St. Clair Borderers (Military pre-World War I)

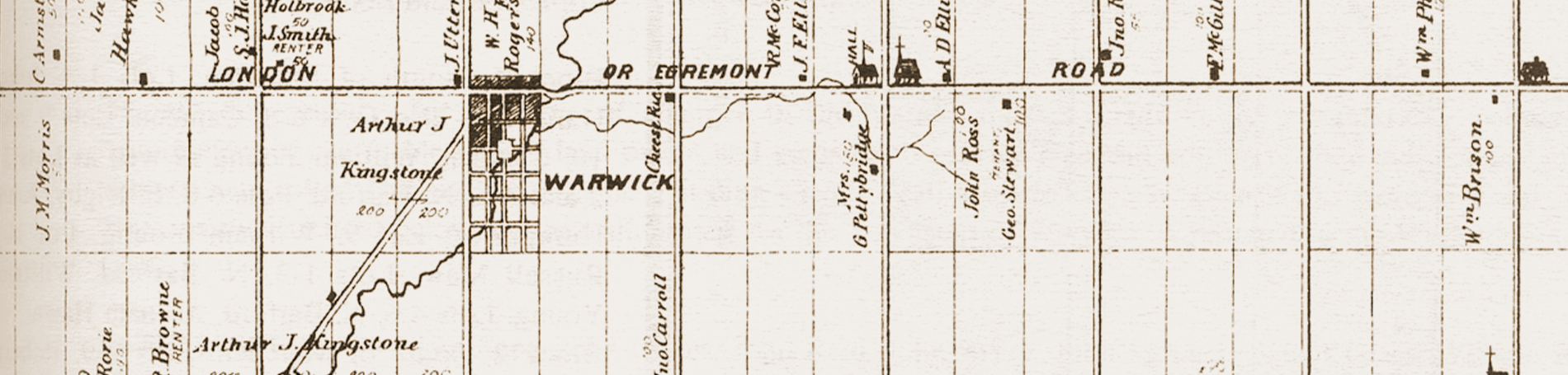

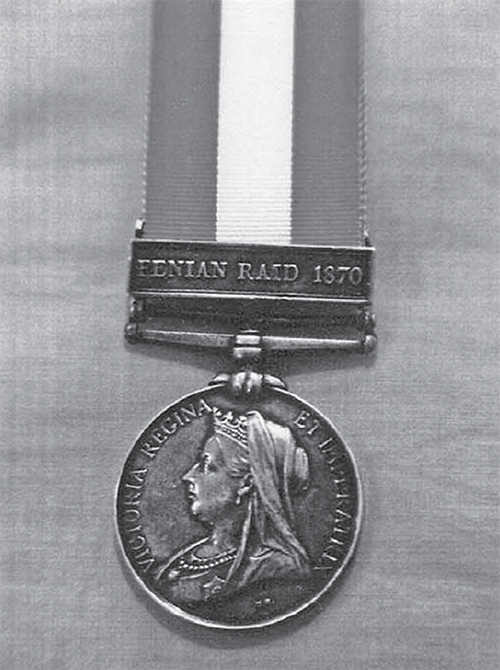

Watford Fair Grounds Crystal Palace: The Warwick Drill Hall was built in Village in 1837. It was later moved to Watford where it became the Crystal Palace at the Watford Fairgrounds until it was destroyed by fire in 1926. Courtesy The Guide-Advocate.

by Glenn Stott

Rebellion of 1837

The background of many settlers was military, as a large portion of them had left the army and received land grants as a reward for their service during the Napoleonic Wars (1796–1815).Their military expertise may have been called on within about five years of the survey of the township, in December, 1837 with the Rebellion of Upper Canada led by William Lyon Mackenzie (1795– 1861). Mackenzie's revolt focused on the Toronto area, at the site of Montgomery's Tavern, which is now the site of Postal Station K on Yonge St. near Eglinton. In 1837 this was the rural area of York County. The Rebellion failed miserably and Loyalist troops scoured the area looking for “rebels.”

In the London and Western Districts, of which was a part, another leader, Dr. Charles Duncombe, led a group of “rebels” to the village of Scotland in Brant County. They were to join with Mackenzie's group and seize control of Toronto, because all British troops had been dispatched to Lower Canada (Quebec) to put down the violent uprising there, leaving no troops in Toronto or Upper Canada.

