Recollections and Reflections (Miscellaneous Memories)

Life in a what is often referred to as a simpler time: William and Annie (Tanton) Waun in front of their home, the north part of Lot 18, Con. 1 NER (home of the Bill Trenouth family in 2008) Carter & Isaac photo, 1910-11. Courtesy D Aitken.

compiled by Glenn Stott

Anderson Family

(Ella Anderson Atkins’ story, as recorded in 1976 or 1977 in Warwick WI Tweedsmuir History Book 4)

[Ella Anderson was born in 1889 to Harriet (Sullivan) and Peter Anderson. She lived on 18 Sideroad (Nauvoo Rd.).]

I (Ella) attended school in SS# 5. Dave (D.A.) Ross was my first teacher, followed by Nelson George and Ernie Truman. When I first started to school and became very weary, Mr. Ross nursed me on his knee while he continued teaching the other classes….

My father, Peter Anderson, son of Robert and Margaret Anderson, bought the farm where we all enjoyed our early days, from a Mr. Stewart, about 1882. My father started as an ordained Methodist minister in Cobourg. He was educated at Victoria University. He preached for some time in London Township, where he rode on horseback to his churches and paid tollgate fees. He enjoyed his ministerial life, but he had some kind of throat trouble and he had to give that up. He then taught school in the one-room schools of Warwick. He loved teaching and followed his various pupils all through their lives. Some became noted statesmen and gave helpful service in many ways of life. The chalk dust bothered his throat and he had to give up teaching. He then bought the farm [where I was raised].

We attended Bethel Church, nearly five miles northwest of our farm. We went to church rain or snow. It was a long service — Sunday School at 1:25, Church at 2:30 with Class Meeting after that. I still remember how tired I got. I had a little round basket with a lid that was filled with cookies that I took to church. One Sunday in wintertime I fell asleep coming home and the basket fell out on the road. When we arrived home I missed my beloved basket and I cried and said I wanted to take it to heaven with me; now it was gone. Father turned around in the deep snow and went back some distance and came back with my basket, smiling and as happy as could be. He was always happy, never cross, and loved us all. If things did not always go just right he would say, “We will try it some other way.”

Audrey Beattie: Bus Driver

(from The [Sarnia] Observer, Jeff Hurst; Nov. 16, 1991)

Retirement seems to sit well with Audrey Beattie. The lifetime Watford area resident was raised on a farm, but is even more prone to a workhorse lifestyle at the age of 66. Since retiring and selling the farm, Mrs. Beattie began driving a school bus as a favor to a neighbor.

That was 20 years ago, and now she shares regular shift driving duties with husband Patten.

“It’s been a pleasant experience for both of us,” explained Mrs. Beattie. Initially she was scared to death about driving, but soon warmed to the idea. She said driving through the countryside watching the seasons change is a relaxing time for her. Though some big city bus drivers may have problems with secondary school students, Mrs. Beattie says her experience in Watford has been positive….

Two decades behind the wheel has had its share of moments which were “real dandies.” She recalled one winter when a snowfall stranded children from regular school routes for days. During a torrential blizzard, one driver had to leave the bus and feel her way along a snow fence to a house in order to get the children into safe shelter. “There’s been many a time when I’ve left my last youngster off and said thank you God for getting me home,” recalled Mrs. Beattie….

Having considered a teaching career at a younger age, the dream was somewhat fulfilled after being acclaimed as a school board trustee for the area from 1983 to 1985. This came after serving on the Lambton College Board of Governors from 1976 to 1979. She was viewed as a natural choice for school board trustee position during a time when the East Lambton Secondary School was threatened with closure. A major effort by the town reversed the trend occurring in smaller towns.

Mrs. Beattie’s memories have been assisted over the years by keeping a diary for the past quarter-century, a habit her father got her started on.

Another fulfilling aspect of her life has been helping her husband with Watford Rotary Club work. Their involvement included taking part in an international student exchange program. One student from Brazil returned for a second visit since the initial exchange and brought her mother and sister. Male students from Holland and Germany continue to write, which Mrs. Beattie said shows the friendship the Rotary Club has created. “It was one of the most pleasant experiences of my life.”

Reminiscing with Clayton Cable

(written by Maxine Miner pre-2006, after telephone conversations with Clayton)

Bear Creek as it enters the Conservation Area: This creek has played an important role in the development of Twp., first with saw and gristmills, later for recreational purposes. Courtesy P Janes.

[Clayton Cable was born in 1925 and left the Birnam area in 1948. Maxine Miner was a neighbour of his. Maxine has lived in Warwick Twp. all her life.]

Maxine: …. That old Bear Creek sure wandered all around through our family’s farms, didn’t it? So much creek flats and willows…. Our bridge would always wash out every year, when the water came in a roar through there. We had a deep hole in the creek too. We never skated on it, because it might not be frozen hard. Remember how the ice used to let off booms? I was always scared of those spring floods…. Well, there was that other small spring creek out behind our house that crossed the road…. Indians used to come to it and catch Bull Frogs, great big one they cut off the legs, and take them to sell at the Hotels in Sarnia.

Clayton: Do you remember that place they used to store ice over behind Ernie Campbell’s old house? It was dug down into the ground, there was steps down into it. The men used to cut blocks of ice back in the creek and pile them in there. They’d get a load of sawdust, probably at the Saw Mill, to cover it over and it would keep all summer for keeping things cold.

Maxine: … Joyce Emmons said they used to put the cream and butter down in there where it was always cool. That was before any thought of hydro and refrigeration.

Clayton: Do you remember that bad winter about 1944? That was before Warwick bought the first road grader. That was always a bad spot a bit west of your place and Luckham’s bush. Blowed in to the top of the fence….

There were several funerals that winter. Had to get through to the cemetery up the Fourth Line. Didn’t keep them over back then. The men would shovel out the drifts all up through there. Mail didn’t get through either for some days. Then some one would get out to town with a horse and cutter if they still had one, and bring out some groceries and the mail from town. Man, that was like getting out of jail almost, wasn’t it?

Memories of St. Peter Canisius School

(written by Sister Rita Dietrich; submitted by Julia Geerts, 2006)

[Students in the Watford area would remember Sister Rita as Mother St. Louis. She was 37 when she was asked to start St. Peter Canisius School in 1958. She lived in London in St. Angela’s College until the convent in Strathroy was ready, then she commuted from there. She already had over 10 years teaching experience. Following are some of Sister Rita’s memories.]

“Bishop Cody was the Bishop of London Diocese. He considered the Watford area as the most needy place in his diocese, because so many immigrants had come to make Canada their home. He wanted a Catholic School, so that the children’s faith would be preserved. He made the request for two Ursuline nuns, so Sister St. Louis and Sister Mary Anselm were commissioned to go.

“Father Oosteveen, the pastor at Watford, made several trips to Brescia College that summer to see me, to inform me of the situation and to order supplies, etc. The big issue was that the school would not be ready for the beginning of the school year. He told me that classes would be held in the Lyceum Hall.

“I can’t recall the first day of school but I do remember the children going up those long creaky stairs. We had no desks but piled benches so as to divide the area into two classrooms. We used card tables for desks. This did not make the students happy as they couldn’t do their best work. Every Friday night we had to put everything in boxes so that the town’s weekend activities could take place. This was probably where the “open concept” for schools originated!!!

“I recall how well-behaved the children were. Their knowledge of English was limited because they probably did not hear it spoken at home. But they were ambitious. Their public school friends did not appreciate them leaving the public schools, so they used to tease our children by saying such things as “O, your teachers are nothing but witches and penguins.” They were totally ignorant of the 'habits' that sisters wore at that time. At the same time our children were very happy to be in a Catholic environment. They were offended by their friends’ comments.

“The first year we experienced very cold, icy weather which made the travelling from London exceedingly difficult. Furthermore, the car we were driving was fond of having flat tires. Thanks to the truck drivers we were cared for. But, due to weather conditions we were, at times, late. However, we had put assignments on the board the day before and when we arrived they were mostly completed. Father Oosteveen took care of Sr. Mary Anselm’s class and Martina Donkers, a model student, took care of the senior class.

“We were living at St. Angela’s College in London during our first five months. Two sisters were dropped off in Strathroy each day to teach at Our Lady Immaculate School, which was started about five years previous to St. Peter Canisius. Then Sr. Mary Anselm and I went on to Watford. It was a happy day when the convent in Strathroy was ready for occupancy. We moved in on the Feast of St. Blaise, February 2. We always remarked that we 'blazed the trail' on that day.

