From Mastodon to Arrowhead (Prehistory)

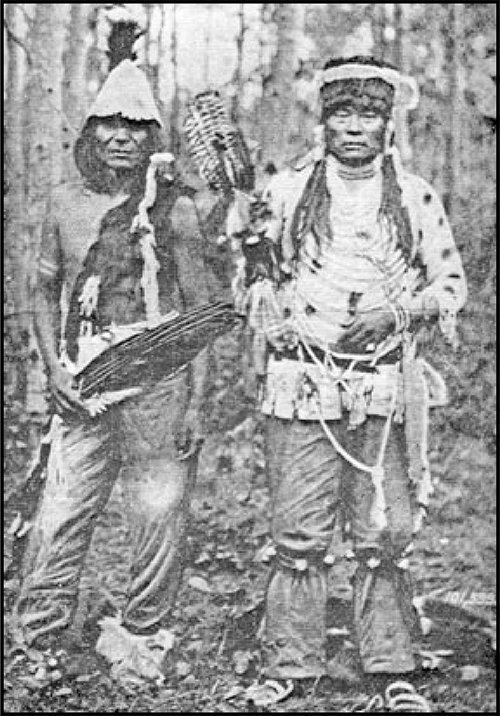

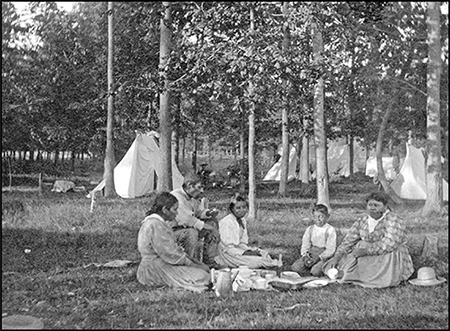

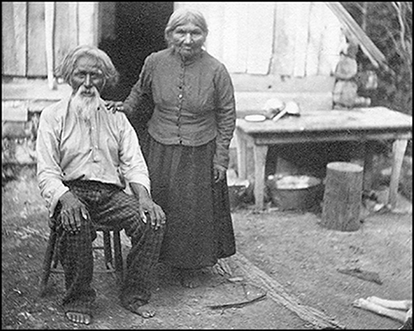

Local Chippewa braves: Note the combination of native- and Western-style clothing and equipment. This was typical of the natives occupying Warwick Twp. in the 1800s. Courtesy of the Lambton Heritage Museum.