Rebellion of 1837: Dissaffected “radical” reformers seeking Responsible Government (whereby the Executive Branch of the colonial government was responsible to the elected members) felt that the existing legislative system was not working, mostly due to the intransigence of the local and provincial oligarchies. The Family Compact and Lieutenant Governor Sir Francis Bond Head jealously guarded their power, fearing that the reformers were opening the door to Americanization, or even worse, annexation to the United States. Since working through the constitutional or legal framework showed little hope for change, the radical reformers -- always a small minority in the colony -- resorted to armed insurrection led by William Lyon Mackenzie at Toronto and Dr. Charles Duncombe in the vicinity of Brantford. While the Rebellions in Lower Canada were a serious military threat, the Upper Canada rebellions were easily crushed. The Rebellions seemed to be a triumph of the old Tory oligarchy, but at the same time caught the attention of the Imperial Government. They led to the unification of Upper and Lower Canada and, ultimately, after much political debate and compromise, Responsible Government was enshrined in 1848. SOURCE: Dr. Greg Stott.

Duncombe assembled the group on December 7, 1837, with the intention of joining Mackenzie in Toronto on December 10. For some reason, Mackenzie decided to make his move to seize the capital of Upper Canada three days earlier. Word reached Duncombe that the rebellion had been defeated, and indeed Loyalists under Sir William McNab were headed to Scotland to arrest and destroy the London District Rebellion. Duncombe, realizing the “jig was up,” urged his men to disperse and go home. Many of the 500 assembled did just that, but several made their way to the United States, where they carried on their activities to overthrow the Government of Upper Canada.

In Twp. most of the men were busy simply trying to survive. Nevertheless, all males of between the ages of 16 to 60 were considered as being suitable to serve Queen Victoria and were put on the militia roll. In all the British colonies, June 4, King George III's birthday, was a traditional militia training day and everyone on the militia muster roll was expected to turn out or be fined. It is safe to say, however, that one day of drill, with or without weapons, would not make the militia combat-ready.

With 's isolated situation it is doubtful if any of the militia were actually called out during the rebellion. There is only one document which records the names of the militia who were on the muster roll from February 1 to February 28, 1838, a time when the border regions with the United States would have had extra guards.1 Therefore it is possible that the militia actually did active duty during the month of February 1838, perhaps at Port Sarnia or Errol, to prevent incursions by rebel forces from the United States. By the record it appears that Major Freear and Captains Burwell and Joseph (Uncle Joe) Little did the full 28 days of service while the remaining 91 on the list were paid for four days' duty.

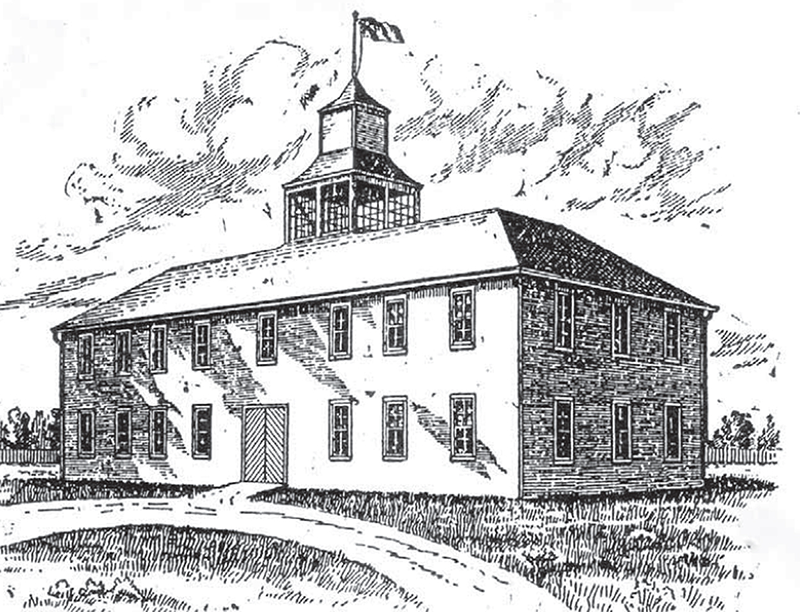

Freear (Freer) medal, sword and pistol images: Colonel Freer served with the Duke of Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. His sword, medal and flintlock pistol from that battle are on display at the Strathroy Museum. Source Strathroy Museum.