“Father Oosteveen was well aware of the difficulties of that first year. He would, time and again, encourage us by saying, “Never mind, Sisters, the future is bright”. He visited the classrooms faithfully each week and he would always begin by having the children cross their arms and saying, “My children, the Kingdom of God is within.” What wisdom! It is a practice that I continued with the children the rest of my teaching days.

“We had no equipment, only a rough area to play in, so it was difficult. Now, this was not a problem during our first two months, as we spent the time going out to three or four homes to use their washroom. We were not allowed to use the facilities in Lyceum Hall. We would assign the younger children to monitors to lead the way.

“After some weeks had gone by a crate arrived containing the statue of St. Peter Canisius. We assembled in the hall as we watched Father open the crate. Joanne, a Grade one student said in a loud voice “Oh, but he is brown.” Statues were supposed to be coloured. She probably voiced what most of us were thinking.

“We were anticipating having no more than 35-40 students but when day one came we had closer to 100. That first year I had five children from the same family.

“One Sunday afternoon Bishop Cody came to bless the school. It should have been a pleasant celebration but the town officials appeared quite glum. We (Catholics) were really not welcome in town, much less a Catholic school. That is the way it was then. "Thank God, things have changed. The senior classrooms, which our talented children had decorated, were the place the ceremony took place. A number of Ursulines from London were there to support us. My regret is that we did not own a camera at that time so no pictures are available. Anyway, we were too busy just surviving. Records were the farthest thing from our minds.”

Memories by Janet Campbell Fowler

(submitted by Janet Fowler)

My parents were John and Lottie Campbell. We lived on the Fourth Line North, Warwick Township. Our farm was between 12 and 9 Sideroads. I went to SS #19 on the corner of 6 Sideroad and the 4th Line.

About 1860 my Grandfather Campbell came to Warwick Twp. He married Margaret Brandon in 1863. Our family history tells us that Grandfather taught school in the first formed School section in the township, SS#1. The schoolhouse was situated on the corner of 6 Sideroad and the Blind [Chalk] Line….

The James Brandon family lived on the west side of our farm. James Brandon and my father were first cousins. Their daughter, Marion (Brandon) Johnson was my very best friend. She married Douglas Johnson and still resides in Bosanquet Twp….

My parents raised Mr. Howard Huctwith. His father had died when the family was all very young. To me, Howard was not just a cousin; he was my brother. He was well-known for his interest in farming. His egg-grading business in Forest began in the 1930s. He and his employees sent many eggs to Great Britain in WW II. I am sure the Armed Forces and citizens of Great Britain remember the eggs that had a stamp on the eggs — C. This was C for Canada!

The eggs were first brought to Forest. There were several “benches” (2 ladies re-graded the eggs and one person stamped the eggs with C for Canada.) I am not sure, but we did hear that the ship our eggs were on was sunk by “Jerry”.

The “Egg Inspector” was a very busy person. I believe he inspected other Egg Grading Stations in this part of Lambton and Ontario.

As a young child, I can remember when my father was a member of Warwick Council. I believe he did get to be deputy reeve, perhaps in 1933 or 1934. I believe he tried for Reeve but his friend Mr. Muma won. That is life!! It was during the “dirty thirties” and he felt then that we had enough to do trying to keep the farm going. We had built a new hen house in 1929. It kept us “‘poor” until the war started in 1939!

One time (late 1920s) the members of all the Township Council went to Detroit on a boat down the St. Clair River. We went to “Belle Isle”. There was a museum and of course the Ferris Wheel and other rides!

We boarded the ship in Sarnia off the “Ferry Dock Hill”. The ship would pick up passengers from both Canadian and American towns along the way. At each stop, little boys would dive for pennies. My mother was horrified but these kids were used to it though. It was still dark in the morning when we left our farm, the cars then only went about 25 miles an hour! It was such an exciting time! I can still remember the museum. It must have been quite a modern idea to display living sharks and all kinds of fish in salt water. They were all behind heavy glass. It was dark when we returned to Sarnia. (Since I was so young, I can’t remember the ride home!)

Grandad planted 4 ½ acres of fruit orchard. We always had fruit to can for the winter. I’ll never forget the rhubarb plants. The area was about 50 feet long! Plenty to give away as well. We ate well during “the dirty thirties” thanks to Grandfather’s wonderful planning. Before the Depression, my father used to send barrels of graded apples to Great Britain. That stopped after October, 1929. Then we sent the apples to the Vinegar Works in Forest. I think he got 50 cents for a bushel! He even took bushels to the CNR (Forest). Alberta was starving. I hope they got them. Ontario sent food out to the Prairies. They were blown away in the dust storms.

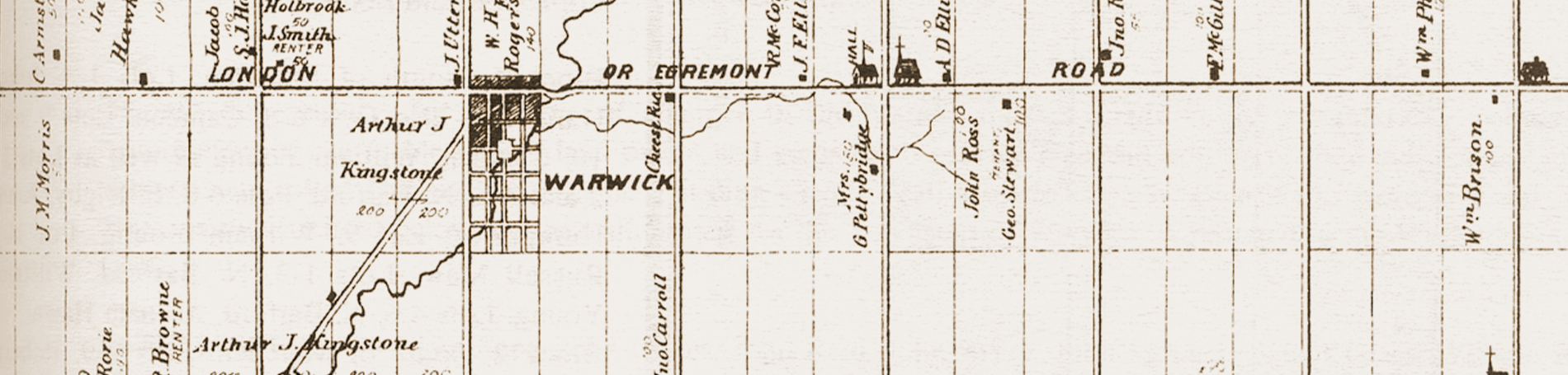

Growing Up On The Egremont

(by Margaret McRorie Frayne, from Eight Daughters & One Son, F. Main, 2001)

I have many positive memories of growing up in the McRorie clan on the home farm on the Egremont Road near Warwick Village in the 40s, 50s and 60s. Life for our family of six children centred on the farm, the school and the church…. On the farm we saw our Dad (Bill McRorie) share farming chores with relatives up and down the Egremont Road. Stacey Ferguson would help Dad with baling hay. Clarence Wilkinson owned the combine with Dad. Uncle Jack (Main) was there for silo filling as well as a table full of other men…

I spent many hours visiting my Granny (Agnes McRorie) who lived in the other half of our farmhouse. She read Uncle Tom’s Cabin and “Paradise Lost” to me…. She tried to teach us knitting and crocheting, but the big attraction was her cookie jar of gingerbread cookies….

We spent hours with cousins making forts in the barns and dressing kittens in doll clothes. I remember wild rides behind the tractor with brother Allen pulling us on a toboggan…. I still miss the close family feeling of growing up among relatives who were friends on the Egremont Road.

Who's at the Door?

(compiled by Mary Janes)

A memory discussed by several Warwick Twp. History Committee members was that of salesmen and transients coming to their homes. There were four kinds generally — hoboes, small wares salesmen, salesmen representing companies and gypsies.

In the 1930s Bill Bryson lived on Hwy 7, which was well-travelled. Hoboes and pedlars often came to the Bryson home asking for a meal. His mother never turned anyone away, even if she had concerns about them. He remembered one transient in particular. The Brysons had regular kitchen chairs plus a stuffed rocking chair in the kitchen. The hobo sat in the rocking chair to have his lunch. After lunch he said thank you and left. Mrs. Bryson immediately asked her son to help her take the chair outside so she could burn it. Bill was puzzled but his mother believed that the hobo was covered with lice.

