Home Front to Battlefront (World War II)

Calla Janes, Eldon Minielly, Frances Minielly (Levi), Velma Minielly (Fraleigh) and Mary Janes (Pink) anxiously await the arrival of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth on a street curb in London in 1939. This photo was in the London Free Press on June 8, 1939. The hats and ribbons worn by the SS#1 students identified them as Twp., Lambton County pupils. Courtesy DB Weldon Library, UWO.

by Dr. Greg Stott

The Great Depression had a long and lasting effect on many people from . While many weathered the storm of economic uncertainty comparatively well, for others it would leave many lasting scars. As the 1930s progressed things began to improve. farmers:

began to gradually get better prices. Of course after being so flat… every little bit helped. And of course they really didn't get back on their feet… until the war started again. But some people, who had been working in Detroit, would lose their places and had to come back and live almost any place they could find to live around Arkona. And when the war started well they got work again… our neighbours, the Leggates, who lived in the Pressy home [South 1/2 of Lot 24, Con. 5, NER] next to us, he didn't have any work, and I suppose he [got] a lot of jobs here and there to do, but nothing in particular, because then he got a job building bridges in Eastern Ontario when the war started and she boarded the teacher and anything like that she could get to do.1

Yet even as the economic recovery began to be felt, other events overseas seemed to portend further troubles ahead. The Great Depression had been a worldwide phenomenon that had wreaked havoc with the global economies. The weakness of national economies had led to political unrest and upheaval and new political movements were born out of the fiscal and social chaos. Most notable was the rise of fascist dictatorships in Germany and Italy. Having officially secured its autonomy from Great Britain through the Statute of Westminster in 1931, Canadian diplomats were becoming well versed in the language of international diplomacy, and like their counterparts in other states were becoming increasingly alarmed by the militarism and rabid nationalism emerging from totalitarian states.2

The failure of the League of Nations to curb the expansionist demands of the Italian and German regimes seemed to render the world's democracies impotent. However, after failing to stop Italy's conquest of Abyssinia (Ethiopia) and Germany's remilitarization and annexation of Austria and then conquest of Czechoslovakia in 1938 and 1939, the world seemed poised for action. No longer beholden to follow Great Britain's lead, it was not clear what, if any, role Canada might take should another major conflict break out. Few doubted that, independent or not, Canadians would generally support Great Britain if war should result.

While the fervent imperialism that had fed Canadian excitement at the outbreak of World War I had largely dissipated, the affinity many Canadians held for Britain, as evidence by the reception King George VI and Queen Elizabeth had received early in 1939, was little doubted. (While the King and Queen did not deign to visit , hundreds of area school children and parents flocked into London to see them.) By the time the war ended in 1945, 1,086,343 Canadian men and women would have served full time in the Canadian armed services, of whom 42,042 would lose their lives. The nation would mobilize tremendous resources and transform the economy and society dramatically.3

It is difficult to know exactly how much the people of , Watford, Forest and Arkona were following the news in Europe and Asia in the late 1930s. Most probably heard about the growing designs of Germany's Nazi regime and many would have read in the newspapers and heard on the radio about the militarism of the Empire of Japan, especially as it resumed its brutal war against China in 1937. However, most were probably focused on their own daily lives and local concerns. As young farmer Russell Dunham explained:

I guess we didn't take it [the run up to war] as seriously maybe as some people. We knew things were a bit unsettled, and [in] Germany the Mark wasn't worth anything, and we heard about Hitler and all that, but we never thought too much about how it was going to affect us until it actually started.4

When Britain and France declared war on Germany because of Hitler's refusal to halt his invasion of Poland on September 3, 1939, the Canadian government held off its own declaration for a full week, to emphasize to the world that Canada was doing so of its own accord. As in the hundreds and hundreds of other communities across Canada, the people of had to adjust to the realities of another major conflict in less than a generation. While many worried about what war might mean, there were some immediate benefits to be felt. As the Watford Guide-Advocate informed its readership, the outbreak of war gave a major boost to the prices of livestock. The Guide-Advocate explained that “All records were broken on Saturday at the livestock auction when sale receipts reached $10,250. This is more than $1,000 better than any sale since the auctions were started.” The paper was hopeful in predicting that “[w]ith returns rising so much in recent weeks there is a possibility of that the total sale returns this year will exceed the $135,000 mark reached in 1937.”5

Within a few days of the declaration of war, nine Watford men and boys enlisted in the 26th Field Artillery in Sarnia and, having passed their medical examinations, departed to begin their training. There was a casualty of sorts in the earliest days of the war, for a highly anticipated addition to the Watford High School was shelved due to the new wartime realities.6

The fears engendered by war also reared their heads in the local press. In its weekly “Soliloquies” the Guide-Advocate noted that:

There are already indications that all the leniency and tolerance which Canada has extended to subversive elements in the country is coming to a sharp stop with the Dominion's entrance into Great Britain's effort to halt Hitler and his ideas.