The Western District, of which Lambton was a part, was the scene of a raid in Dawn Twp. on June 27, 1838, where Loyalist troops attacked a house. In the incident, a militia officer, Captain Kerry, was shot and killed by a rebel, William Putnam. The Rebellion of Upper Canada lasted until the early 1840s with the Battle of the Windmill near Prescott in November, 1838 and the Battle of Windsor in December, 1838.2 A number of rebels were captured and imprisoned. After these two events and a number of minor incidents along the border, the captured rebels were tried throughout the colony. Several rebels were hanged, including six at London in February, 1839. Others spent months in prison but were pardoned by Lord Durham upon his arrival in Canada in 1839. At least one of the men captured in Dawn Twp. was transported to Van Diemen's Land, (Tasmania).3 Van Diemen's Land was used by the British as a penal colony to punish criminals harshly.

A Ludicrous Scene at a Military Funeral: Recollections of Con. Ragan The following sketch was written at the earnest request of Mr. H. M. Carroll, now of this place, who was present, and can vouch for the descriptive accuracy of the scene described:— In the early part of the spring of 1845, there died a worthy Col. of the Militia named Freear [commonly called Col. Freear] on the lot adjoining the Village of Warwick. The Colonel had in former years served as an officer in the British Army, consequently, his services were brought into requisition during the years 1837–38, or during the rebellion of those times, when he displayed a good deal of military ability and usefulness. He was also a J.P. and a commissioner in Courts of Requests. He built a grist-mill, which however, proved a failure, was a man of kind and affable disposition, a thorough Irish gentleman, but he was compelled to pass in his cheques. The scene at the funeral was so ludicrous that it made such an impression on my memory that it never has been effaced. In fact, I see the whole in panorama shape passing in my mind now as vividly as the day on which the event took place, more especially did it interest me having witnessed military funerals in the city of Dublin and in the city of Toronto a short time before. On the day previous to the funeral, as many of the militia as would form an escort and fi ring party were dutifully notified to attend. Major Ingles, being the next senior officer in command, took charge of this most important duty. It must be observed that we had no volunteers with cap shacks, & c., in those days, no Snider Enfield rifles or other modern weapons of warfare. Imagine then each militia man coming dressed, as his means or fancy would admit, some with the common straw hat, some with an old dilapidated plug, a little flattened down, to be sure, but then, that same hat was once new and stylish, some with caps, and as for coats and un mentionables, a good number resembled Joseph’s coat of many colours, with particles of every imaginable colour and material, as for shoes, some had one boot and shoe tied very neatly with some basswood bark, some of the men had evidently shoved their legs too far through as their exposed nether part of their legs was plainly visible. Major Ingles, who by the way was a perfect specimen of military gentleman, at the house previous to starting, had selected his fi ring party, who had every kind of weapon, from the small Indian fowling-piece of all grades and calibre to the bold Elizabethan musket. Having given the men every verbal information as to how they should prime, load and fi re at the grave, the order was given to march to the cemetery at the Village, which was done something in the following order. First, George Clark [who had formerly been in a band in the regular army] about six rods ahead, walking and playing an appropriate dirge, the Portuguese Hymn, I think, with a clarinet, next, Major Ingles, dressed a la militaire, with a suitable coat, cap, sash, & c., with drawn sword in front of the fi ring party, with arms reversed or partially so, then the defunct Colonel carried on a bier [there was no hearse to be had in those days] next the multitude, as motley a group as can well be imagined. Service was read by the Rev’d Mr. Mortimer, at an old log school house, when the procession again started for the graveyard, a stone’s throw from the school house. The services of the clergyman being through, Major Ingles, who had evidently been looking at somebody drinking that morning, with sword in hand, commanded the fi ring party to take their places, and with stern voice gave the words prime, load, ready, present, FIRE! And now, let me describe the fi ring. Anyone who has witnessed the fi ring of a volley at the grave, knows that there should be but one report; not so in this case, in fact, I can only describe it this way: Imagine a piece of picket fence, with some boy to run along the side with a stick in contact with the pickets, then some idea may be formed of this irregular firing, but the climax had yet to be reached. Someone of the party had reserved his fi re until the last, and being a musket of large calibre, made a deafening noise. The gallant Major Ingles, who was by this time exasperated at the fi ring, stepped boldly to the front of the grave and with stentorian voice, made the following remark, “Who the devil fired that last shot?” Thus ended one of those amusing reminiscences of early days. I may state, however, that the services of Mr. Clark and his clarinet were engaged for the evening at Nixons and those who missed the wake, made up for sport to equal it that night. P.S. I have since learned who fi red that last shot — Thomas Kenward. SOURCE: Watford Guide-Advocate, May 2, 1879.