Mr. and Mrs. William Loftus McLean of Huron St., Watford also talked about hoboes in an interview with their granddaughter Brenda in 1978. They said, “Oh yes, there used to be different tramps around, you know, and come in and ask for a bite to eat, you know. Used to see them in the Depression years, 8 or 10 of them riding the cars on the railroad; [you] see the railroad went through my farm.”

Florence Kenolty wrote of family members speaking about Billy Lagallee (spelling uncertain), the little fellow who walked all the way from Forest to their home on East St. in Sarnia carrying a suitcase. It was said that he slept in the fields on his trips. He sold shoe laces. Her mother would always buy some and give him a meal. He often sat on their porch lamenting and crying because people teased him and wouldn’t buy his shoe laces. Known also for his bad temper, Lagallee had applied for a job in the Basket Factory in Forest in the late 1920s but they would not hire him. People believed he got even by slashing the laundry on the clotheslines of anyone who worked at the factory.

Terry Laird of Thedford also remembered Billy Lagallee. In his memories Billy was a strange looking man with a beard who wandered about selling pencils, needles and thread. Terry thought people were afraid of him and chased him away.

Jimmy Smith, Warwick Village: Jimmy was well known in the Warwick area. In a book given to the Warwick Twp. History Committee he signed his name as “Jimmy Smith, Jack Knife Trader”. Courtesy W Dunlop.

Jimmy Smith is another pedlar remembered by people who lived in and close to Warwick Village. He lived in a shack in the village on Lot 4, east of George St. Jimmy was often teased by school children. The History Committee has been given a small Bible with his signature in it, and under the signature “jack-knife trader.”

In summer, natives would walk the roads selling baskets. Transients like fish mongers have been mentioned. Other frequent visitors were the Fuller Brush man, the Raleigh man and the Watkins man. Russell Duncan’s mother mentioned in a August, 1919 diary entry that “Russel [sic] got a new coat from a peddler $27. Dan got a ? sweter [sic] $9. and a pair of overalls and two pair for Bert.” Who or what kind of pedlar this was is not clear.

Lew McGregor remembered that after hydro came to the neighbourhood the vacuum cleaner salesman also came to the door. He also remembered a man who drove an old car, possibly a 1926 Chevrolet. He would drive through the neighbourhood, stopping at the road and checking for knives, scissors and other items to sharpen. He had a grinder mounted on the back bumper and would jack up the one wheel on which he had a pulley mounted to drive the grinder by belt. He had a stove in the car with a chimney out through the roof. This transient lived in this car and traveled across Canada plying his trade.

Another group of transients remembered by the Warwick Twp. History Committee was gypsies. Traditionally, gypsies are a wandering people whose origins are in Asia. Over the years they moved across to Europe and eventually to the rest of the world. They were noted for their dark skin and free life style. William Frederick Johnson in his More of Arkona Through the Years, 1988 noted that local octogenarians remembered a family of gypsies who spent ten to fourteen days camped at the intersection of Tamarack Line and Quaker Rd. in Warwick Twp. They came each year travelling in a covered wagon drawn by two horses. The living quarters in the caravan were supplemented by a tent. From there, the parents and older children visited the neighbouring farm homes, selling their wares, begging and horse trading. The family of gypsies remembered by Will Johnson was known as the Watsons.

Other local residents remember gypsies as well. Janet Firman remembers that, when she was a child with her family on the Egremont Rd. in the 1930s, they also had gypsies come by. The women would come to the front door and walk right in. The men would go to the back door of the house. The women always had fancy work such as lace doilies to sell. Money was not plentiful, so her mother would buy some doilies, but pay for them with preserves.

The August 9, 1967 issue of the Forest Standard, in its Looking Back! column noted that, in 1937, it was reported that Robert Campbell was robbed of $25 by two gypsy women while he was working in a field on his farm. They had a conversation with him, but after they left he noticed the money was missing from his pocket.

Cliff Lucas, in some notes of the Watford Historical Society collection, recalled that gypsies came every year from Grand Bend to 21 Sideroad. They wanted to trade horses. One particular gypsy by the name of Watson asked if he could have some hay to feed his horses, just enough that he could put it in a rope to carry it on his back. By the time he lay the rope on the ground, filled it with hay, and wound it around, he had so much hay he had to drag it along.

Burt Duncan, in 1983 notes from the Watford Historical Society collection said the gypsies parked on 15 Sideroad. They liked a sideroad where there was a creek and no railroad so their horses could roam. He said there would be three sets of gypsies a year. He also said the gypsies would collect and dry nettles, and then powder them. They would mix a teaspoon of nettle powder with three cups of oats to feed their horses. This would cure the horses of prickly heaves for a few weeks and hide their sickness until they could sell the horses. Burt thought the gypsies stopped coming around by World War II, when they either had to have work or be conscripted.

Russell Duncan, who lived on Confederation Line west of Watford, kept a diary from 1914 to 1920. Although the diary gives few details, it gives a picture of daily life on the farm. He does not indicate any interaction with gypsies, but they are mentioned regularly, so they must have been a significant part of life. The following are some of his entries.

August 5, 1914: Big crowd of gypsies at corner.

June 14, 1915: The first bunch of campers came along today.

July 25, 1915: A gang of gypsies came back today.

August 2, 1915: A big bunch of gypsies came along today.

June 16, 1916: Another bunch of gypsies came along today camped in front of Mr. Cameron’s gate.

June 20, 1916: The gypsies left.

July 19, 1916: A quartet of male gypsies arrived yesterday.

August 14, 1916: A gang of gypsies here.

August 11, 1917: Another gang of gypsies came along today.

When Russell’s mother started keeping the diary after he went to war, the entries were not as common, but on August 11, 1920 she noted that “There is a lot of gypsies at the corner.”

Some, but not all, of the people at the door tried to earn a living by selling something. Generally they were polite. The salesmen, for example the Raleigh man, were of a different category but, as for the transients, no-one seemed to know where they came from or where they obtained their wares. Mostly they were around Warwick Twp. in the era between the two world wars, when food was more readily available in the country than in the city. Some were much like the homeless people in many of our cities in 2008.

Farmerettes

(submitted by Alexia Clark Landon)

[Farmerettes were an integral part of rural Ontario during the war years when the men were off to war. Although the Committee did not receive any experiences of farmerettes working in the Warwick area, this story was submitted of the experiences of a Warwick Twp. resident working elsewhere in the province, and gives an idea of who farmerettes were and what they did.]

In the early spring of 1945, I went, as a farmerette, from my home in Watford, Ont. to Vineland, Ontario in the Niagara Peninsula. A High School teacher, Adam Graham, had family connections to the Government Experimental Farm there. He recommended that I apply. I went by train, early in March, having achieved satisfactory marks in the school examinations to merit being excused from completing the next, final semester. This was important as I intended to go on to the University of Western Ontario in the fall.

The facility consisted of a large two-storey warehouse converted to dining hall, kitchens and several small administration offices on the main floor and a large dormitory above, with single beds along the walls and double bunks down the centre of the room. There were also one or two bunk houses across the lane alongside the main dormitory. There were lavatories and shower rooms. Several of the showers had privacy partitions, but mainly the shower heads were above open areas with a central drain. On a hot day after working in the fields, these open showers were so crowded that one did not know if it was one’s own arm or someone else’s that one was scrubbing. At one time there were a few French-speaking girls from Northern Ontario, who were not comfortable speaking English, and they showered in their bathing suits, in the other shower area where the stalls were more enclosed….

As I recall, at peak demand, there may have been over 100 girls going out in the early mornings to work on neighbouring farms. We would rise early, have breakfast, make our lunches from a bountiful supply of sandwich makings, fruit and sweets (cookies, brownies etc.) These would all be prepared by the kitchen staff, who were, of course, up even earlier than we! I think most of the kitchen girls were farmerettes as well, with hired overseers, but I am not certain of this.

The transportation would arrive and we would all go off to our assigned farm. Transportation was by private vehicle, sometimes the back of a truck. We cut fields of asparagus. The farmer I worked for had acres of the stuff and we cut it twice a day during the warm damp prime growing period, bending over, wielding a sharp curved knife to reach just below the soil and stacking the resulting asparagus spears in 6 qt. baskets which were trimmed to 5 or 6 inch lengths and packed again for delivery to the canning factory. We weeded and thinned miles and miles of baby vegetables — beets, carrots etc., just emerging in the newly seeded rows. We thinned newly developing peaches and pears so the remaining fruit would be prime size and reaching the sun for prime colour. We picked bushels of cherries — sour red, sweet red, black and a few of the wonderful white Oxheart…. Every piece of fruit was money, and not one was to be left on the tree!