A pervasive intolerance seemed to be completely justified by the new “emergency” situation, leading the paper to explain that Ottawa wanted to stamp out disloyal radical groups.7

Yet for all of the wartime posturing and stories of British travellers temporarily stranded in the Watford area because of the new crisis, most of the news remained markedly the same as it had been for weeks. The Bryce family reunion had been well attended at Reece's Corners on Labour Day, while it was announced that “[t]he regular meeting of Watford Women's Institute will be held at the home of Mrs. George Potter on Wednesday, September 13th at 8 o'clock. A good attendance is expected.” Indeed the war seemed to do little to affect the opening of a new school year for at Watford High School the reopening occurred “amid all the usual ceremonies and activities.” Meanwhile in the township the outbreak of war had not stopped Archie McLachlan of the Twelfth Line from moving to the old Luther Smith farm on the Second Line north nor the Women's Auxiliary and Guild of St. Mary's Anglican in Village from meeting at the home of Mrs. John Archer.8

Volunteer Civil Guard: On August 12, 1940, the Reeve of Twp. called a special meeting to consider the forming of a Volunteer Civil Guard in . Council agreed to form a Volunteer Civil Guard in connection with the County organization. They appointed Lloyd S. Cook as O. C. SOURCE: special meeting of Township Council minutes, Aug. 12, 1940.

After the invasion of Poland the war did not seem to amount to very much for the people of Twp. The world seemed to settle into an uneasy, if unofficial, peace. Early in March 1940, if the pages of local papers are any indication, it seems that most people in were interested in the investigations of geologists drilling on the Fourth Line looking for either oil or natural gas. That same month some 200 individuals showed up at Township Hall to view movies showing off winter sports in Quebec and Banff, Alberta, and logging in Canada's north. As one report explained “The feature films showing the poultry plant at Spruceleigh Farms at Brantford were particularly interesting, some in full color.”9

In the meantime Watford's Rotary Club teamed up with the Rotary Club of Watford, England, and received letters and publications from across the ocean. Well-wishers turned out to celebrate the fifty-third wedding anniversary of Mr. and Mrs. William Henry Luckham.10

The so-called “Phoney War” came to an abrupt end with the invasion of Norway in April 1940 and then the massive invasion of the Low Countries and France in May 1940. With alarming speed German forces smashed through defences and quickly subdued their enemies. Through what the Guide-Advocate called the “sobering truth” it became apparent that Canada was in for a more difficult time than many had predicted. Newspapers began to educate their readership to the realities Canada might face, and explained to them in detail about Canada's place in the British Empire and the world at large. Various editorials entreated local people and others across the country that all must do their part, warning many of the activities of the dreaded “fifth column” of saboteurs and the like who could wreak havoc on the war effort. Concluding one call to action the Guide-Advocate noted:

Make no mistake — although Hitler is striking desperately hard to break the Allies in one terrible smashing blow, we cannot believe the German horde will yet be stopped. But this past week of losses in Norway and Holland, and an anticipated crisis in the Mediterranean this weekend, brings home to Canadians in vital vividness the stand we must make, shoulder to shoulder with the Motherland.11

While few Canadians were directly involved in the fighting in the spring of 1940, some had a sobering connection. Watford's Daniel Steel learned through relations in Ireland that his brother-in-law J. Graham was a German prisoner of war, having been seriously wounded in both legs on the beaches of Dunkirk, France, where thousands of British and French troops had been stranded.12

Meanwhile just south of Arkona, as Russell Dunham recalled:

Dad decided to build a new woodshed, and the day Hitler went into France, Eldred Pressy drove by from Sarnia with the band (Eldred was a neighbour at one time) but he had Pressy Band in Sarnia and he drove down playing the band up in front of our place, when we were putting the roof on the woodshed and that was the day Hitler went into France. And people kept joining up. A lot of them joined up to give them some money, and they didn't have money before they joined up, they didn't have a job. And I had to go and take a test but they let me off for farm help.13

The situation seemed only to get worse. In June 1940 France, Britain's major European ally, sued for peace, leaving Britain isolated and increasingly vulnerable. Canada was therefore vital in helping to keep Britain supplied with not just war material but food and supplies to keep its population alive. This situation seems to have been a major spur to voluntary enlistments in Canada and in specifically.

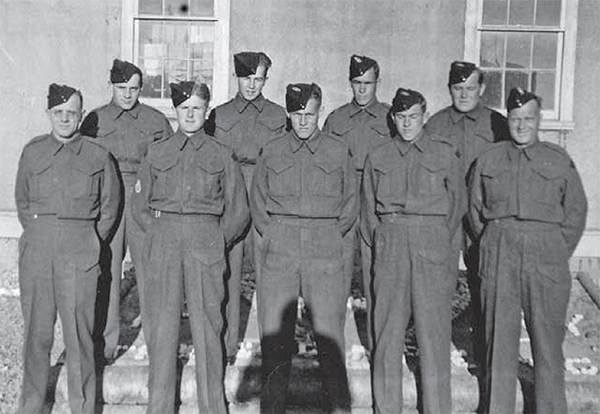

Arkona Boys Elgin Regiment: Front middle Lorne Dunham, back right Stanley Edwards. As in World War I, men enlisted to serve for a variety of reasons. Courtesy Arkona Historical Society.