Militia

's population, because of its British military background, appears to have consisted mainly of loyal citizens. Thomas Speers, Crown Land Agent for the Western District, noted that Twp. residents were settlers whose loyalty to the Crown “cannot be surpassed and in few sections of the country can't be equaled.”4

By 1842 the threat of invasion by the rebels had been diminished in the Western District. The militia no doubt still met every June 4 for its muster day held at the drill shed in Village. The parade grounds and target ranges were located to the east of the village on the Bear Creek flats.5

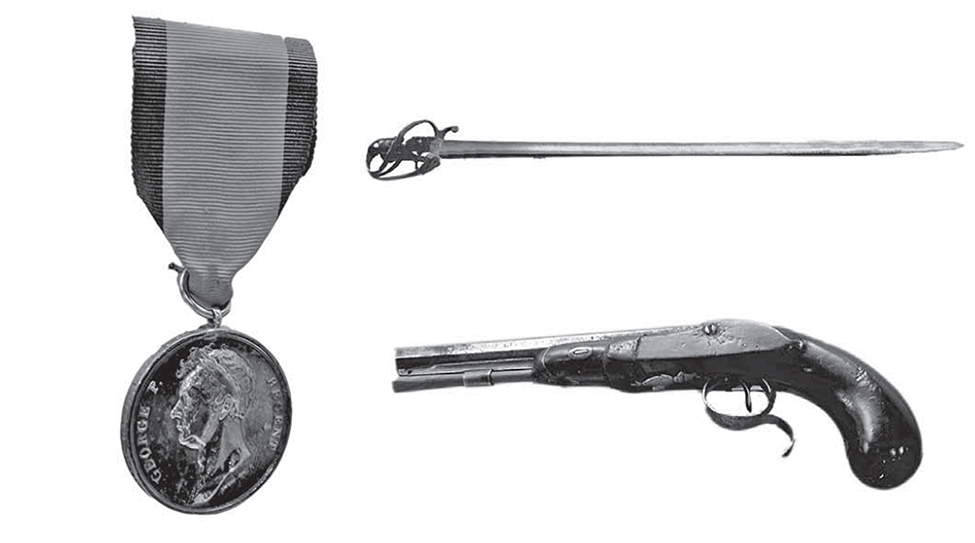

Medal struck for veterans of the Fenian Raids: Following the Fenian threat of 1866–1870, soldiers who served in the Canadian militia on active service such as border patrol received this medal. Courtesy P Evans.

Generally the militia lacked proper uniforms and weapons. Usually only officers had a uniform and sword. The militiamen were expected to bring whatever weapon they owned and suitable clothing to be of service when called upon. During the rebellion, Loyalist troops wore a distinctive armband to identify them as Loyalists. Their weapons would have ranged from rifles, flintlock and percussion muskets to pitchforks, shovels and homemade clubs.

The next incident which focused on the militia was the military funeral of the Colonel of the militia, who died after falling off a horse in the spring of 1845. Colonel Arthur William Freear was a Captain under the Duke of Wellington who fought in the Second Battalion, 50th Foot Regiment, who fought under the Duke of Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo. Following the war, Colonel Freear was sent to Ireland as part of the Occupational Forces. In 1831, with a grant of land being given by the crown to encourage settlement in Canada, Colonel Freear accepted two hundred acres of land near Village, where he established a saw and grist mill on Bear Creek.

American Civil War

The next call for active militia duty was when the American Civil War broke out in 1861. Britain's role was to supply the Confederate States with munitions and other military equipment. Tension increased between Britain (including all the colonies in North America) and the United States. As a result, additional British troops were dispatched to Canada.6 All males living in each District were classified according to their age for future militia duty if necessary.

Fenian Raids

A group of dissident Irish, called Fenians, had taken form in the United States as early as 1857. They advocated an invasion ofCanada to obtain liberty for Ireland from Great Britain. Many of the soldiers who served in the United States were Irish immigrants who favoured such an effort. As a result, American Fenian Brotherhood groups began to form in many of the border cities in the United States, without much interference from the United States government.