I recall one day we were picking strawberries. It was a hot day with bright sunshine. Someone wondered what that funny smell was. We decided it was the skin on our thighs cooking, as we had to wear overalls, but of course, rolled the legs up as far as we possibly could! …

On rainy days and on week-ends, when we were not working, the girls from the Vineland Camp would “hit the road” and hitchhike into St. Catherines. We were forbidden to go alone, so we traveled with a buddy…. However, there was a place called The Lighthouse just down the road where there was a juke box and dance floor and young people gathered there. It was a reasonable walk home if one was not one of the fortunates to get a ride with one of the local young men. How the local young women must have hated us.

A Chapter in Warwick Education

(submitted by Rev. Graham MacDonald)

I was appointed in September, 1958 as Public School Inspector to a new inspectorate called Lambton 3 and Middlesex 4, with an office in Watford. Because of the number of “baby boom” children, an additional inspectorate was needed to care for the increased pupil population. My new inspectorate extended from Grand Bend to Wardsville.

[My wife] Freda and I and our two children moved into our John Street house, newly constructed by Moffat and Powell, in 1958 and we were warmly welcomed by the people of Watford.

During early settler days, Warwick Township had been divided into rural school sections, each with its one roomed school and board of trustees. These schools, with faithful teachers, had served the residents well, but change was on the horizon. The Province was promoting the formation of township school areas, whereby most or all of the former township school sections came under one Board. The Province was also promoting the building of township central schools to enhance the education of pupils in changing times.

In the early 1950’s, Warwick Council amalgamated most of the school sections into Warwick Township School Area (TSA), which included a Board with five trustees [Chair Stacey Ferguson, Secretary-Treasurer Clarence Wilkinson, Arthur Muxlow, Keith Howden, Bruce Carruthers and Lloyd Quick]. This was a courageous move because at that time many people in Ontario favoured no change to their existing school boards. I believe two Warwick school sections preferred not to become part of the larger unit and the Council honoured their wishes.

Clarence Wilkinson was appointed secretary-treasurer of the new Board, a position he held for several years. He was a progressive thinker and an efficient secretary. The prime objective of the new Warwick Board was to investigate the construction of a central school. Accordingly, the trustees visited the very few existing central schools in operation, including East Williams Central, the first central school in Middlesex County. After serious consideration the Warwick Board said, “Let’s go for it!”….

Warwick Central School staff: Back: Marilyn Dewar, Hazel Brandon, Margaret Redmond, Graham MacDonald (inspector), Joan Woods, Dorothy Shea. Front: Colleen Wakefield, Frank Moffatt, William Stewart (principal), George O’Neil, Marilyn Dolbear. Courtesy WG MacDonald.

When I arrived on the scene in 1958, Warwick Central School was already in operation, newly constructed on Highway 22. It was a well planned structure of six classrooms. John Beaton was the principal and he had capably organized the transition from several one-roomed schools into one school building. The hard working teachers were dedicated to providing relevant instruction for the pupils.

The trustees were determined to provide a good learning environment for the students and they succeeded well. They were a co-operative and forward thinking group of men and some of them were Donald Ross, Ivan Parker and Alan Roder. In those days, women did not serve on school boards, but that came later and women proved to be good trustees….

Warwick Central enrolment continued to increase and soon it was evident that an addition was needed on the school. This involved many planning meetings and consultations but eventually additional classrooms, and, I believe, a kindergarten and gymtorium were added to the building. I remember standing with Secretary Clarence Wilkinson outside the school discussing the plans for the addition. From where we stood we could hear over the school’s PA system a report of the progress of astronaut Alan Shepard, the first American in space who at that moment was circling above the earth in his space vehicle. Truly an historic moment….

Kindergartens were new for rural pupils and a programme was started at Warwick for the children to attend full days on alternate days. The arrangement worked well and provided another educational advantage for country children.

Some years later, before 1967, the parents in the two remaining school sections began to hear favourable reports of improved educational opportunities at Warwick Central and so they asked the Council to include them in the TSA. The Council agreed and so all children in the Township had equal educational instruction.

Following my visits to a school, I would meet with the staff, mainly to encourage and compliment the teachers on their endeavours. Later I would meet with the Board to discuss instruction and leadership at the school, and to suggest needed repairs or additional educational programs. Always the Board was most co-operative in following suggestions for improvement.

The enrolment continued to climb and it wasn’t long before another addition was needed on the school. So, more meetings, more plans. When that addition was completed, Warwick Central was a fine looking building and the efficient teaching staff provided a first rate educational programme for the students. I remember, too, the good custodial work done by the caretakers.

Board and staff were willing to provide additional learning programmes for the pupils. An Opportunity Class was established for pupils who required special learning assistance. George O’Neil taught this low enrolment class and did a fine job of organizing a sound programme. As I recall, this was the first special education classroom in a rural school in Lambton. Later the Board agreed to engage a remedial teacher to assist pupils who needed some catch up assistance in mathematics and reading. Frances O’Neil filled this position very well. She and George were kind and understanding teachers and gave much needed assistance to many pupils.

The Board set up an efficient busing operation for the students. Early on, with a view to providing economical bus transportation, the Board decided to buy and operate their own buses. The system worked quite well at an economical cost. Some other Boards in the area followed their example.

During the early sixties, a new method of teaching primary language and reading, known as Language Arts was introduced in Ontario schools. Warwick teachers adapted suitably to this method of instruction.

With changes coming quickly on the educational scene, almost anything we did was innovative and exciting. Warwick principals and teachers gave leadership in many of our endeavours. We set up an Inspectorate Principals’ Association. We organized an annual Inspectorate Field Day. I remember John Beaton standing on a flat bed truck when he opened the first Meet with the stirring words, “Let the games begin!” We held annual science and history fairs. We established the first teachers’ summer course held in a rural area. Teacher Federations were becoming well organized and promoted the interests of teachers….

It was a busy life. Over the years, I assisted all the Boards in my inspectorate with construction of new schools or additions to schools. I attended meetings most evenings of the week. But those were exciting and rewarding times! When I came to Watford, there were 63 school boards. When I left in 1969, the number was reduced to 10 boards.

Each year the Warwick Board asked me to calculate their expected legislative grants. They needed the figures so they could prepare their budget and the Council could set the educational tax for the ratepayers. It was important my calculations be accurate. Some portions of the Regulations were difficult to interpret, but fortunately (or maybe just by luck!) my figures were reasonably correct, and I breathed a sigh of relief when the final grant was received in the fall.

It wasn’t all work and no play and we had many enjoyable events. Each Christmas season Warwick Board held a social evening for all employees at the Township Hall. Each teacher received a Christmas present. The evening was spent playing cards and I remember, for two years straight, I received the booby prize. Obviously I never did well at cards!

Warwick and Watford schools held annual spelling and geography contests for senior students. It was the Inspector’s task to provide the geography questions. Many students took part in these contests which were stimulating events. I remember one year one of the questions was, “What is the most southerly point of Canada?” My source said the answer was Point Pelee. However, a bright lad from one of the schools pointed out to me that his encyclopaedia said the answer was Middle Island in Lake Erie. He was right, and thereafter I checked my answers even more carefully!

Another area of interest was the annual public speaking contest sponsored by the Trustees and Ratepayers Association. Several Warwick pupils took part in the contest each year and won awards at the different levels.

Warwick Central graduates attended East Lambton Secondary School, where Frank Michie was principal for several years [also at North Lambton Secondary School in Forest]. Many Warwick students went on to successful careers and to hold responsible positions in their adult lives.

In January of 1969, the Ontario Government formed County School Boards, whose officials would hire their own superintendents. I was hired by Middlesex County Board of Education, and so began a new and fulfilling chapter in my life. [Adelaide Township Central School — W.G. MacDonald School on Egremont Road was named in Graham MacDonald’s honour.]…

The story of the proud Warwick Central School is now history, ending a productive and progressive era. The building has been sold and is used for other purposes [a truck drivers’ school]. Watford and Warwick are now one municipality. Warwick Township is part of a very large District School Board…. Change, it seems, is ever with us…

Freda and I enjoyed our years in Watford and Warwick. Our adult children still remember the area as “home” for their growing up years. We were privileged to live and work with the many good people we met during our Watford sojourn.

Those were good years!

The Life Of Agnes Campbell McCordic

(by Francis McCordic)

[Agnes Campbell was born in 1880. She married Francis McCordic in 1903.]