For various reasons men and women increasingly threw in their lot with the war effort. The local Red Cross collected old automobile license plates so that the steel could be used in the manufacturing of vital components for weaponry. In December 1940 Watford's Red Cross volunteers packed their ninth shipment of supplies to be sent to war refugees via Toronto. The Watford supplies included “20 nightgowns age 12, 20 cardigans age 14, 25 pair mitts age 12, 25 boys shirts age 10, 20 pair children's sox age 4.”14

The very day that Hitler's invasion forces were unleashed on the Soviet Union — bringing Britain and Canada a crucial new ally — the Watford Guide-Advocate reported on a meeting of the Watford Rotary Club at which Rev. J. F. Bell of Point Edward Presbyterian Church assured the Rotarians that “Britain will survive.” But, it was noted, Canadians needed to contribute more money and resources to ensure the war was won. Bell explained that “Our men are brave — but they must have the tools of war! Planes, thousands of them, ships, guns, tanks — we need them all to stop this inhuman Nazi machine of brutality and death.”15

While in many ways the war was an inescapable fact of life, some facets of life continued on much as before. 's branch of the Junior Women's Institute and Farmers met regularly. At their May 1941 meeting:

Doris Minielly then took charge of the program and community singing was enjoyed, followed by the scripture lesson by Helen Morgan. The motto “Behind the Clouds is the Sun Still Shining” was given by Hazel Tanner. Eleanor Morgan favoured with a solo which was much enjoyed. A paper on “Nutrition” was given by Marguerite Thompson. Jean Jeffery gave a demonstration on “Clothes Closets Up-to-Date.” A social hour with the members of the Farmers club was enjoyed. Lunch was served and the National Anthem brought the evening to a close.16

Wib Dunlop in military reserve: Wib is the middle person in the second row. Courtesy W Dunlop.

Increasingly people were being encouraged to invest their money in “Victory Loans” as stories about bomb-ravaged Europe filled the dailies and weeklies. Many would later recall how radio programming ended with the jingle injunction to “Buy, buy, buy Bonds!”17

A further spur to action would come before 1941 was out. On December 6, 1941, the hydro was out in parts of Twp. for a large part of the day. When power was restored late in the day, farm families turned on their radios to hear the shocking news that the Empire of Japan had bombed American installations at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii.18 As a result the United States was soon fighting alongside Canada and Britain in a conflict that was now being waged in Europe and Asia. Immediate reversals and defeats for the Allies in the Pacific, and continued Nazi dominance in Europe, gave a certain urgency.

In it was reported that:

The December meeting of the “Willing Workers” for the Red Cross was held at the home of Mrs. Alex Westgate with 22 present. The financial and knitting reports were then given. The following knitting was then handed in: 2 scarves, 2 prs. service socks, 1 helmet, 1 turtle-neck sweater, 3 prs. seaman's long sox, 1 pr. mitts. The knitting for the year 1941 is as follows: 125 prs. socks, 68 prs. mitts, 16 scarves, 2 prs. wristlets, 10 helmets, 2 amputation covers and 16 sweaters. After the business the offering was taken and the afternoon spent in quiltig [sic]. The meeting was closed with the National Anthem and prayer. Next meeting will be held at the home of Mrs. Lloyd Eastabrook on January 2nd.19

Those involved in the military side of things were also fundraising as much as they could. It was announced that:

The 48th Battery is holding another popular dance in Watford Armoury Friday evening, December 19, to raise money for the Overseas Cigaret [sic] Fund. Music by Adam Brock and his orchestra. 75¢ couple. If you don't care to dance hand your contribution to any member of the Battery — every quarter will help send smokes to the boys overseas.20

As the war dragged on many of the things that civilians had long counted on or took for granted became harder to find. As industry turned over to war production, many staple goods were simply no longer available. As Canadian farmers and manufacturers churned out as much as they could to sustain their beleaguered allies and service men and women, Canadians had to do their part by tightening their belts and making do with less. The manufacture of automobiles went by the way, though even in early 1942 some were already thinking forward to the victory and noted that “By the time we lick the Nazis, the auto-buying public will not only be operating rundown jalopies but they'll be so tired of their old cars they'll be ripe for something brand new, out of this world!”21 Orville E. Wallis of Watford published an advertisement explaining the “Preference Ratings for Repairs” to readers of the Watford Guide-Advocate and explained “If we all co-operate as much as possible, we'll hasten the day of Victory and World Peace, when we can all get back to the happy care-free days of unrestricted motoring with New Motor Cars and plenty of gasoline for all.”22

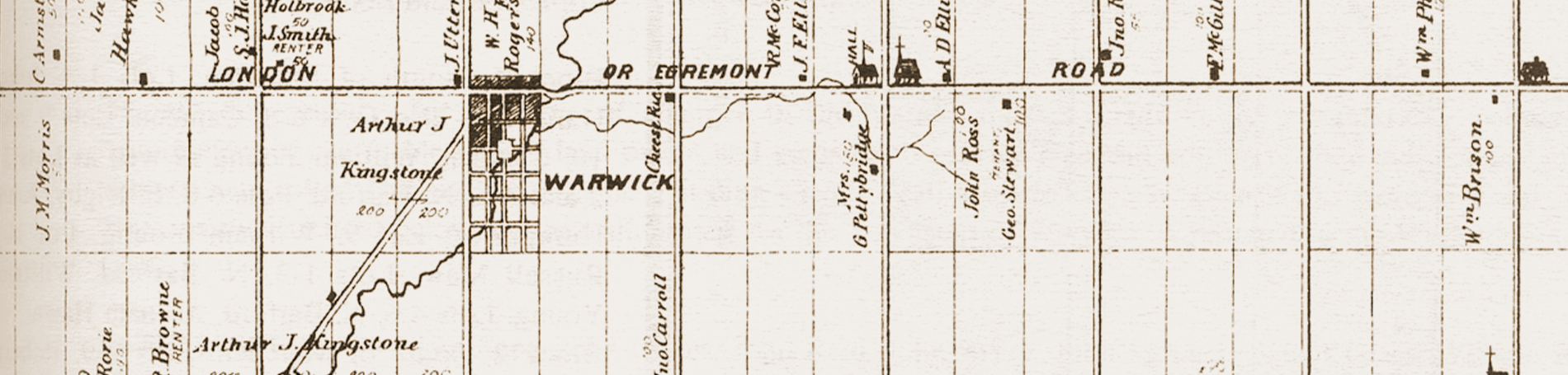

Farm boys in reserve, Warwick and Adelaide. Courtesy L Hall.

