Style, 1880–1925

b. Pyramid-Gable Style, 1880–1925

Georgian Style

Georgian Style homes were rare in Township because they were usually built by wealthier, well-settled families with United Empire Loyalist roots; they are mostly found in Eastern Ontario or the Niagara Region. Georgian Style homes are also found in the United States, especially the Eastern United States.

One of the only buildings which resembled a Georgian Style home was the Maple Leaf Hotel in Village. It had five bays, i.e., a combination of five windows/doors across the front. The two-storey Georgian, by far the most common, would have had a total of ten windows/doors across the front. These buildings were very symmetrical with two bays on the side walls. There appear to be no original Georgian homes left in , although the style has often been copied in modern house design.

Maple Grove (Leaf ) Hotel, Warwick: Built in 1835, this was one of the oldest hotels in the province. It was destroyed by fire in 1947. The first library in Warwick was located under the stairs in the lobby. The style is classic Georgian with five bays in the front. Courtesy R McEwen.

Scottish Landlord Style

The Scottish Landlord Style was very common in . It was based on the style of house built in rural Scotland and England by the landlords for whom many of the settlers once worked. To them, according to Whebell, having a home similar to that of their former employers represented their vision of ultimate success. As a result, this style, and its many variations, was the most common of nineteenth-century designs in rural Ontario. In their book The Ancestral Roof: Domestic Architecture of Upper Canada, McRae and Adamson identify this style as “Ontario Classic” as it was so common.3

The Scottish Landlord Style was initially a symmetrical structure which consisted of three bays on the front and two windows on each of the side walls. It originally was a one-storey structure. Since two-storey buildings were taxed more heavily, a dormer may have been added to make a house a 1½ storey, which still avoided the higher tax. A summer kitchen was often attached to the rear portion. In some cases, however, the kitchen was the original structure and a Scottish Landlord section represented the family’s new addition. (Summer kitchens were very commonly added to every style of house and varied in size and complexity.) A Scottish Landlord Style house located at 7484 Egremont Road had two French doors (since replaced with modern windows) on either side of the front door, a truly unique feature for Western Ontario. The two-storey Scottish Landlord Style building was the preferred style for many of the early Ontario hotels.

British Military Style

Former soldiers who had been to the exotic parts of the British Empire brought back certain unique styles which were reflected in the houses built either by them or their family members in the 1850–1900 period. A unique feature of the British Military Style structure is its hipped, or pyramid-shaped, roof, which was typical of India. This roof was used on most British military buildings of the period, including blockhouses located in forts. The house still had the basic three bays, with two bays on each of the side walls. A one-storey British Military Style structure, found in towns and villages such as Watford, Forest, Strathroy, Adelaide Village and London, became known as the Ontario Cottage Style.

Farmers in , however, needed more room. As a result they built this structure into a two-storey dwelling. As time went on and prosperity arrived, one or two similarly-shaped additions were built. Many combinations of this appeared, coupled with machine-made gingerbread and windows. has several examples of such houses, which represent the largest of the nineteenth- century farmhouses. Porches, bay windows, widow’s walks (a railed rooftop platform), and buttresses have been used to enhance these late Victorian homes and make them striking.

Peasant Cottage Style

Perhaps the most common house for many farmers was the common cottage, or Peasant Cottage. This was the simplest, plainest building, and was easily constructed without much assistance. It would have been the first structure built by a farmer once he was able to replace his log cabin. These homes were smaller in size, but still consisted of three bays across the front and perhaps only one bay on each of the side walls. They were usually made of wood siding with a normal two-sided roof or, occasionally, a pyramid roof. The Peasant Cottage was a universal design and was constructed during a period from 1830 to 1900. It eventually may have been used as a portion of a new house or as the back kitchen. Often such buildings were used by retired couples, a young married couple or single persons. A number of these Cottage styles, with the simple roof design, are still in existence in Warwick.

Willer homestead, a simple Common Cottage design with 1870s window frames. This house formed the centre of the Rombouts’ house standing at 6836 Zion Line in 2008. Courtesy L Willer.