Agnes’ Uncle William, who lived with the rest of the family about a mile west of Watford, was very fond of thimbleberries. In those days these berries grew wild on the Stoney Point Reservation abundantly. In early August one year William drove to Aggie’s home and took her along with him to this berry patch. They picked a good quantity of fruit but it was hot work and they became very thirsty. They called at an Indian home and asked for a drink of water…

McCordic Clock: This clock was bought in Scotland by William and Jean Smith after their marriage in about 1808. It came with them to New York about 1833. In 1840, the Smiths moved to Twp. The clock was bequeathed by William Smith to his granddaughter, Jean Laidlaw Kingston (Mrs. Jean Campbell) and remained on the Kingston homestead, Lot 15, Con. 4 SER until the death of John Kingston in 1927. It then moved to the home of her daughter, Mrs. Frank McCordic of Toronto. On the death of Mr. and Mrs. McCordic, the clock was given to Robert McCordic in Ridgetown, Ontario. In 1970, Robert moved to Bosanquet Township and the clock came back to Lambton County. The clock still keeps good time and rings out the hours faithfully. SOURCE: Robert McCordic

McCordic clock. Courtesy R McCordic.

Many a journey was taken on foot, Agnes told me that she and Stella Knapp, when they were little girls, walked to Forest, which was four miles from her father’s home. From Forest they walked to Dolly McKay’s home on the Warwick-Bosanquet townline, about two miles from Forest. A rain storm came on while they were there and they stayed with Dolly all night. The next day they walked to Six Sideroad, crossed over to 6th Concession of Warwick and then home, a journey of about four miles for Agnes. There were no telephones in the farm houses in those days and no way of informing their parents of their safety in Dolly’s home. Such was life at the time, and father and mother had to have faith that all was well.

When she was sent to Forest High School, farm produce brought very little money on the market and Agnes lived, for the five school days of the week, with another girl in a room or two, rented from a householder in the town. The girls set up a wood-burning stove and prepared their meals with food brought from home on Monday morning. Agnes lived for the school days of each week in this fashion for over two years.

To get up in the morning, light a fire to warm the room, cook the meal and wash the dishes, before leaving for school each day, and repeat the process at noon and then do this work again at supper time was not luxurious living. In fact it was a real hardship, but few pupils complained. However, digestive powers often suffered.

When we were children old dobbin [horse] was the motive power to take us from place to place, when the distance was too great to go on foot. But there was a companionship when riding along the road in the family buggy with a friend at one’s side that is difficult to realize in the fast moving automobile. I think this delight was greater when two people with a robe below them and one above, with fur gauntlets, woollen scarves and warm caps, in a high-backed cutter, rode across the snow, the motion of the horse sending tingling of bells into the frosty air on a starlit night. When the moon rode high in the sky it was ecstasy indeed. No modern means of conveyance, methinks, can bring the joy of cutter and sleigh riding of those early days. It is a fond memory that comes to us to-day. Oh, of course, sometimes the cutter upset in the deep snow but that was part of the fun, for very seldom did such mishaps do much harm.

The jolly sleighing parties were neighbourly affairs in those early days. A group of young folk secured an ordinary farm sleigh, put some clean straw in the bottom of it, laid a robe over this and with plenty of robes to put over them, jumped into the sleigh drawn by a team of horses and to the sound of sleigh bells away they went over the glistening snow. I know of no outing of the present time that gives young people such wholesome fun and delight as those sleigh rides in the bracing air. I feel some of the neighbourliness has gone as well.

While speaking of neighbourhoods I wish to refer to other gatherings. There was the paring bee. Before the days of cold storage the apples from the farm orchard were dried or evaporated in the home. The neighbours came to the homes, one after another, in the winter evenings to pare [peel] apples, quarter them and string them on common white cord to be hung up to dry. At these bees there was much jolly chatting, teasing and friendly jesting. After the paring was finished there was singing and dancing, after which lunch was served.

Besides the apple-paring bees, there were husking bees followed by barn dances, and sewing bees when the ladies sewed patches together for quilts, or sewed strips of cloth together for rag carpets, during the afternoons. After the quilting and rag bees the men and lads came for an evening get-together. The power of these social events to hold a neighbourhood to a friendly mood cannot be over estimated. We seem to have very little to-day to take the place of the bees of early days to keep us acquainted with the real spirit of each other.

A few years before the turn of the century a friend of mine invited me to spend the night at his home. While there I was introduced to the telephone. A line had been built connecting the farm homes with the village doctor. It was not necessary any more for a farmer or his wife to call on the neighbour to chat or exchange ideas. This might be done over the telephone. It was true that all farm houses had not telephones for many years but a beginning had been made and changes were setting in that have made vast changes in rural living.

It was in 1888 or about that time that I saw the first bicycle or rather saw one for the first time. It had a large front wheel with pedals attached to the axle, and a small rear wheel. To mount this vehicle was an art mastered only after many trials. To remain on it meant continuous pedalling with a keen eye on the road ahead. It was not difficult for a rider to be thrown forward to the ground if the large wheel hit a small stone or a slight hump in the roadway. In a few years the safety bicycle, as we called it, appeared on our highways and the bicycle age was upon us. Dobbin was being displaced, or at least the first stages [of that change] had begun.

Before 1900 I had ridden many miles on a bicycle, going as far as eighty-five miles in one day. Scarcely a week went by that I did not travel one hundred miles in going back and forth to school or to town and taking hikes with friends. My neighbourhood had grown in area, and that intimacy with the folk in the homes nearby, gradually was growing less. Agnes never rode a bicycle although its use might have saved her much walking,

We were living in Point Edward when we first saw a horseless carriage and that was in 1904. It was propelled by a two-cylindered motor and its slow chug, chug could be heard for a long distance. I fancy it travelled little more than ten or fifteen miles per hour. Soon came cars with four cylinders that ran hair-raising speeds of twenty-five or thirty miles per hour. These cars had greater refinement, and it was a common thing then to lengthen out trips to forty, fifty or even more miles. The old intimate neighbourhood was further losing its ties. The one thing that retarded this was the fact that not many people could afford to buy such a means of conveyance for some years to come. How the horses shied when passing one of these horseless demons in those early days.

Growing Up in Warwick in the 1930s and 1940s

(submitted by Lewis McGregor)

Farm Life

Farm life hadn’t changed that much since our ancestors settled in Warwick in 1832, except for the coming of the automobile and the tractor, which were of little use when winters were bad. The children were all expected to help with the daily chores. Starting at a very early age, the boys would bring in the firewood, get the milk cows from the field and do other little errands. The girls would usually be busy helping with the household duties, learning to cook and sew, although some preferred the outdoor life and could be found helping in the barn and fields.

By age seven or eight, a boy could be found splitting and piling wood, attending to livestock or working in the fields, there was always something that needed doing. There were gardens to hoe, apples to pick, hay to mow, grain to cut and stook, water to carry from the well, and in winter snow to clear. Farming was done by manual labour in these times. In most areas hydro had not been installed. Lamps and lanterns were the source of light and much care had to be taken, so you didn’t burn the barn down. Hay, straw and other livestock feed was brought to the stable area during daylight hours, so you weren’t working in the dark.

Fire was a great concern. With no fire fighting equipment, a serious fire could wipe out a homestead. When this did happen the neighbours all got together to help. If you were lucky enough to save your livestock, they would be driven to a neighbouring farm and cared for until a new barn could be erected. If a house was lost, the people stayed with neighbours or other family nearby. A farm community was one large family caring for one another.

The land was worked in the spring and planted. The wheat had been planted in the previous fall. When the grain had matured, it would be cut with the grain binder, pulled by a team of horses, as there were few tractors on the farm in those days. While the father operated the binder the children and sometimes the mother would be busy stooking the grain, so it would dry for threshing.

There were only a few threshing machines in the area. They passed through the neighbourhood, from farm to farm. Each area had its own work section, consisting of the farmers in a two mile stretch, which consisted of about eighteen farms. These groups worked to help each other. They were notified of need for help by a long ring on the party telephone. One long ring and everyone picked up the phone to find what was needed. By age twelve many farm boys went to the threshing, as the man from their family farm.

Threshing was hard work. The grain had to be loaded on wagons, then drawn to the threshing machine and fed through. Most times straw would be blown into a stack for bedding and feed for winter. Sometimes it was blown into a mow in the barn. One man would build the stack. This was a dirty job in the hot weather and the straw coming from the blower was dusty.

Threshing time meant the neighbours getting together and helping each other. The women were busy for days before threshing day, baking and getting ready to feed the crew, at least two meals on each threshing day. This was the best part: a good meal and lots of stories and after a short rest it was back to the job.