Phantom Fenian – An Amusing Warwick Incident: Your article “Crossing the Line”, about the Fenian troubles of the nineteenth century (Feb/Mar, 1999), reminded me of a story about my great-great-grandfather, Robert Fleming. He, with his new bride, Elizabeth Allison, had settled in Township in what is now southwestern Ontario, in the early 1800s. This was near the U.S. border of Detroit. Worried about possible Fenian raids, he woke one night upon hearing a noise. He ran to look out in the yard and saw something moving. He immediately got his gun and shot at the movement he thought was a dreaded Fenian, only to fi nd later that it was his own long underwear waving in the night breeze. It had been hanging out to dry and he had forgotten at the end of a busy day. The Fenians never did trouble them again. SOURCE: Women’s Institute Tweedsmuir History Books. Original letter by Kathleen Kemp Haynes of Dorchester, Ont., was printed in “The Beaver”, Canada’s History Magazine, date not recorded.

By the spring of 1866, over 30,000 Fenians were gathered in several border towns along the American- Canadian border, threatening to invade Canada. The Government of Canada (Canada East and Canada West) called up 20,000 militiamen to duty.7

There were two major incidents involving the Fenians in Canada. The first was in New Brunswick. It ended with intervention by the British Navy, the militia and American authorities who seized much of the Fenians' munitions and equipment. The second and most serious invasion occurred in June, 1866 in the Niagara area at the Battle of Ridgeway, where Fenians managed to defeat the Canadian militia but withdrew back to the United States.

Unfortunately there is no written record of a third incident, or even mention in any period resources. Some older residents told of there being an incident in the Aberfeldy area where a group of Fenians managed to infiltrate. Regardless, the residents of southwestern Canada West, including our area, were stirred up in March 1866 by rumours and speculation about imminent Fenian attacks.

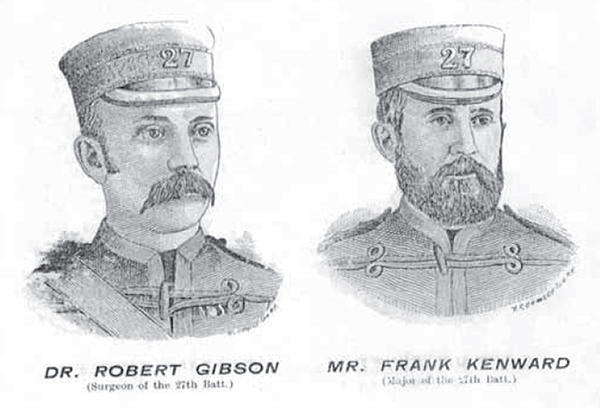

Dr. Robert Gibson and Major Frank Kenward: Th e three companies of the St. Clair Borderers from the area were part of the 27th Lambton Battalion of Infantry. Dr. Gibson and Major Kenward were officers of the Battalion headquartered at Sarnia. Courtesy Forest Museum.

There were a few other incidents, looked upon today as minor, but in the hearts and minds of the citizens living in , the threat of an invasion by the Fenians was enough to strike fear and dread. One might equate it to the fear of terrorist attacks following September 11, 2001.

There are few records of the service done by the militia during these times, but Fenian Raid medals were given to some of 's residents who must have done garrison duty along the border regions throughout the time of threats.

St. Clair Borderers

In 1866 Canada was organized into 18 military districts. Lambton County was responsible for the 27th Lambton Battalion of Infantry, called the St. Clair Borderers.8 The battalion's headquarters were in Sarnia when it was organized into eight companies on September 14. The Infantry was Number 5 Company. Number 7 Infantry Company was organized in Watford, and the Artillery Company was the Number 8 Company out of Sarnia. Forest was assigned Number 2 Infantry Company in 1873.9

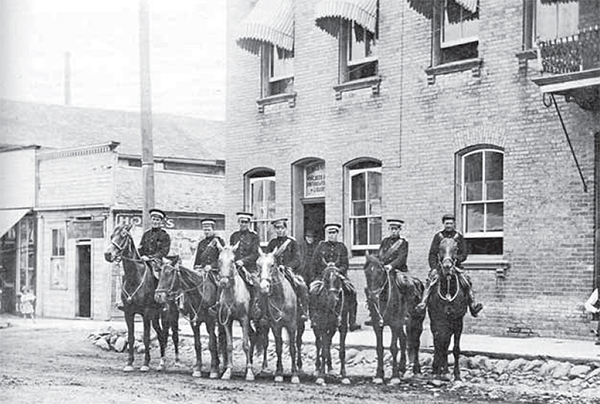

27th Regiment in front of Roche House: A small mounted detachment of the militia show the wide variety of uniforms and accoutrements which were distributed to the members. Courtesy G Richardson.

The Lambton Battalion carried out regular maneuvers at various locations, including Carling Heights and Wolseley Barracks in London. By 1871, because the British army had withdrawn all of its troops from Canada, the militia battalions had a more active role to play than ever before.