Ontario Farmhouse Style

Ontario Farmhouse on Parker farm: Th is unusual wood-sided Ontario Farmhouse with gothic windows, gingerbread and

1870s-style window frames burned in the 1970s. A photo of this appeared in K. Ondaatje and L. MacKenzie’s book Old

Ontario Houses in 1977. Courtesy M Parker.

Often the Landlord Style was extended with the complete addition of another house, a copy of the original, forming an “L” or “T” shape. This gave it double the room and a unique Ontario farmhouse appearance. This represents one of the most common house styles found in Southern Ontario, which Whebell calls the Ontario Farmhouse Style.

In there are numerous examples, some even including three additions and forming an “I” shape. This style appears to be specific to Ontario and is not found elsewhere in Canada or in the United States. With the addition of verandahs, extra dormers, bay windows, gothic windows and/or exterior gingerbread, these buildings showed that the farmer and his family were very successful. These homes reflected the prosperity of the time, as a result of high grain and livestock prices during the Crimean and American Civil War periods. farmers took advantage of that prosperity, and the architecture showed a concern for style and appearance. The homes were very functional as well. However, many were kept simple in their design, without the added items. These houses were made of wood, brick or, in and Adelaide Twp., poured concrete. This style of building was constructed from 1860–1890 and reflected the British origin of ’s many farmers.

Ontario Farmhouse variation: A classic Ontario Farmhouse style with gothic windows, gingerbread and an unusual “I”-shaped design stands on the Geerts farm. Courtesy J Geerts.

With the five basic designs, most of the nineteenth century homes in can be identified from the basic form of the building. However, there are some exceptions which reflect an interesting element that arrived in the late 1800s. The Americans who immigrated to brought with them their own unique designs for homes. The Marshall House at 6964 Arkona Road, restored in the 1970s by the Roder family, represents one of these designs. First, it has only two bays on any of its sides. It also lacks the symmetry one associates with the usual Ontario nineteenth century design. In the Archives, there are examples of similar two-bay structures which resemble the Marshall house, such as the Wilson House at 8473 Townsend Line. In Dresden, the home of Josiah Henson is of a similar design and may reflect a similar American influence.

Warwick Style

After the 1880s, with the extensive manufacturing of wooden products, especially windows, trim and posts, a wider variety of

structures was readily available to the farmer or land owner. As a result, a wider variety of house designs made their appearance, including one style which features a commodious structure with the combination of two or more Military Style parts, with verandahs, bay windows and even towers. Many of the fine homes of display this design with unique modifications. These houses usually feature a front with only two bays, but the windows are much wider and often have stained glass components, bay windows or towers. Generally these homes can be dated as post-1890 and represent the ultimate success of the farmer and his family. Our Committee has chosen to call this the “” style (sketches VI a and VI b).

Dr. Whebell’s analysis of the nineteenth-century domestic architectural designs does not cover a later (1880–1920) two-storey style quite common to and other southwestern Ontario townships. This style combines the British Military and Ontario Farmhouse styles. It usually has a combined two-segment format in an L or T shape which always has one of its segments with a pyramid roof, while the other may be also a pyramid or could be a gable roof. These houses have a frontage of three to four bays, often featuring larger “picture” windows or stained glass windows and doors. Usually these large dwellings are made of white brick and demonstrate the level of affluence the farmer or landowner had reached by the turn of the century.

house builders utilized many of the natural resources of the township in the design, construction and decoration of their houses. Stone was not plentiful and as far as can be determined not used extensively in , other than in foundation construction. The eastern part of had a few poured concrete houses unique to the -Adelaide region. It is speculated that the owner of a gravel pit in Adelaide Twp., a Mr. Chambers, made gravel available at a reasonable price to his children and their spouses. As a result several of these poured concrete homes were built for his family because they were economical. A few of these houses still stand, although most have been abandoned and await demolition.4

Township was one of the leaders in the development

of drainage tile legislation and manufacturing, beginning in the 1870s. One of the offshoots of the tile manufacturing industry was the manufacturing of brick. There were several brickyards in the township, with McCormick’s, Auld’s and Janes’ being the most well-known. Brick became a standard siding for many homes, beginning in the 1860s.5 Brick siding would have been much more expensive than wooden siding or a log structure but would have had obvious benefits. Schoolhouses were built from logs at first but, as they were gradually replaced, they were usually sided with brick. By the 1870s, a white brick siding was the most common siding selected for a house, especially if the farm had prospered during the American Civil War period. Brick was also encouraged, especially in rural communities, because it reduced the risk of fire being spread from building to building.