Everyone was encouraged to conserve and recycle and think about ways old items might be put to new uses. Watford's Boy Scouts were put into action to do their part; the local media reported that:

There is an urgent call for waste paper and cartons. Watford Boy Scouts will assemble on Monday afternoon and Tuesday morning, Dec. 29 and 30 to canvas the town. Come prepared to work hard and long for the sake of the cause! Citizens — your co-operation is desired. Have your papers, rags, iron and cardboard ready. Bottles will not be collected now. If you are overlooked phone 93. If you are in the country, bring in what you have soon and leave it at the Erie St. garage. The Scouts cannot cover the country, but will arrange to send the truck for a considerable quantity. This is urgent — Do your bit!23

Many youth during the period were encouraged to go out and collect milkweed pods, the fibres of which were used to stuff vests and for other products.

Increasingly the second page of the newspaper was filled with notices from the National Labour Board or advertisements from the Local War Finance Committees, harkening back to “pioneer grandparents” and running home the fact that “We've got a big job to do now!” In the summer of 1942 it was noted that Canada had a major shortage of nurses, and the paper outlined some of the worst atrocities then known to the public as a whole.24

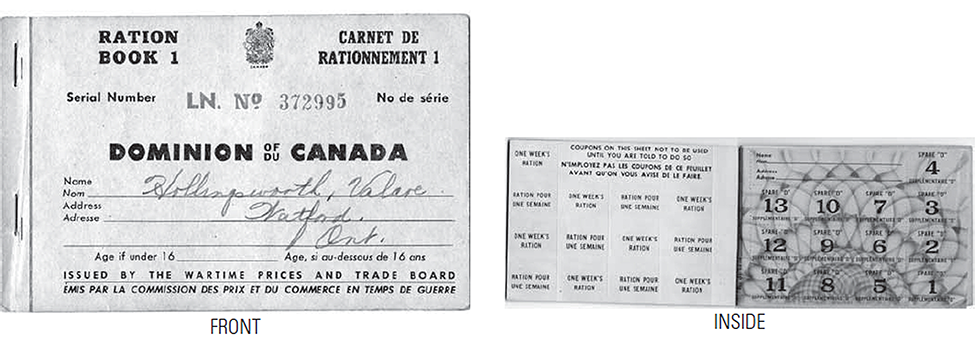

While gasoline rationing had come into effect by April 1, 1941, by May 1943 rationing was in full swing, as resources were tight and demand was high. Meat, sugar and gas were the rationed goods that were the most sorely missed. The local district had 2,710 applications for sugar with a total order of 175 tons, although ultimately the area was only permitted to have 44 tons total. It was explained that:

Certainly Canadians will have to devise other methods of preserving fruit for winter use, for like all other centres across Canada people in the Watford-Forest ration area applied for so much sugar the only fair basis will be extra coupons for canning at the rate of 10 lbs per person. The Local Ration Board is meeting this Thursday evening in Forest, and it is expected that canning coupons will go out by mail next week.25

There was one possible “bright spot.” It was noted that:

there is the grave possibility there will be practically no small fruit crops this season, particularly strawberries and raspberries and with continued cloudy wet weather there will be no cross-pollination by the bees or development of the fruit buds. Thus we shall have neither fruits nor honey, and we shall not need the canning sugar we cannot have!26

As one Arkona resident recalled “We didn't get much sugar or anything like that. Every tree in the town was tapped. The house was always full of steam because we boiled the sap.”27 Another resident explained that saccharin “was used a great deal.”28 Newspapers became filled with helpful hints on how to stretch rationed goods further, and how to find ready substitutes. Readers of local weeklies were provided with stories on how “Chemists Make Another Marvellous Discovery in the Realm of Synthetic Food.” Indeed it was hoped that “as much as a billion pounds of the product could be recovered annually by distillation from wheat.”29

Housewives had to contend with aging appliances with no hope of having them replaced. The Watford Public Utilities Commission urged that “[with] proper care you should get many years of service from your electric washer. So don't wait until it hollers for help. Have your electric dealer inspect it occasionally to see that it keeps running right.”30 Many residents would later recall that they had been unable to replace old appliances during the Depression, and had to make do with them until peacetime manufacturing could catch up to the demand, often into 1947 or 1948.31

High school students may have been too young to serve overseas but they were also expected to do what they could. The Dominion-Provincial Committee on Farm Labour called upon youth to “[t]hink of it, good pay… wholesome food… healthy environment. What better way could YOU spend YOUR vacation?”32 Many young women between the ages of seventeen and nineteen came into rural areas in droves to help during the summer harvest on the farms, to help with the increased production and depletion of farm labour as young men and women enlisted or pursued war-related work in the towns and cities.