The Northwest Rebellion of 1885, or Riel Rebellion, caused a stir among the militia, but the Lambton Battalion was not called out to active duty. The soldiers still conducted drill parades one day per year. Special training sessions of 10 to 12 days each year were held by the regular officers from the Army base in London, Ont.10 Some of the training areas were located in the former British training area along the Thames River, outside of Komoka. Widder Station in Bosanquet Twp. later became a training centre for militia.

From newspaper articles of the time there appears to havebeen a continued keen interest in military affairs in and area. When inspected, the St. Clair Borderers achieved

first place among several other battalions in 1898 and Lt. Colonel Maunsell, the Government Inspector, said the 27th was the “best rural battalion he had ever inspected.”11 On May 5, 1900, the name of the Lambton Battalion was simplified to be the “27th Lambton Regiment, St. Clair Borderers.”12

Soldiers in Arkona, 1916: A route march (a specified training route) of the 149th Lambton Battalion through the streets of Arkona from Camp Widder near Thedford was part of the regular military training of World War I. The soldiers in the front column are shouldering the infamous Ross Rifle while the others have not been issued arms. (Although accurate, the Ross Rifle had serious problems, including failures to extract a fired case, constant jamming of the bolt due to field debris, and bolt blowback. Many troops were killed by the enemy while attempting to clear malfunctions. It was withdrawn from service during World War I.) Coutesy R Dunham collection.

With the arrival of World War I in 1914 the Lambton Regiment became a supply regiment which sent recruits to serve with 149th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) and later the 70th Battalion of the CEF. Widder Station continued to be a training centre for militia and regulars during World War I and up until the establishment of Ipperwash Military Camp in 1942. Soldiers from Lambton served with others from all over Ontario and Canada throughout the war. As casualties mounted, recruits were sent to whatever battalions required replacement soldiers.

In 1920, the 27th Battalion became simply the Lambton Battalion.13 Just before the outbreak of World War II, on December 15, 1936, the Lambton Battalion was broken into three different groups: the 26th (Lambton) Field Battery of the Royal Canadian Artillery, the 11th (Lambton) Field Company of the Royal Canadian Engineers, and the 1st (Lambton) Field Park Company of the Royal Canadian Engineers.14

's military history started with retired military men coming to settle as pioneers with their families. It continued during uprisings in both Canada and the United States. The tradition continued in World Wars I and II when both our men and women served to fight for their country and for freedom. It continues today.

Endnotes

These links were used at the time of publishing in 2008. Some links may have changed or may no longer be active.

1. Public Record Office of London, England, MG 13, W.O. 13, Reel B- 3194, Folio 7. This list has been recorded by the Lambton Branch of the OGS. Many of the men on the roll were from Brooke Township.

2. See Colin Read, The Rising in Western Upper Canada, 1837–1838, University of Toronto Press, 1982, and E. C. Guillet, The Lives and Times of the Patriots, University of Toronto Press, 1968.

3. Read, pp. 145–146. See also Guillet, p. 276. There were a total of eleven Western District residents who were arrested during the Rebellion.

4. Thomas Speers, Crown Lands Agents' Record concerning the settlement of Adelaide, Metcalfe & Townships, Chatham, June 30, 1840, PAO, RG1-605-0-4, p. 4.

5. The drill shed from Village was later moved to Watford, where it was located at the Watford Fairgrounds and called the Crystal Palace.

6. J.A. Foster, Muskets to Missiles: A Pictorial History of Canada's Ground Forces, Methuen, 1987, p. 50. Foster says that in 1862, Britain had a total of 18,000 troops in Canada.

8. A battalion was made up of about 1,000 men (maximum enrolment) formed into 10 companies of about 100 men each. “Regiment” was the name given to a particular army unit. A regiment could consist of several battalions. An example would be the Royal Canadian Regiment, which consisted of four battalions. See Foster, p. 49. See also http://www.regiments.org/regiments/na-canada/volmil/on-inf/027lambt.htm accessed August 14, 2006.

9. See Forest and District Centennial, Forest 100 Years, 1888-1988, “No. 2 Company 27th Lambton Regiment ‘The St. Clair Borderers'”, 1988.

11. Forest Free Press, “Volunteers Home Again”, June 23, 1898.

12. http://www.regiments.org/regiments/na-canada/volmil/on-inf/027lambt.htm accessed August 14, 2006.

Subscribe to this page

Subscribe to this page