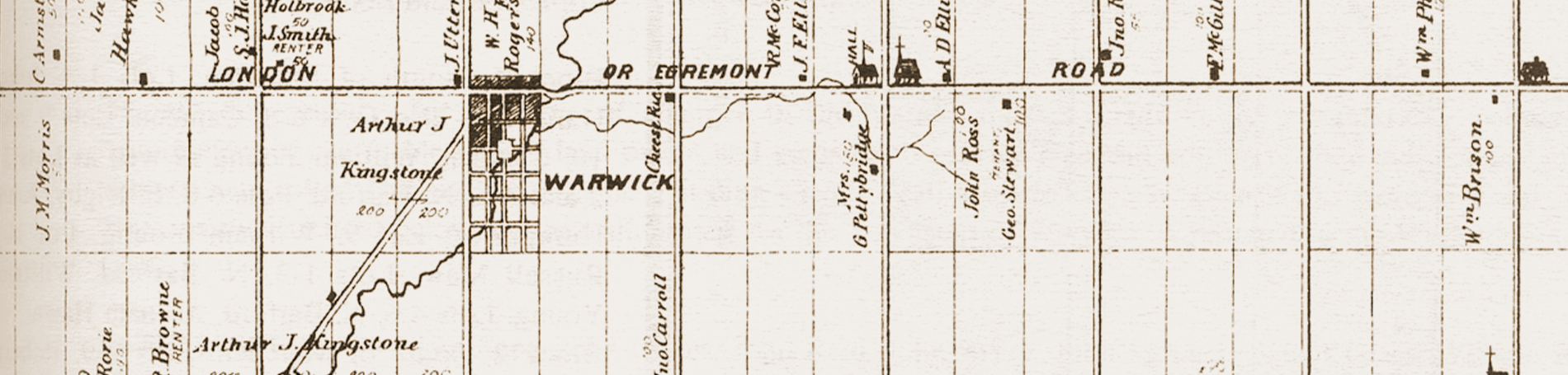

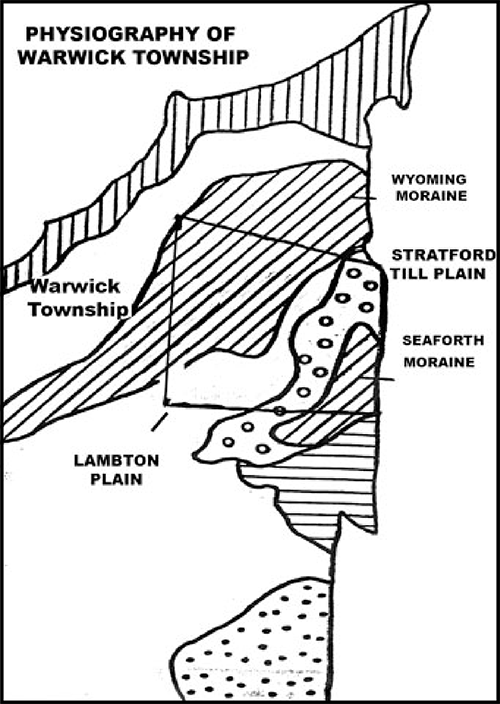

Warwick Township was seasonally occupied by natives for almost 12,000 years. It was, however, never as major a native settlement area as those located around London, Hamilton and Toronto. With its isolated location away from major waterways, Warwick’s main use was as a seasonal location or a travelling route. Th e story of this occupation follows closely the gradual withdrawal of the Wisconsin Glacier which occupied the region about 16,000 years ago. Th e glaciers were often like giant bulldozers which dragged across the landscape, creating piles of mixed earth and stone [known as moraines] wherever they stopped. Th e scraped landscape became lowlands once the glaciers receded,1 creating a poorly drained area with marshes, swamps, hills, rock-strewn glacial plains, large lakes, ponds, and rivers. This region of Southwestern Ontario initially had a tundra-like vegetation, much like the sub-Arctic region of Canada. Over time this evolved into boreal parkland.2 Rising above these areas were the moraines deposited by the retreating glacier. Th e Wyoming Moraine had a major impact on life in Warwick.

Th e Wyoming Moraine had its beginnings northeast of Warwick. It curved in a southwesterly direction through West Williams and Bosanquet Twps. before it touched the northern part of Warwick and headed on through Plympton Twp. on the way to its namesake community, Wyoming. It joined other moraines all the way to Georgian Bay to make a network of highlands which towered above the water-soaked glacial deposits which occupied all the other regions of Southwestern Ontario. Like all highways, this network of hills and undulating landforms made a convenient pathway for the post-glacial animals which occupied our region, barren-ground caribou, bison, mastodons and woolly mammoths being among the more spectacular. As soon as it became possible, these animals utilized these high lands to traverse the region to reach feeding and breeding grounds, located north and south of Warwick, on a seasonal basis.

The region at this immediate post-glacial time was barren ground vegetation with the predominant species of flora being tundra shrubs. Over time, coniferous trees including spruce, pine, tamarack and other water-adapted species gradually transformed the area to that of boreal forest. For the caribou, mammoths and mastodons, the rich tundra-like meadows and conifer thickets proved to be excellent sources of food.3

Paleo People

About 12,000 years ago, the first human travellers, called Paleo people, made their way into the region. These native people were hunters and sought the huge herds of caribou which migrated through southwestern Ontario each spring and fall. The Wyoming Moraine proved to be a reliable source for hunting these animals. Along its winding route several spots for ambush were located. The Paleo people established their temporary camps and, on occasion, burial spots, as they also migrated seasonally through the region. Several of these locations have been identifi ed, not only in Warwick but also in nearby locations such as Bosanquet, West Williams and McGillivray Twps. Th e sites show evidence of weapon repairs, stone chipping, fi res for warmth, cooking and tool making. North of Warwick in Bosanquet Twp. there has also been found a burial site called the Crowfield site.4