While women, men and children across the township were engaged in “doing their bit” in terms of rationing, collecting, buying bonds and other war-related activities, they were also asked to step up to the plate and give something of themselves, quite literally. The Red Cross was continually calling for residents to come forward to donate blood, a desperately-needed commodity as the war progressed. In February 1943 it was announced that a mobile blood unit would set up quarters at the Watford High School and that in particular men were needed. It was noted that:

Miss G. Aikett, Red Cross technician in charge of the Mobile unit, will arrive in Watford Monday afternoon. Local Red Cross workers will assist in setting up complete equipment for the clinic. All former graduate nurses in the district are being asked to join with local doctors of Watford, Alvinston and Arkona, in lending their services, and the Red Cross ladies will serve breakfast to the donors as they are checked out by the nurses after their donation. Six donations will be taken each fifteen-minute period and donors are being notified of the time they have been allotted, so there will be no unnecessary waiting. For the first few visits of the clinic only men are being accepted — and many are so far hesitant about offering a blood donation. According to the Red Cross and medical authorities if you don't feel the need of more blood you can readily spare this small quantity.33

A month later it was reported that on March 16, 1943, a record number of men, 156 from Watford, Alvinston and Arkona, all between the ages of 16 and 65, attended the clinic. All of their names were printed in the paper.34

While the people of may have had to contend with some privations, news from abroad would have quickly dispelled any sense that they were being unduly affected. News reports about the suffering overseas frequently filled the papers. Locals who were serving overseas wrote home to inform people about conditions across the Atlantic. Alex McLaren wrote home about his experiences in England, explaining:

On the whole, conditions here are better than I expected to find them. The civilian population are all very busy with long hours at their regular work, plus extra duty two or three times a week on one of the volunteer services, most commonly the A.R.P. [Air Raid Precautions]. Urban and inter-urban buses and trains are very crowded, and these people must find the inevitable lining up and waiting a bit monotonous after five years of it. However, you hear very little complaining and at present the general mood of the public is a hopeful one — not over-optimistic, though.35

Writing from continental Europe Jack Gavigan explained that:

We are somewhere in France sharing a farmer's field with a flock of livestock, wheat, oats and barley. Of course there are the few French civilians, old men, women and children roaming around with whom we attempt to “parlez-vous” a bit. Already there are French classes organized in camp and we promise to learn how to ask for things, and perhaps even get our French in such a position as to be able to “parlez” with the French gals when we get to Paris or a town of some size.36

The war was not a high point for human rights in Canada. What transpired in Canada paled in comparison to the brutality and horrific atrocities occurring in Europe and Asia, but in a war being fought to preserve freedoms and democracy, the treatment of some minority groups failed to live up to these expectations. The fears expressed by local media and officials about subversive “fifth column” elements as early as 1939 succeeded in creating heightened suspicions. Numerous Italian Canadians were interned and, until the Union of Soviet Social Republics became an ally in 1941, numerous avowed and suspected communists were also imprisoned.

Alex McLaren, Air Force: Alex McLaren’s memories of World War II centred on being a member of the Royal Canadian Air Force. He was interviewed by Paul Janes in May 2006. The interview was transcribed by Janet Firman. Alex McLaren enlisted late in 1942 and started his training in Toronto early in 1943. Alex trained as a navigator and ended up on one of the Canadian Squadrons in Yorkshire as Navigator on Bomber Command for 433 Squadron when he went overseas in 1944. The following are excerpts from the interview. He remembered the friendships he made. We were very fortunate in our crew. It was made up entirely of Canadians from Southwestern Ontario, which was the most unusual thing. Most of the crews came from Newfoundland, British Columbia and Alberta. We ended up all in Southwestern Ontario, so that we were able to keep together after the war and there are still strong bonds of friendship. There are four of us still surviving. They are not that far away, like London, Trenton and Peterborough. We have certainly had some great times together and up until last year our crew had an annual get together at our homes or sometimes at a motel, resort or place of holiday accommodations. Alex also remembered the danger he faced in his Lancaster. On one of the Hamburg raids we were attacked quite viciously by the new German Messerschmidt 262 Jet fighters and they got a minor hit on our aircraft and fortunately the pilot through vigorous evasion action got away without any further damage. We had a hole through the spinner of one of the engines when we got back. Our gunners had a credit for a probable on that. We think we shot down the fighter, although it was not conclusive, but we got a probable on it. If you got airborne with a load of mines and a flight got recalled you just had to fly and fly and fly until you burned off enough fuel to get down to your safe landing weight…. Obviously it was dangerous. You didn’t want to hit it too hard when you came down. Although, after that the Hamburg flight I mentioned, we found out sometimes bombs hung up, they called it, sometimes it was freezing ice accumulation on hooks that held the bomb up and sometimes they didn’t release. The Bombardier had a little window he could kind of half see down to the bottom and see that everything was gone. It was not a very good observation place and sometimes they missed one. However, on this Hamburg flight we landed back with one five hundred pounder still in the bomb bay and when they opened the bomb bay doors it dropped out on the runway, but it didn’t go off because it was dropped safely. So you didn’t think about the danger…. Communication was censored. You had no way of knowing what percentage of losses were, all you knew that you lost one crew. … But, you remember the funny things…. SOURCE: interview with Paul Janes, 2006.