In in the 1800s and indeed early 1900s, most farmhouses were still heated with wood. This required an extensive supply of firewood, which would be stored in a woodshed that was usually attached to the house.

The by-word for almost all homes built in the nineteenth century was “functional.” Even after one hundred years of remodelling, renovation and progress this is visible in those houses which still stand.

However, once the twentieth century arrived, house design took off with variations on many levels, which are far too complex to consider. house builders in the early twentieth century still utilized the abundance of gravel deposits to make cement block houses and cement veneer houses. Colonel Dunham’s original frame house on Lot 24, Con. 5 NER, built in an American style by Alonzo Sweet from New York State, was reconstructed in 1913 with cement block veneer after extensive storm damage.6

Wilkinson house, 6697 Egremont Rd. (Carter and Isaac photo): Still used in 2008, this late 1800s house reflects the style with Italianate Provincial buttresses and machine-made gingerbread around the verandah. Courtesy M Demers.

Ontario Farmhouse (Carter and Isaac photo, 1911): This house on Lot 25, Con. 3 SER is made of poured cement with a stucco coat in the shape of blocks on the exterior to make it appear more elegant. In 2008 this house is awaiting demolition. In front are Susie (Westgate) Davidson, Margaret (Chambers) Reycraft, Lizzie (Moffatt) Reycraft, Swanton C. Reycraft, Gordon J. Reycraft (in high chair) and the hired man. Courtesy B Reycraft.

Many years ago, the Federated Women’s Institutes of Ontario promoted a “House Log” program whereby home owners were encouraged to collect information, documents and photos which showed how their house looked over the years, as a permanent record to be preserved in a special place for future generations and future owners of the house.7 The idea of keeping a log of the house changes seemed to be a very valuable way of preserving one of the most important historical events a family would experience: the creation of the family home.

Despite their efforts, in and throughout the entire province, there is a very poor record of the history of houses. The houses which are recorded are usually the homes of the “rich and famous” such as Eldon House in London, Casa Loma in Toronto, or Lawrence House in Sarnia. Unfortunately, these do not represent the majority of houses in Ontario, especially in Warwick.

Endnotes

These links were used at the time of publishing in 2008. Some links may have changed or may no longer be active.

1. Dr. Charles Whebell, Professor of Geography, UWO, “Basic Architecture Styles of Ontario, 1780–1900″, presentation to Middlesex County Teachers in Fall 1983.

2. Marion McCrae and Anthony Adamson, The Ancestral Roof: Domestic Architecture of Upper Canada, Clarke, Irwin & Co., 1963. Nancy Z Tausky, Historical Sketches of London: From site to City, ill. Louis Taylor, Broadview, 1993. Jeanne Minhinnick, At Home in Upper Canada, Clarke, Irwin & Co., 1970. Mary Byers and Margaret McBurney, The Governor’s Road: Early buildings and families from Mississauga to London, University of Toronto, 1983. Nancy Z. Tausky and Lynne D. DiStefano, Victorian Architecture in London and Southwestern Ontario: Symbols of Aspiration, University of Toronto, 1986.

3. Marion McCrae and Anthony Adamson, The Ancestral Roof: Domestic Architecture of Upper Canada, Clarke, Irwin & Co., 1963.

4. Barbara and Paul Kernohan, discussion in September 2007. The Reycraft Home on E1/2 Lot 25, Con. 3 SER is a classic example of one of these poured concrete homes built in the 1870s in the Ontario Farmhouse style. It is now abandoned and awaiting demolition.

5. Dean Hodgson, History of Tile Drainage in Lambton County, Lambton County Historical Society, 2002, p. ii. See the advertisement in 1869 for bricks. The bricks manufactured in and Lambton County are “white” bricks which have a distinct yellow colour. Houses with reddish colour brick are fewer and were probably imported from other areas with distinct red brick, such as Kent County.

Subscribe to this page

Subscribe to this page