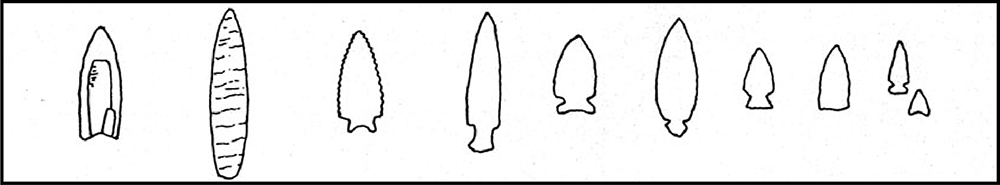

The method of hunting was probably similar to the techniques used in historic times by the “People of the Deer” who lived in the Arctic tundra of the Canadian Shield, an area Warwick resembled some 10,000 years ago. While the giant herds of caribou wandered on the moraine to or from their seasonal homes, the hunters would wait in anticipation of their arrival at a narrowing location where the herd would be crowded together as it crossed over a topographical feature such as a stream or bog or spruce thicket. Disguised in animal pelts, the hunters, grouped as a family unit, would wait for an opportunity to rush the unsuspecting herds as they crowded to go over the location. With their spears they would rush up to the herd and stab as many animals as they could. When a point stuck in or broke off , they simply replaced it and continued thrusting and stabbing. Once the herd had passed, the hunters were joined by the rest of their group — children, women, and older members — to begin the long task of skinning the animals, flaying the flesh, and harvesting the bones, pelts and sinew, which would be utilized not only for food but clothing, tools, shelters, blankets and footwear. Depending on the success of the hunt, this process would take several days or weeks. During this time their camps would be located on the killing grounds. Today, under the surface of these hunting sites can be found a large quantity of stone chips, bone fragments, charcoal and fi re-cracked rocks. Stone artifacts such as points, knives, scrapers, skinning stones and unusual tools called “gravers”5 are also discovered.6

These groups of hunters and their families lived together in small family bands. They faced extremely harsh conditions, as even the summer weather of the region at that time probably remained cooler and wetter than the present day. They faced unpredictable life situations ranging from cold and hunger to physical injury, which may have contributed to controlling the numbers in their bands. Fascinating evidence is still being uncovered about their customs and habits.

With the completion of the harvest and after feasting well, these warriors would move on to another location along the moraine network. They hunted and lived near the animals for centuries, until such time as the climate and vegetation changed significantly. When the animal migration routes changed, the Paleo people also altered their hunting habits. About 6,000 years ago, these people and their animal food sources migrated north out of the region to an area more hospitable to them in a more rugged and colder area of Canada, the boreal forest of the Canadian Shield.

Spear tips: Th e spear points show the progression (left to right) from the Paleo period to the late Woodland period. The two points on the right are probably arrow points. The spear was the basic hunting weapon for most of prehistory. Source: Stone to Steel, Middlesex County Board of Education (MCBE)

Locations of Paleo sites in Warwick are still largely undiscovered. Only in the last thirty years has it been recognized that Paleo people lived in southwestern Ontario. A Collingwood Chert point tip, a base of a fluted point, and a graver were discovered in the 1980s at a site located just south of Arkona along the shore of the former Lake Wittlesey.7 There is some evidence that the Paleo continued to dwell in the region, even as the landscape and climate changed and other nomadic groups known as the Archaic people began to enter the landscape.8

Archaic People

Living in a milder climate reflected dramatically on the lifestyles of these nomadic groups. Th ey relied on a wider variety of animals for their food. They hunted elk, deer, bear, rabbits and a wide variety of birds which inhabited the tall, lush forests of the region. Trees such as walnut, hickory, oak, maple, tulip, coffee, beech, and catalpa occupied a larger portion of the region, including Warwick. Th ese forests also provided ideal locations for flora which served not only to provide the Archaic people with food but also as sources of medicines and the tools which they needed.

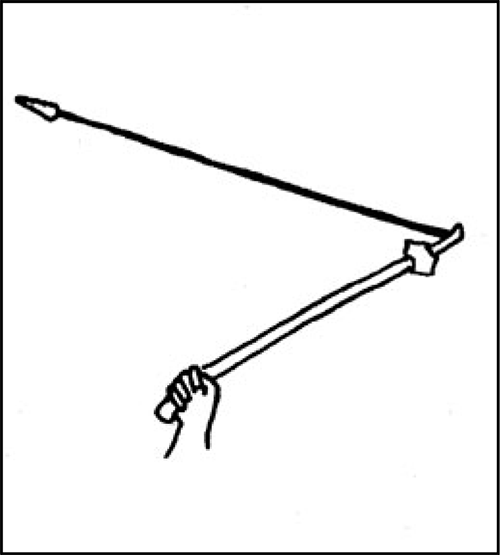

Atlatyl: Th is diagram shows the spear thrower using an atlatyl to launch the spear at his target. It made his throw more powerful and accurate. The atlatyl was given extra weight by the addition of a stone on the shaft. It is thought by some that artifacts such as bird stones and banner stones served this purpose. Atlatyls are still used in South America. Source: Stone to Steel, MCBE