Mostly notably, however, in early 1942 — responding to pressures from British Columbia — the Canadian government ordered 20,000 Japanese Canadians removed from the Pacific Coast and moved to interior internment camps. This occurred despite the fact that the policy was decried by senior military and police officials and was widely condemned in eastern Canada. None of the internees was ever charged with disloyalty.37 As the war progressed many of the internees — who lost most of their property — were moved further east. Several of these families were sent to camps in Forest and Glencoe and were often seen to work in fields in and around . In the spring of 1943 one area farmer opted to “engage Japanese labor.” A telling report explained that:

A Japanese family, including husband, wife and three children arrived at the… farm recently and took up residence in a house on the farm. The husband, it is reported was born in Japan but is said to be a naturalized resident of Canada. Prior to the war with Japan he and his brother operated a shipbuilding yard near the municipal airport at Vancouver. With the removal of Jap families from the coastal area he and his family had to leave the area.38

Of course at home or abroad there were continual reminders of the toll that war took. In March 1943, the citizens of Watford received word “that Raymond Taylor, former High School instructor, who has been overseas as an observer in the RCAF [Royal Canadian Air Force], is reported ‘missing in air operations'.” As the Guide-Advocate explained “An interesting letter of his experiences on recent bombing raids was received just this week by one of his former students.”39

The number of casualties directly affecting the area rose dramatically once the Allies launched their massive amphibious invasion of France in June 1944. A week after this unprecedented assault on Hilter's “Fortress Europe,” word came to Watford that Francis Bowie had been seriously injured in the leg by a bomb fragment. It was explained that “Francis is the first Watford casualty reported from the Normandy beachheads of a week ago, and with many Watford boys in the same unit and with the hard fighting the Canadians have endured, many more such ominous notices are anticipated.”40 In August 1944, word reached Donelda Powell Phair and her young daughter Mary Ann that their husband and father, Lieutenant Ernie Phair, had “been reported missing in action in France on August 2nd.” Word would later come that Phair had been killed in action. Other families received grim, but less tragic news. Doris Moffatt McCormick learned that her husband Sergeant Alex McCormick “was seriously wounded and amputation of his left fore-leg had been necessitated.”41

Earl McKay, Artillery: Kenneth Earl McKay joined the reserve, the 48th Battery, in Watford in 1940, along with several other men from Watford. Shortly after, he joined the 55th Battery 19th Army Field Regiment attached to the 3rd Division (artillery) and went overseas. He returned in early 1946, when his son was five years old. Earl was interviewed by Paul Janes and Glenn Stott for this project in 2006. The interview was transcribed by Noreen Croxford. The following are some of his memories of World War II. One of Earl’s most vivid memories is that of landing on Juno Beach on D-Day. We didn’t have any maps or anything to show us just exactly where we were headed. We just set sail, perhaps around midnight, we just formed up and took off. When we were close enough, we were fi ring rounds, just like the Navy was fi ring. When we were first going in, we were fi ring all the way in from our landing craft. That was about 7:30 or 8 am. Those shells would go between 10 and 12 miles. It was rough going over. When we went in at 8 in the morning, the rudder was damaged on our landing craft, and we couldn’t steer to get in. Another landing craft had unloaded, and they put a tow line on us and towed us back out so they couldn’t hit us. We couldn’t land until 4 in the afternoon, and we should have been in there at 9 in the morning…. Lee Harrower repaired the damaged rudder so we could steer. I didn’t care if we ever landed at that time, but then we came in, and landed and then we had to fi nd the rest of the troop…. Out of A troop, out of 4 guns, I think there was only one that survived. So we found the battery and then took up positions. So by the time we found them, time was going on. We were busy fi ring the guns. I don’t know, the sun was shining, I even had my shirt off, and we were just fi ring, and throwing the shell casings overboard to get rid of them. I think Gus Edwards was on there, and one bounced back and hit me on the back, and just peeled the old skin off. The shells were hot. We were just busy and didn’t have time to think about it. They said if you weren’t scared, something was wrong with you. It was all new to us and we just took it. The Germans came over and strafed us that night. We went in on Juno Beach, and there were British on both sides of us. That map will show you that for the first few days, the Germans were in between the British and us. We didn’t get near as far as they figured we would get in. Another memory Earl has is that of fighting in the Falaise Pocket. I presume we were [on the east side], because when we went in, we had to go up around and back, to surround them. Yes, we should have been on the east side, but it always seemed to me when I was sitting up there, that I was facing the other way, but you can get turned around. We were sitting up top there, and we could look right down into town. Well, we were fi ring in four different directions… not sure if [we] were surrounding the Germans, or if they were surrounding [us]. I am not sure why, but that’s the orders we had. It tells in the book that we were fi ring north, east, south and west. SOURCE: interview with Paul Janes and Glenn Stott, 2006.