The man who did the threshing in our neighbourhood had an old model A coupe. When it came time to move to the next farm, the teenage boys would scramble to get to drive this old car, which, I might add, had no brakes. We were instructed to gear it down and then run into a tree to get it stopped. Some times we got a little reckless and did some minor damage. Then we got a talking to and were threatened that we couldn’t drive again, but by the time it was ready to move again, it seems he had forgotten about this and we would be back behind the wheel.

Silo filling and buzz bees would bring the same groups together. The wood was often cut a year ahead, in buzz poles and then cut to stove length in the fall for next season’s fuel. The wood had to be piled in the yard or in a woodshed. This was usually done by the kids and then brought into the house each day, for heat and cooking.

The winter meant a barn full of livestock that had to be cared for seven days a week. Morning chores started early and would include milking by hand, turning the cream separator by hand, busting the ice in the water tank, turning the cattle and horses out to get a drink, feeding the livestock, cleaning the stable and bedding the stalls. Much of this was done before breakfast. Then it was time for a hearty breakfast, which was as big a meal as any other for the day. After breakfast there would be things to repair, feed to grind and other things to get ready for evening chores.

Grain was hauled to the mill by wagon or sleigh. Some farms had an old truck or trailer, but when the roads got bad, it was back to the horses. This job was often done by a young boy, who was trusted to handle it. Whether by horses or with the truck, many of the farm boys learned to drive at a very young age. And the town police paid them little attention unless they caused trouble. Then you could be sure your parents would be notified and you would be disciplined….

Because the farmers heated with wood the only other expense they had was groceries and possibly, if someone became ill, a doctor bill. In those days ten dollars bought a lot, mainly flour and sugar. Potatoes and other vegetables would be grown in their garden. They might even have a cow for milk, chickens for eggs and food and [they would] raise a pig to butcher for winter. The women in these times prepared all their food; it didn’t come out of a can. Some had no car and rode a horse to work or walked. Many of those that lived in towns or villages kept a cow and chickens and even pigs for their own use, selling what they didn’t need. Town people also had gardens….

Water for the livestock was pumped by windmill or with a small opposed firing gasoline engine (a stationary engine, usually one cylinder, with a handle by which it could be carried). Since the washing machines were hand operated, wash day was a busy day. Washing machines were later driven by small gasoline engines. I remember starting these engines before going to school. The one on the pump was no problem, but the washing machine had a mind of its own. And, of course, the cloths were hung on the line to dry. In the winter they would freeze and then brought into the house to finish drying. Not many farm women worked out in those days. They had lots to keep them busy at home. Many of them even helped with the chores.

The Centre of the Community

Rural schools served as community centres. Card games and dances were held in rural schools. Most neighbours attended and lunch was always served. Each family brought sandwiches or dessert, and tea and coffee would be made on site. The whole family would attend; the kids that didn’t dance found games to play.

When a couple got married, a shower would be held in the school. The whole school section would attend and the couple would be presented with a gift. Cards and dancing rounded out the evening. After the couple were married and settled into their new home, whether it be with one of the parents or a place of their own, a group of the neighbours would get together to shivaree them with shotguns and a buzz saw on a steel shaft. This was struck with hammers to awaken the new couple. They would get up and welcome everyone in and usually make lunch. While this was going on, some of the group would sneak into their bedroom and short sheet the bed or remove the slats under the springs except the centre one, so the bed would tip, when they got in. This was all in good fun, just a way of welcoming them to neighbourhood.

Other Times

Saturday night most people went to town; the stores would be open 'til midnight or after. While the ladies shopped and visited, in winter the men would sit around an old stove and share stories and catch up on community happenings. Some would take in a movie or play pool, especially the kids, who got twenty-five cents to spend, twelve cents for the movie, ten cents for a sundae and three cents left for Sunday School.

The garages would be open with one mechanic on duty. When we left the movie and had our treat we would go to the garage to wait for dad. The radio was always on, tuned into the hockey game or a boxing match. When it neared midnight, the garage would be closed and we headed for the butcher shop to get a roast or the grocery store before they closed.

In summer, we would bike to town and visit the dump to find bicycle parts to repair our bicycles. Sometimes we were lucky enough to find a repairable one and we would drag it home to fix it up. When we had spare time, we rode our bikes to visit neighbours or just toured around.

In winter we would find a frozen creek or pond, clear the snow and have a skating party or play shinny or find a hill to sleigh ride. In winter when the roads would be impassable by car, someone would hitch up the horses and sleigh, usually on a Saturday evening, and head for town. Before leaving they would ring the phone to alert the neighbours and if they wished to join them they would be at the road and ready to go. If they needed groceries, they would call the order into the store and it would be picked up and delivered. A lot of fun was had on these sleigh rides. The horses would be put in one of the church sheds in town, and we would head downtown, to shop, play pool or take in a movie. You would get home from one of these trips at two or three on Sunday morning. After delivering the groceries to everyone, the team had to be unharnessed and fed before you could retire for the night.

If the snow piled up too high on the roads, the neighbours got together and shoveled through the big drifts. Sometimes fences would be opened up so you could go through the field around the drifts and back out on a lane or other opening in a fence. I remember a time or two that Oliver Tremain was hired to open the roads with a plow he had mounted on a truck. He would have to back up and make several attempts before getting through the bigger drifts. You could hear this rig coming for miles. If someone was seriously ill, when the roads were blocked, the doctor would be sent for with a horse and cutter. If someone died, they would be taken to town by horse and sleigh.

In the spring when the frost came out of the roads, many bad spots appeared that would make it difficult; they sometimes were filled with hay or detoured till they dried up. There was very little equipment in those days to keep the roads in repair and even less to clear the snow.

In early times community meant one big family looking out for and helping each other. Today it is a definition of a location.

North Watford (1917 to 1924)

(by Leslie M. McIntosh; submitted by Don Hollingsworth)

Lieutenant Colonel R.G. O. Kelly, M.D., Officer Commanding the 149th Battalion died suddenly in December, 1915. His military funeral was reported in the 17 December [issue] of the Watford Guide-Advocate. The parade started at the armory and, while standing in front of the fire hall watching it, I was told there was a jail cell in the back of the hall. During my public and high school years the only person who was put into it in 1920 was a young Danish violin teacher who came to give lessons once a week. He had “borrowed” something and hadn’t returned it. If the authorities could have found out who the persons were who had transported houses about 54 inches square and 7 feet high and placed them on Main Street at Erie and Ontario there may have been more in it.

In the early afternoon of Sunday, 10 November, 1918, the town bell started to ring. Word had been received that the armistice was to be signed at 11:00 a.m. the next day. There was no Sunday School that Sunday. Boys my age and older walked the streets banging metal pails making as much noise as we could. At school the next morning one chap said some ladies, friends of his mother, had come to their place after they heard the news and were crying because the war was over. That too took me some time to comprehend. The Reeve declared Monday afternoon a school holiday and that night a high column of discarded wood, held up by four telephone poles with the Kaiser hanging at its top, located about where the War Memorial is now and beside the bandstand where the Watford Silver Band gave concerts (the Post Office location), was set on fire and gave a great blaze.

To start to public school a child had to be six years old by the first day of September. One, whose birthday was 1 September, could have a sister or brother whose birthday was 31 August the next year. They would both start to school the same day. The eight years of school were divided into four Books. Junior and Senior Book 1 were the first two years (Grades I and 2 now) and Junior and Senior Book IV were the last two years. Pupils (Parents) had to obtain their own Ontario Public School Textbooks.

There was a Reader and Speller for each Book and as pupils went along they got Arithmetic, Composition and Grammar, Geography, British History texts in Junior IV and Canadian History in Senior IV. Here are prices of texts with dates of publication in brackets: Book I Reader (1909) 6¢, Book II Reader (1909) 9¢, Book IV Reader 16¢, Book IV Speller 1909) 15¢, Composition and Grammar (1920) 25¢, Geography (1910) 60¢, Canadian History (1941) 30¢….

Three events took place took place when I was at Public School.

1. One morning of a twelfth of July “King Billy” dressed in his regalia came riding on his white horse from the north on Main Street for the Orangemen’s Celebration.

2. A barn or stable on the north side on Simcoe Street about the third lot east of Warwick Street burned to the ground.

3. The top of the tower of the Presbyterian Church was struck by lightning and started to burn. It was put out by Mr. Robert Spalding, an electrician, who went up the inside with the water hose. (That had to be before the eleventh of September, 1920, because he died on that date.)….