The change in climate encouraged a change in the technology the people used to hunt animals. They found the animals were somewhat faster than those the Paleo had found, and they were no longer able to sneak up and stab their prey. They also found that these animals did not migrate in huge herds so hunting techniques had to be refined to deal with the changes. As a result, the thrusting spear of the Paleo was changed to the throwing spear. An instrument from the southern North American natives called the atlatyl would be fitted on the end of a spear, in essence making the spear thrower's arm 85 centimetres longer. This increased not only the speed of the spear but, with practice, its accuracy. Unlike in the days of the Paleo, finding wood was no longer a problem so pieces could be specifically chosen for spears and atlatyls.9 Points were made from a wider variety of chalcedony found in the Kettle Point area but also imported from as far away as Ohio and the southern United States through extensive trading networks.

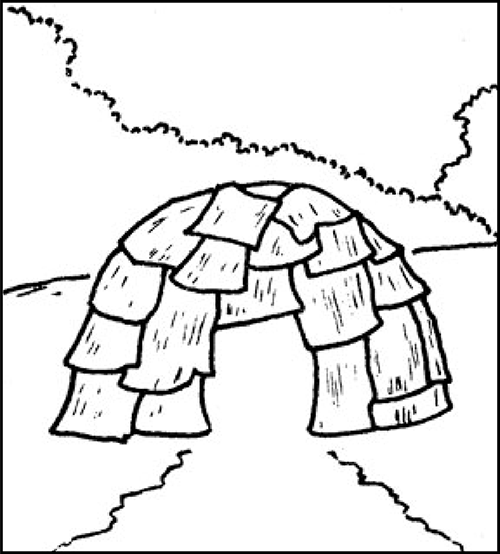

The Archaic people, because they no longer had to follow migrating animals, were able to establish themselves in semi-permanent seasonal habitations. This allowed them to stay in a region to gather fruit and nuts, to hunt, or to fish for longer periods of time. They developed seasonal camps which would consist of relatively permanent domed or cone-like wooden wigwam dwellings made of cedar posts and bark. They probably returned to these locations over a seasonal cycle until the depletion of resources made it necessary for them to relocate somewhere else. 10 Having time to create new tools, these people developed intricate skills, not only in toolmaking, but also in creating artistic items of beauty and skill. Polished stones, intricate ornaments, items made of native copper, as well as a wide variety of spear points found at the sites of their former settlements, all provide distinctive evidence of their skills. The Archaic people prepared for the future by making large leaf-like flint blades with an overall oval appearance. Several of these blades would then be placed in a skin bag and buried in the ground at the site of the seasonal camp. The next time they visited the camp they would have a source of stone to create spear points, knives, scrapers or drills. Early French explorers called these flint blades cache-blades, or hidden blades.

The Archaic people lived in larger groups than those of the Paleo. The relative ease of their lifestyle meant that the dangers of life, although still present, were not as severe, especially during travel and winter. They therefore lived in larger groups or bands, probably between 35 and 50 persons.11 It is speculated by archaeologists that the spring and summer were spent near the lakeshore, and for the autumn and winter they went inland away from the wind and cold.12 These people, in their leisure, produced a plethora of stone tools and artifacts that have been found throughout Warwick Twp. in the past one hundred and seventy-five years. Unlike the Paleo who, because of the nature of their camps and survival, seldom ventured far from the high land, the Archaic were spread out over wide areas near rivers, creeks, high hills and forests, depending upon the nature of their settlement. Warwick, because of its location twenty to thirty kilometres from the lakeshore, would have provided an area for seasonal camping while they g