Many families had a direct connection to the war in Europe with letters coming from loved ones serving overseas. The local “Girls' Patriotic Club” sent parcels to those serving in Europe and received letters of thanks. Writing from her posting in England Connie Trenouth wrote:

Your lovely parcel arrived this week and you'll never know how much all was appreciated. For one thing… I was down to my very last bit of lipstick: And that Revlon is such a nice shade. Thank you all so much. Putting the picture in was a marvellous idea. I have looked at it so many times and thought how very good it was to see the familiar faces. P.S.: a lot of comments were passed about the good looking girls back there! Life here goes on quite as usual as far as work is concerned. The weather is perfect. I'm wondering what your March is like back there. We have taken to walking home through Hyde Park these evenings — they are full of bright spring flowers now and all the street vendors are selling daffodils, tulips, narcissi and violets. There is certainly no place like England in the Spring! Of course that doesn't include Canada! Best wishes to all of you — and thanks again.42

Writing to thank the Watford Rotary Club in August 1944, Bob Rawlings wrote:

In between the landing of the odd shell around here, I would like to try and thank you for the cigarets [sic] which I received July 11th. For awhile I wasn't sure just who would be smoking them, but Jerry has weakened and now we have a bit of relief so it is my chance to write. It's swell of you fellows to remember us so regularly and in a spot like this we sure appreciate smokes. I used to think my appetite came first but under fire those smokes hit the spot. So here is one fellow who is mighty grateful to the Rotary Club; long may you continue with your good work and all the luck to you in the future. I always knew you fellows did something besides smoke and tell stories, heh! heh! Wish I could tell you a lot about us here in return, but our censors forbid it, and besides your papers tell you more than we ever could. So this single letter will have to do the work. All the Watford boys here are in great shape and we hope to be back soon. Thanks again and God bless you all.43

Ray Prime and Earl McKay. Courtesy E McKay.

The end of the war brought jubilation. When the news arrived people poured out onto the streets. Many in the rural areas got the news over their radios. In Forest Lew McGregor recalled that a piano was commandeered from the Blue Moon Restaurant and pulled out into the street. Rollicking tunes were played as the dancing townspeople gave vent to their relief and joy. In Arkona, village children put bunting and flags on their bicycles and tricycles and formed a parade along Arkona's North Street through the village's main business section. The spontaneous celebrations gradually gave way to more solemn and organized remembrances. In Arkona a community-wide church service was held at the United Church with various village clergy participating. The Forest Standard reported that:

A victory celebration was later held in the Arkona ball park when citizens headed by the band, paraded to the park where a huge bonfire was lit and an effigy of Hitler burned. Fireworks and a community sing-song led by Mr. Weir completed the program.44

Watford had been planning formal celebrations a full month before the war in Europe ended, having struck a committee in April 1945. Rev. W. T. Eddy had already planned the order of service with the help of other local clergy, and hundreds of copies were sent to the printers weeks before the fighting had ended.45

For those families who had loved ones overseas the news must have come as a huge relief. Many reunions were impending. The war in the Pacific continued, and it was not entirely clear what Canada's role in that continuing conflict would be, but in the short term everyone was simply relieved that the long nightmare of war in Europe was over. However, as reunions occurred and were anticipated, not everyone was so fortunate. For one native who lived in Arkona, VE (Victory in Europe) Day brought false hope and then a devastating jolt: Magadalene (Sitter) Edwards recalled that:

My husband [Stanley] died… [t]hirteen days after the war. It was quite a thing when he died, he only died the day before he was coming home, you know, he was already to come home and of course he was killed. That was quite a shake up. My kids they were waiting for their dad to come home and people around their dads would come home… and Joan would say, “Will my dad look like that? Will my dad look like that?” and all this kind of stuff. And the preacher that was over at the United Church… he was a young man… he came walking out the front door and out the step and he was walking quite brisk up the street — it was the twenty-fourth of May [1945] — and I thought, “Well. What's he coming up the street for?” He walked directly to me and handed me this letter, “Your husband's passed away.” That's it. That's just how abrupt he was. And Fred Brown had been over to Thedford… and news came on the train that Stan had been killed, and so he came and got my Dad. And when this goof ball come over and told me that my husband was dead… [then] Fred and my Dad was here. I was pretty shaken… He handed me the telegram. Well, then the place just filled with people. It was the twenty-fourth of May and everybody had their boxes packed, and we were all going to Rock Glen for a big picnic, well everyone brought their boxes here and stayed all day…. They had a nice service in the church. It was quite a shaking experience…. But I weathered it through. I raised two kids and got them educated.46

Slowly other service men and women began to trickle home as the conflict came to an end. In Forest the community newspaper urged people to come and celebrate at a special VE Dance to be held at the Forest Armoury on June 11th until the wee hours of June 12th with Ken Williamson's orchestra. “Proceeds all for the Local Boys' Box Committee.” The admission was set at 50¢ for civilians while those in uniform paid 35¢.47

The inhabitants of Village played host to two of their own who had had harrowing experiences during the conflict. The Watford Guide-Advocate reported that

On Sunday evening, a large crowd attended the Village United Church to hear Percy Harris and Clarence Wilkinson relate their experiences as members of the RCAF and as prisoners of war in Germany. Both outlined their treatment in the prison camps and spoke highly of the Red Cross and the parcels that arrived regularly. If it had not been for the food parcels it would have been impossible to survive on two slices of bread in the morning, soup at noon and bread again at night. The collection totalled $45.00 and will be forwarded to the Bombed Out Churches in Europe Fund.48

The local population could look to their record during the conflict with some pride. Having suffered comparatively little they had been able to contribute much. In the local bond drive Twp. had set a goal of raising $140,000 and they ultimately reached nearly 95 percent of their goal with $133,550. Watford had set for itself a goal of $135,000 and had surpassed it by raising $152,950, while Arkona raised an astounding $65,000, a full $25,500 more than their goal. Forest had hoped to collect $150,000 but surpassed expectations by raising $196,000.