The most colorful one-day celebration of those years was Soldiers’ Day, August 20, 1919, for the veterans of World War One. A bulletin in the Guide-Advocate has “Let every house and building in Watford be decorated.” A great many, if not all, were. A grand parade started from the armory area to Warwick Street, then to Simcoe [St.] to the Fair Grounds, led by a band and the veterans. There, there were speeches, athletic events, a baseball tournament, and a dance in the armory at night.

Gladys, Eric, and Gwendolyn Craig, of the Ben Craig family, who lived in the house south of ours, Eleanor and I entered a float in the parade and got third prize. We divided the $10 prize among the five of us. For $2 one could buy 20 pounds of peanuts, or 40 ice-cream cones, or 200 licorice whips….

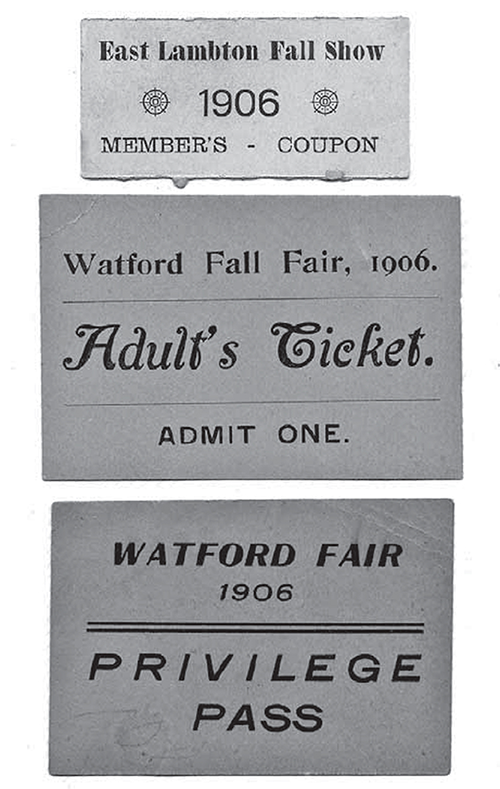

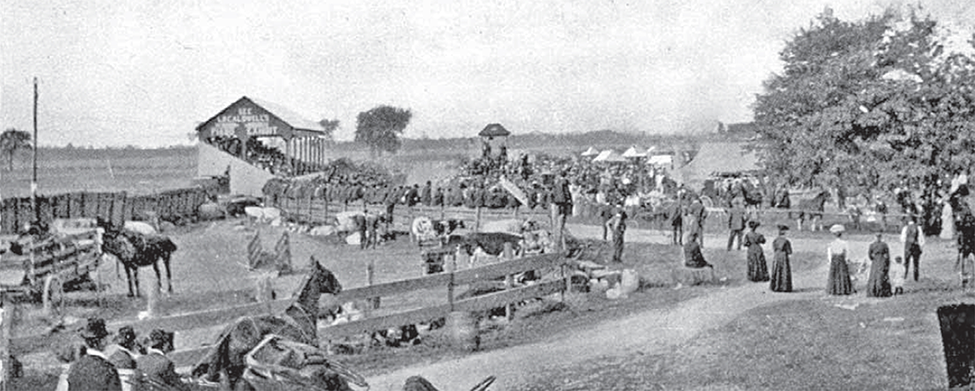

During the first day of the Watford Fair, there was much traffic on Simcoe Street as exhibits from the rural area were taken to the Fair Grounds. Vegetables, grain, fruit, flowers, baking, needle-work, knitting, were displayed on the second floor of the Crystal Palace. There too, if there was space, penmanship, essays, art work of the Public School Pupils were shown. If there was not room, a tent was used. The prizes for them were donated by the Women’s Institute. A midway with a merry-go-round, a Ferris wheel, tents for things to buy, (lots of dolls and carnival glass) and games-of chance. The most interesting thing to buy was the first year I attended — a glass blower in a tent among the trees was making animals and birds. In my Junior Book IV year, on my first try, I won a pocket-watch which lasted me five years. Cost was 10¢. That year there was a tent with machines from which, if a 1¢ piece was put in a slot and a handle was pulled, a trinket came out. One machine had pictures of baseball players.

Watford Fall Fair Tickets. Courtesy D Hollingsworth.

In the afternoon of the second day there was a baseball game, athletic events and entertainment on the platform beside the judges’ stand for the spectators in the grandstand on the other side of the racetrack. The three or four horse-races were the main attraction. A race was of three heats, a heat being twice around the half-mile track. To declare a winner, often the trotters and pacers had to go four or five heats….

The success of the Fair, which was at either the end of September or the first of October, depended on the weather. The Crystal Palace burned during the evening of 24 October, 1926. At the end of the decade, times seemed to become harder, softball replaced baseball because it was less costly. Because of the loss of the Palace and, as it had rained that Fair Day, enthusiasm for it diminished so it was decided to discontinue it.

The Village had a banner year in 1921. The water distribution system and the pavement on Main Street were completed and the skating-rink on Ontario Street was being built…. A hydrant was placed at the northwest corner of Main and Simcoe Streets. The residents of the four corners got the Village Council to put an open tap to which a garden hose could be attached on the hydrant. Each resident purchased a fifty-foot length of hose. The handle to turn the water on was left at our place. The summer was very hot and dry that year. I joined the four hoses together and sprinkled the roads the 200 feet. My father told me that Miss Hay, who lived on the northwest corner, was always grateful when I did it as it settled the dust and cleared the air. Miss Hay had hay-fever.

My uncle, George McIntosh, was a clerk in Peter Dodds’ Grocery Store early in the century. He told me about the dreadful condition of Main Street when the road thawed out in the spring. A lady brought a crock of butter, which she had just churned, to the store, to exchange it for groceries. The day was very warm and it had not yet solidified. As she was getting out of her buggy, the crock slipped from her hands, turned over, fell, and the butter mixed with the mud and water of the road.

East Lambton Fair, Watford Fair Grounds, 1906. Courtesy G Herbert family.

Watford Fair Grounds, May, 1923: The Crystal Palace, formerly ’s Drill Hall, is seen on the right. Courtesy L Koolen.

The crocks must have been supplied by the merchants so they would have quite a few. A customer would present her butter and get a crock for the next time. Elmer A. Brown, when I was working at his A. Brown and Company during my High School days, told me about his father receiving a lady’s butter. She asked him if he would do her a favour. He said he would if he could. She said that, when she was about to make the butter, there was a dead mouse in the cream so she did not relish putting it on her table and would he exchange it for her? He said he would be glad to do that. Each lady, with a butter spoon, put her special decoration on the top of her butter. Mr. Brown took it to the basement, where butter was stored because it was cool, smoothed the top, put another design on it, gave it to her and said he was sure she would relish this butter. She was happy.

In 1921 the Watford hockey team was good. On the 28th of February a play-off game with the Stratford Intermediate O.H.A. Hockey Club, including Howie Morenz, was in the Fowler rink. There was always good ice because there were small spaces between the vertical boards of the siding of the building. The score was 3-3. I had glimpses of the players through the spaces, as I didn’t have the $2.50 to get in.

As I recall the Fowler rink, it was about 50′ wide and 120′ long and was dubbed “The Pill Box”. The rink on the north side of Ontario Street between Main and Warwick streets was first used on 20th of January, 1922…. As the rink, having the shape of an arch and covered with sheets of corrugated galvanized iron, was being built, stores on Main Street were each given a keg of nails and a box of lead washers to be put on the nails to seal the nail holes in the roofing. Personnel of the stores, and customers, in their spare time did them. They were picked up by the carpenters when needed. My father was a clerk in The Farmers’ Store, which was on the east side of Main Street. In 1923 the building was purchased by Mr. W.H. Brown for his plumbing business. I was often in the store and many the nail I “washered”.

Carman Spalding was the friend I was most often with during Book IV and the first year at the High School. His father was the man who put out the fire at the top of the church steeple (tower). He [Carman] was left-handed so he played first base on the ball team. We played catch on the boulevard at the front of our place. When a car going north was beside him and at the same time a car was beside me going south, I would throw the ball to him and he would return it to be to me before his car got to me, we would have a double play. Sometimes we got triple plays.