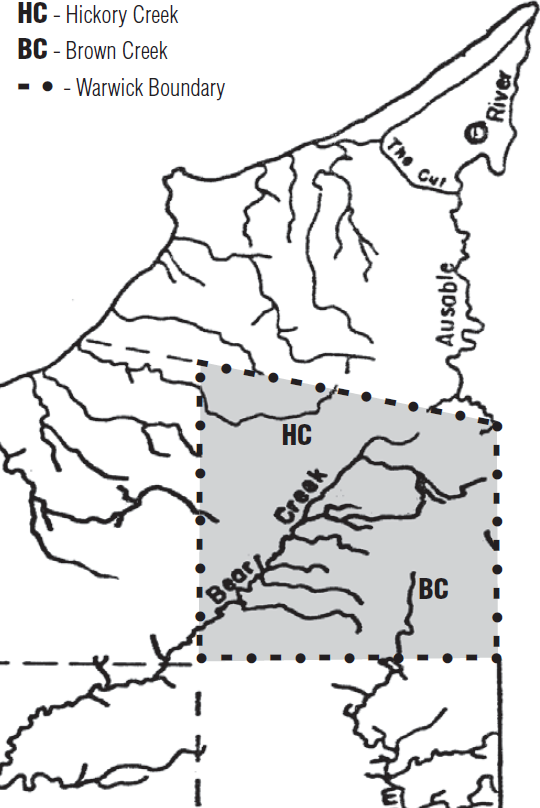

Warwick waterways: Th is map shows the tributaries of Bear Creek, which flow into the Sydenham River system. It also shows Hickory Creek to the northwest and Brown Creek in the southeast. Source: Stone to Steel, MCBE.

Much of the activity of the Archaic people was associated with water, either as camping locations, fishing sources or ambush locations for larger mammals, such as elk, deer, and bear.

The Archaic period is associated with lower levels of water in the Great Lakes.13 Because Warwick is crisscrossed by only smaller tributary streams of the Sydenham and Ausable Rivers, large, abundant sites are not as common as in other locations. However, in 1902, an amazing discovery was made at the Sitter farm in Warwick Twp. when a human skull top was located, with a design carved in it.14 The news of such a discovery made the New York Times and also appeared in archaeological journals of the time.15 That it was from the Archaic period is speculative, but that is the period when many artistic artifacts were created.

There is no doubt that Warwick was the scene of much hunting and gathering by all groups of natives over the past several centuries. Archaeologists have identified three specific periods of Archaic occupation. Th e fi rst is called Early and features a predominant dependence upon the hunting of caribou along with increasing reliance upon deer, elk and smaller animals. It existed until about 8,000 years ago when it became the Middle period. Th e Middle Archaic period, which existed until about 4,500 years ago, showed a dependence upon gathering and fishing. Th e last stage of the Archaic people, called the Late, coincided with the rise in water levels of the Great Lakes, approximately 4,000 years ago.16 These later Archaic people showed a greater dependence on fishing for survival, although hunting and gathering still played a major part in their life.

They either migrated away to warmer climes or adapted to survive in a harsher environment.18

For almost 8,000 years the Archaic bands thrived throughout the region. They prospered in the moderate Ontario climate and forged vast trade routes throughout North America for a wide variety of items such as stone materials, technological devices, different plants and medicines as well as decorative items. Over those years gradual changes began to occur. The climate subtly became cooler, with winters becoming more severe than the natives had previously experienced. The water levels of the Great Lakes also increased to the current modern levels.17 As well, the flora and fauna of Ontario began to change. Soon the Archaic people found that the larger animals they used to hunt had been replaced with faster, smaller, more wary animals, which made their hunting techniques less successful. When lake levels reached the current modern day level, some 2,800 years ago, the Archaic people abandoned Warwick and southern Ontario.

Bark wigwam: Th is simplistic diagram of a bark wigwam represents the early dwelling of the Woodland Indian. When families grew larger, the wigwam became the longhouse of the Iroquoian cultural group. It was the Iroquoians that the first European explorers met. Source: Stone to Steel, MCBE.

Woodland People

After these changes came another group called the Woodland people. The Woodland groups were usually larger and had more permanent living accommodations. Starting approximately 3,000 years ago, these people occupied large portions of Southwestern Ontario including Warwick Twp.19 The Woodland people still relied upon hunting, fishing and gathering for much of their food, but necessity now made them learn about agriculture.

As with the Archaic people, archaeologists have identified three specific stages of Woodland people. The first group was called the Early Woodland. They are identified as having lived in the region until about 2,300 years ago. They were major hunters of deer, and were noted for spring fishing and for harvesting autumn nuts from the trees. Archaeologists state that they existed much as the Late Archaic people did — hunting, fishing and gathering — with very little evidence of horticulture.20 The first vestiges of pottery, which was crude and undecorated, have been found in their campsites along with tobacco pipes and copper beads.21

Th e next group, called the Middle Woodland group, is identified by its decorated pottery. When they arrived in the Warwick area around 2,000 years ago, these people relied heavily upon the hunting of deer, gathering of nuts and much fishing. Th e use of seasonal camps associated with these activities has been discovered by archaeologists. Evidence of the development of agriculture has also been found during this period.22

The major feature of the Middle Woodland people is the increased use of pottery and the development of projectile points. Up to this period the natives relied upon spears and atlatyls to hunt larger game. As the climate warmed, the kinds of animals changed. Smaller, faster animals made an appearance. The spear was no longer as efficient as it had been and was replaced with a new technology, the bow and arrow. The bow and arrow was introduced through trade with South America. Using the wide variety of wood available, with string made from basswood bark or sinew, the Woodland people were able to utilize this tool most effectively. The projectile points used on spears were adapted to be smaller and triangular in shape for use on arrows, and were made from a greater variety of chert types, usually made of local chert found in nearby Kettle Point, from the north shore of Lake Erie or through trade with Ohio and the southern United States.23 Beginning about 1,200 years ago, there appear to have been two distinct groups that occupied Southwestern Ontario. One, which carried on the hunting, gathering, and fishing tradition, was an Algonquin cultural group, called the Western Basin Algonquins by archaeologists. The other, called the Ontario Iroquois Tradition, depended more upon agriculture as well as hunting, gathering and fishing, and may have immigrated into the region in search of more favourable settlements.24

It is speculated that the arrival of the Iroquoian cultural group into Southwestern Ontario led to a marked increase in conflict with the Western Basin Algonquin people. This warfare may have led to the development of palisaded, or walled, villages, more refined weaponry, and body armour. It may also account for the gradual abandonment of Southwestern Ontario by the Algonquin Tradition by the year 1550.25

The last stage of the Woodland people, called Late, came to this area around 1,200 years ago. The Late Woodland people inhabited this region either permanently or seasonally until about 600 years ago. The major features of their culture were the dependence upon the growing of the “three sisters,” corn, beans and squash, and the development of permanent villages.26 From trading with other communities across North America the Late Woodland people learned about planting seeds to grow food which could be stored over time, to be used throughout the year.

This change in lifestyle also led directly to developing implements such as hoes and digging sticks. The corn, beans and squash had to be cooked, which required clay vessels instead of the wood or bark vessels that had previously been used. The clay vessels frequently broke and pottery making became an important pastime for certain villagers. The Late Woodland people made very complex, finely decorated pottery with which they stored, cooked and preserved their agricultural harvests. One of the features of a Late Woodland settlement is the existence of broken pottery shards, often showing intricate designs made by their creators.27

The Woodland people probably lived in even larger groups than the Archaic people. They had to inhabit a permanent settlement which would allow them to maintain their large gardens. The Late Woodland people developed hunting and fishing camps where certain individuals who were good at these skills could spend several weeks or months. The use of nets, spears, fishing weirs, as well as deer fences, traps and other hunting tools demonstrates the technological developments acquired by these skilled individuals.

Perhaps the most striking change in technology, other than agriculture, occurred in the field of hunting. Long gone were the vast herds of caribou or elk that the earlier prehistoric people were able to hunt using spears and atlatyls. Animals such as white-tailed deer, rabbits, beaver, squirrels and game birds required a much faster technology than the spear. The spear was still used, but, like other old- fashioned tools, fell into disuse over time, as the bow and arrow became more popular.

The main villages of the Woodland people varied in size from about one hundred people to over a thousand, living in long bark homes which the first Europeans called longhouses. A small hamlet may have had two or three longhouses, such as the reconstructed village of Ska Nah Doht at Longwoods Road Conservation Area near Mount Brydges.28 Fields of several hundred acres surrounded the village. Some villages, such as the Lawson site near London, consisted of several dozen longhouses and probably held over a thousand people. Th ere is little evidence that any of these large villages existed in Warwick during this time period. Indeed, because of the nature of Warwick’s clay soil, this area may not have been conducive to such an agriculturally-based culture. Warwick may have been used for seasonal hunting, fishing and gathering expeditions by Woodland groups, including the Iroquoian group.29

Madam Mindiski, 1898: Note the bark shelter and the pipe smoking. Tobacco was and is considered sacred medicine. Source: Talman Regional Collection, UWO.