There was a set of four single (for one hand) trapezes hanging from the roof of the drive shed of the Presbyterian Church. We and others spent time trying to swing from one trapeze to the others…

In September 1923, my last year at the Public School, a young man of about 22, became its Principal. A few weeks later, a man asked my father how the Principal was doing. He said “Fine! He gets out and plays with the kids.” After I became a teacher, I often recalled my father’s remark. As a teacher, he made his lessons interesting with his “wise saws and modern instances” such as: “They put buoys in water to mark channels instead of girls because a girl would float away with the first swell [great looking guy] that came along.” His method of teaching history, for example, was to write his notes on the blackboard, tell us to copy them, read the text, learn the notes, and then he would sit down and read the London daily paper. It worked, as his record of promotion was good….

The High School curriculum was divided into three Schools — Lower School (the first two years, called Forms), Middle School (Forms III and IV) and Upper School (Form V). At the completion of Middle School, a student was given a Certificate which allowed him or her to attend a Normal School or College.

Old Boys Reunion: This photo shows details of life on Main Street in Watford in the early 1900s - patriotism, clothing styles and facades of Main Street. “Old Boys” reunions were a welcome home social activity to bring people back for fun activities that lasted for several days. Courtesy D Hollingsworth.

“Hello you, back home too” were the first words of a song by R. Dimond Swift, music by Clarence L. Cook, two local young men, for the Watford Old Boys’ Reunion, August 17, 18, 19, 20, 1924. No doubt as many girls attended the celebration as boys. Three special attractions come to mind. A pilot took people for flights in his biplane at $1 per minute. There was a baseball game between the old-timers and the town team…. On the last night, a dance was held on Main Street between Ontario and Huron Streets. A good time was had by all during the four days. The last words of the song were “Friends to greet. Watford Old Home Week.” ….

From our place we could see four churches, the Presbyterian, Congregational, English, and Baptist, and people going to them, and to the Roman Catholic and Methodist (on Erie Street at McGregor Street) Churches. During winter the ringing of the bells on the horses pulling cutters and the draught horses with their deep-toned bells pulling sleighs to the business area was most pleasant. The big logs on sleighs going by from the south to the saw-mill were looked at with great interest. A few times we saw horses running away.

Each day, Monday to Saturday, the town bell was rung at 7 a.m., 12 p.m., 1 p.m. and 6.p.m., and at 10:40 a.m. and 6:40 p.m. on Sunday. A person not at school could hear the High School bell, and on a quiet Sunday morning the bell of St. James Church on the Sixth Line was heard at our place. To let people know there was skating at the rink and for hockey matches and carnivals, a chap ringing a hand-bell came from the south. When the town bell, which is still at the top of the tower of the old fire hall on Ontario Street, was rung to indicate a fire, there was great concern.

Memories From the Late 40s and Early 50s

(submitted by Anne Janes McKay)

I enjoyed going to school in the winter time as each farmer would take turns picking us kids up and we would ride on the sleigh wagon with straw bales and lots of blankets to keep us warm. During the school recess, each child would be responsible to bring one can of soup. The teacher would bring the milk.

On Saturday afternoon and into the evening all of the families with children would bring a potluck dinner to Warwick Town Hall. That’s where I learn to dance — polka, square dance, etc. People played cards as well.

There was one winter, we had an ice storm. That’s when Dad was very sick with the flu so I had to take over the farm chores. I put ashes (from the furnace) on the ice from the garage at the house and all down the hill. We milked a lot of cows then. I needed some help and I called on Mac Tanton.

In the summer Mom made money by selling raspberries, gooseberries and strawberries from her garden. Dad had a shanty back in the bush where he made money by selling maple syrup. Mom would make lunch the night before. Dad would hook up the horse to the sleigh.

Shivaree

(submitted by Maxine Miner)

Shivaree. Now that’s a word one seldom hears now days, but a few years ago, everyone knew what it meant, especially if you’d ever lived in the country.

Shivaree. The very sound of the word could cause a newlywed couple to shiver. Because they knew that sooner or later they’d be the victims, just when they were least expecting it.

Just good clean fun for the most part, a country way of a warm welcome to a new bride or groom into the community. Now I’ve heard of some that got out of hand, tales of animals taken into the house, someone once turned a live turkey gobbler loose and it flew out the window taking the glass with it. Another case of the couple calling in the police but these were rare cases, I’m sure.

Most couples would have made some preparations of treats and bought in a few extra lunch supplies, coffee, and cold drinks. Alcohol hadn’t become so popular then. Other ladies would bring a few goodies as well.

Following a short time after a wedding and getting settled and then just when they thought they had gotten off free and were lucky, along they came.

Usually gathering at a central spot in great secrecy, they’d wait till the magic hour, when the couple would be in bed. Then it was time to go calling. Keeping silent until all had crept close to the house, there would arise such a din, anything that would make a noise, cow bells, dish pans, kettles to pound, with such a clanging. An old Buzz Saw blade hit with a hammer made a noise unlike any other. One had an old Model T horn and its ca ugga, ca ugga was heard for miles. Every dog in the neighbourhood of course joined in the chorus.

Meanwhile the rudely awakened couple was struggling to get into some clothes in the darkness and go open the door.

What a time of hilarity, while keeping the couple occupied, others were playing tricks, tying knots in clothes, hiding things taking labels off canned goods, putting strange things in the bed, and setting jellos in the bathtub. Sometimes there would be a blanket toss. The bride and groom in turn would have to lay on a blanket, strong arms would grasp the corners and toss them up and down. Soon coffee would be bubbling on the stove, while stories were told and silly songs sung. All good country fun. Those who’d found a chair sat, others sat on the floor. Furniture in the new home was still scarce.

The hours slipped by, as time does when your having fun. At last somebody would say it was nearly time to go home to start the morning milking, and other farm chores that were awaiting at other farms. Morning sun up wasn’t far off. The weary couple would grab a few hours sleep, before they started to sort out the mixed up clothes and clean up the kitchen, glad that this part of their early wedded life was behind them at last.

Crokinole

(submitted by Maxine Miner)

Many items of interest had found their way into our old kitchen on the farm over the years. But that day, long ago when that old crokinole board came, was a red letter day for all….

It was just a battered old octagonal-shaped board with crooked pegs and a well worn hole in the middle. But when the pegs were tightened and straightened, the nails tapped in all around the outside frame and it was given a good bit of polish, it became a real jewel to us kids.

It also came with a mismatched set of wooden buttons, probably homemade, as some were larger and thicker, and one had chips out of it, as though someone had taken a bite out of it. It was a little smaller then than rest, and we soon found out it was a natural for sliding in the centre hole, making a twenty.

As kids, Mom and Dad, too, we soon mastered the game, hitting our opponents’ men and leaving ours on, in a good scoring place. If you were lucky and your man went into the center hole, it counted as twenty points. But how sad if by some fluke your shot ended up sending one of your opponents buttons in there.

When we tired of the regular game of crokinole, we would shoot a few games of scrub. We’d set the buttons around in a circle and try to shoot off all the other players men first.…

I can still see my old uncle. He was partially blind. How he did love to play. He’d put his head down to the edge of the board and line up a shot. The buttons would fly. He was a crack shot. I know it was due to his patience with his young nieces and nephews that we all still love that game, and still play together.

I don’t recall that we ever played crokinole much in the summer, and the board would be put away in the closet for a few short months.

But as soon as the cool nights of Fall would come, it was crokinole time again. Sometimes there would be organized parties in our schoolhouse. What fun that would be for everyone. We’d all enjoy a super lunch after with lots of salmon sandwiches, Aunt Edna’s special Cream Puffs made with real cream, and hot chocolate.

Sometimes I wonder about today’s kids, sitting in front of the T. V., and all those strange games that go BEEP, BEEP, that I don’t understand. Is it really as much fun as we had with those old Crokinole boards of long ago?

Saturday Nights on the Town

(submitted by Maxine Miner)

When I was a child in the late 1930’s, Forest was our home town. Altho’ the little country store at Birnam supplied us with most of our needs, those weekly Saturday night trips into Forest were the highlights of a farm family’s week.

Altho’ we did not have a large selection of clothes from which to choose, mostly everyday things and our Sunday best, there was no excuse to appear in town looking like country bumpkins. Everyone was clean and neat. My mother always wore stockings, and our white shoes (leather back then, of course) would be treated to a fresh coat of “IT” shoe polish. Certainly no bare feet or sights of shirtless bodies were ever to appear on Forests streets then....

Our first stop would be at the Blue Water Creamery to drop off all the cream saved up all week and stored in a can in our cool cellar. Dad would carry it in and get an advance payment of a few dollars for Mother to purchase any extras needed. Later on he’d stroll back to pick up the grading slip and any other cash. Driving back up town, how lucky if we’d find a parking spot on the Main drag. Here one could just sit with an eye on the world.