Tobacco became a very important cultural feature of the Woodland people. It was used as a medicine and as a mind-expanding drug, and through its use clay, stone and corn cob pipes evolved. It was a valued trade item with other groups across Ontario and afar. To this day, tobacco is honoured by the native people as a sacred plant with very special uses and spiritual meanings.

With the coming of Europeans to North America, the life of the aboriginal people changed irreparably. The most significant effect was the introduction to the natives of European diseases such as smallpox. A huge number of natives who came in direct contact with the Europeans became infected and countless thousands died.

Following a war of approximately 50 years, encouraged by France and England, the Algonquin (Chippewa) Nation who lived in the northern portion of Ontario managed to drive the Five Nations Iroquois people from Southern Ontario. Subsequently, by early 1700 the Algonquin people began to settle the area. The oral legends and stories of the Algonquin culture include tales of the conflict with the Iroquois.30 These people may have been the descendants of the Western Basin Algonquins who had been forced out by the immigration of the Ontario Iroquois Tradition 500 years earlier.31 They were hunters, fishers and gatherers, and therefore nomadic in their lifestyle. It was these groups of people that the first European settlers of Warwick met when they settled the land.

Following the arrival of the French in the Detroit and Lake St. Clair region in about 1700, Warwick would have been visited by fur trappers and natives who used the area both as a source of animals to hunt and trap, and as a route to and from the lakes. “Indian trails” which crossed the region often led to the chert beds at Stoney Point, which served as a source for their stone tools.

As European trade and its introduction of metal tools, implements and decorations to the natives increased, the demands for chert diminished considerably. As a result, the nomadic bands of Algonquins set up camps throughout the area to carry out their traditional hunting, fishing, gathering and wintering. Warwick, as seen by the early pioneers, was an area used by small bands of these natives.

After the American War of Independence and the Treaty of Paris in 1783, the British government had to find homes for its Loyalist refugees from the United States. From 1780 to 1830, they signed a series of native land treaties which saw the natives of Ontario surrender large tracts of land to the government in exchange for treaty payments and a series of “reserves” set aside in which the natives were to live.

Many of these treaties are being questioned today and have continued to cause conflict in Ontario, as well as the rest of Canada.

Th e surrendering of the land in Warwick occurred officially with the signing of Treaty No. 25 in 1822 with the Algonquin Cultural Group.32 When the first European settlers began to move into Warwick Twp., they encountered bands of natives who still used the vast wilderness areas for their food and shelter. For many years these two cultures managed to coexist with very little conflict, since the settlers were dependent at times upon the skills and expertise of the natives for hunting and fishing, gathering of natural foods or knowledge of the environment. In return, the Europeans provided the natives with needed shelter in times of storms, medicines and medical treatment, and often use of their property for temporary camps.33 Warwick residents appear to have had a tolerant relationship with the natives but gradually, as the wilderness aspect of Warwick shrank, the native bands moved to their reserve lands at Sarnia, Kettle Point, Stoney Point, Muncey and Chippewa of the Thames.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, most direct social intercourse with natives by the Warwick residents ceased. Th e land had been cleared of much of the natural forest cover, fi elds were fenced and modern farm buildings had been erected. Warwick was no longer a hospitable environment for the two cultures to interact. Gradually, the presence of the First Nations people diminished from the developing Warwick landscape as they withdrew to their lands on nearby reservations.

Endnotes

These links were used at the time of publishing in 2008. Some links may have changed or may no longer be active.

1. Ontario Archaeological Society, “Post Ice-age Geography and Environment,” https://ontarioarchaeology.org/resources/summary-of-ontario-archaeology/ accessed January 3, 2008.

2. Michael Troughton and Cathy Quinlan, A Heritage Landscape Guide to the Thames River Watershed, unpublished manuscript, 2006, p. 51.

3. Ontario Archaeological Society, “First People of Ontario: The Paleo-Indians,” https://ontarioarchaeology.org/resources/summary-of-ontario-archaeology/ accessed January 8, 2008.

4. J. V. Wright, Ontario Prehistory: An Eleven Thousand-year Archaeological Outline, National Museum of Man, Ottawa, 1972.

5. A graver is an index tool associated with Paleo sites, although its exact use is still unknown.

6. Dr. Brian Deller, conversation, 1990.

7. Chris Ellis and Neal Ferris ed., The Archaeology of Southern Ontario to A.D. 1650, London Chapter OAS, 1990. Brian Deller and Chris Ellis, Occasional Paper No. 5 “Paleo-Indians”, pp. 41–42.

8. Troughton and Quinlan, p. 52.

9. Deller. See also From Stone to Steel: A Historical Guide to People, Events, & Places in Middlesex County, Middlesex County Board of Education, 1979, pp. 9–10.

10. Ontario Archaeological Society, “The Archaic Period,” https://ontarioarchaeology.org/resources/summary-of-ontario-archaeology/ accessed January 8, 2008.

13. Troughton and Quinlan, p. 52.

14. Toronto Globe, “Indians' Bones Found,” Aug. 8, 1902, p. 2.

15. New York Times, “Perforated Indian Skulls,” Aug. 10, 1902, p. 2.

16. Ibid. See also Ontario Archaeological Society, “The Archaic Period”, for more detailed information.

17. Ibid. Troughton and Quinlan state that the Great Lakes reached current water levels about 4500 years ago.

18. Neal Ferris, an archaeologist from UWO, operated an archaeological dig early in 2000–2001 on the late Casey Bonger’s farm in Warwick. It was an Archaic site and would be destroyed by the expanding gravel pit located on the farm. Th ere also was a burial site dig located on the Utter farm, east of Arkona, in the late 1980s.

19. Ontario Archaeological Society, “Early Woodland Period,” https://ontarioarchaeology.org/resources/summary-of-ontario-archaeology/ accessed January 3, 2008.

20. Ibid. They speculate that these people may have grown squash and gourds to be used as containers for their seeds, nuts, and berries which they gathered.

21. Ibid. See also Troughton and Quinlan, p. 54.

22. Troughton and Quinlan, p. 54.

23. Ontario Archaeological Society, “Middle Woodland Period,” https://ontarioarchaeology.org/resources/summary-of-ontario-archaeology/. accessed January 3, 2008. This is a very complex subject which cannot adequately be covered in a few lines. For more information and detail consult the above source as well as Chris Ellis and Neil Ferris, The Archaeology of Southern Ontario, Museum of Indian Archaeology, London, 1985.

24. Ontario Archaeological Society, “Late Woodland Period,” https://ontarioarchaeology.org/resources/summary-of-ontario-archaeology/ accessed January 3, 2008.

26. Troughton and Quinlan, p. 54.

27. Ontario Archaeological Society, “Late Woodland Period,” https://ontarioarchaeology.org/resources/summary-of-ontario-archaeology/ accessed January 3, 2008.

28. W. J. Wintemberg, Lawson Prehistoric Village Site, Middlesex County, Ontario, National Museum of Canada Bulletin #94, 1927.

29. The late Ted Baxter, a former resident of Warwick, spent a number of years surface hunting around the Arkona area, looking for native artifacts. He found hundreds of artifacts including a large ceramic pot which he reassembled; it is on display at the Arkona Lions Club Indian Artifacts and Fossil Museum at Rock Glen. He found it on a sandy knoll on the current site of the Arkona Fairways Golf Club. As ceramic pottery was particularly associated with Late Midland period, it is possible to speculate that they would have ventured into the Warwick region as well.

30. See G. Copway, The Traditional History and Characteristic Sketches of the Ojibway Nation, Prospero, 1850 (2001), pp. 87–89. This is a very dated book but draws from the oral traditions of the Natives to outline the events of the past.

31. Ontario Archaeological Society, “Late Woodland Period,” https://ontarioarchaeology.org/resources/summary-of-ontario-archaeology/ accessed January 3, 2008. This is a fascinating area for future study by historians, and archaeologists.

32. Troughton and Quinlan, p. 62.

33. See entries from the diary of Peter Alison, recorded in 1903.

*The OAS revamped the website in 2017 and all links originally used/sourced are now on one page. Link for endnotes 1, 3, 10, 16, 19, 23, 24, 27, 31 is now https://ontarioarchaeology.org/resources/summary-of-ontario-archaeology/

Chapter 2 of 25

Subscribe to this page

Subscribe to this page