As the dust settled there were chances for the people of to look back at their efforts and look forward to the post-war world. The relief and joy that had marked the end of World War I in 1918 had fallen in the midst of the devastating influenza epidemic and been followed by a serious post-war depression. While the transition to a peacetime economy after World War II was not without its bumps and hiccups, the serious economic difficulties that many had feared would repeat themselves did not occur.

The end of war in 1945 was undeniably a major international watershed, but while perhaps less obvious, it was also one for Twp. too. The war brought about a mobilization of people and goods like never before. It led to an unprecedented mechanization of agriculture and industry that would only accelerate in the succeeding decades. The war had provided work and opportunities for many men and women, especially 's youth, and these experiences would lead many to find new pastures leading them away from their rural homes. Post-war influxes of immigrants from war-torn Europe would take their places, but there was a profound shift and the changes would transform and its environs dramatically.

Arkona at the end of World War II: People of all ages celebrated the end of the war. Courtesy Arkona Historical Society.

Kris Boyd: Sergeant Kris Boyd, a reservist with Sarnia First Hussars, graduated from North Lambton Secondary School in Forest and sought out a career that offered both adventure and excitement. He joined the United Nations Peacekeepers and found himself in Bosnia in 1994. The role of the peacekeeper was to keep the three fighting factions apart. They were stationed at check points and observation points. Kris said “They would fight around us. When they shot at each other, they had to shoot through us!” Boyd talked about how the Peacekeepers would help rebuild schools. On one occasion, he and other Peacekeepers were delivering desks to a village school. The Peacekeepers had a tour of the school and an opportunity to look at student art hanging on the walls. “The pictures at first appeared to be typical artwork of third grade students. However, at second glance, they were very disturbing. The grass was brown, the sky was gray, the trees were devoid of leaves and stickmen people lay on the ground in a pool of blood.” Down the corridor hung a child’s artwork with blue skies, green grass, flowers and a bright sun shining behind a castle with a Canadian flag waving in the breeze. “I believe that people see the military as a sign of hope. The young artist saw hope and his artwork reflected that hope. It was no accident that he drew the fl ag of Canada. The Canadian fl ag has and will continue to offer hope around the world,” said Sergeant Boyd. Trooper Boyd was one of 55 Canadian Peacekeepers who were detained by the Serb army in late 1994. For 15 days Kris was caught in a political tug-of-war that captured the world’s attention, yet drove the young soldier to boredom. They were held in a small house with nothing to do. “It was customary for the Ser bs to sit with us each day for one hour for a coffee and a smoke and to talk about the situation,” he recounted. Serving as a military ambulance driver, Trooper Boyd and three other soldiers were allowed to leave the observation post one day to transport an injured soldier to the Canadian camp in Visoko. The Serbs granted the release on the condition that they return to their observation post. Despite the everyday dangers of his assignment, Trooper Boyd says he has no regrets about volunteering for the mission. “It’s an excellent experience and it’s one I’ve always wanted to have,” he said. “When I had the opportunity to join I jumped at it and I don’t regret it all.” When Kris returned to Canada he took up residence in Sarnia. Kris is the son of Doug and Shirley Boyd, Quaker Rd., Twp. SOURCES: Pearce Bannon, Th e Observer, Sarnia, December 10, 1994 John Lawton, The Observer, Sarnia, Nov. 8, 2005.

Ration books were required for many items during WWII. Courtesy D Hollingsworth.

List of Veterans:

| Forest Cenotaph |

|

1914–1918 Joseph W. Cole Frederick Core M.M. Charles E. Cole Dr. Arthur E. Lloyd John M. Patterson Ellsworth Rogers Walter Venneear John L. Warwick Orville K. Wilson Gordon Ellerker John W. Coultis Harry Jennings 1939–1945 Oliver C. Brandon Lloyd H. Bressette John K. Brown Harold D. Durrant Ivan J. Garret Vincent J. Hubbard Harry A. Keast William H. Leonard Donald H. McRae W. Penri Morris Allan F. Penhale Thomas H. Rothwell Francis B. Thaine Herman F. Thomas Walter G. Ward W. Douglas Moody |

| Arkona Cenotaph |

|

1914-1918 Pte. Gordon Paterson Lance Corporal Roy N. Fair Pte. George Puttick Pte. William Torrington Pte. Clarence F. Jackson Pte. Gordon F. Brown Pte. James E. Zavitz Pte. Harry Wilcocks Pte. William Maybury Corporal Beaumont S. Flack Pte. Fred R. Brown Pte. J. Edwin Crawford Lance Corporal O. F. Cameron 1939-1945 Stoker W. Norman Roder Pte. Eric J. Smith Pte. Stanley A. Edwards Sgt. Frank Shadlock Rifleman E. D. Butler Trooper R. McAdam Stoker J. Foran Pte. S. Ackleton Sgt. Gordon F. Utter. |

| Watford Veterans - World War II, 1939-1945 |

|

Royal Canadian Navy Army staff clerks Harry Fuller Wellesley Sisson United States Army John Bruce James Corsaut Richard Moore 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion George Brown Donald Bryce Forestry Corps George Lawrence Army Dental Corps Donald McCaw Jack Woods Royal Canadian Signals Philip Kersey Bryce Jeffrey Gordon Minielly C.W.A.C. Catherine Case Jean McGill Laura Noxell R.C.A.F. (W.D.) Evelyn Gilliland Annie Hick Margaret Johnson Dorothy Petersen Mons Stapleford, N.S. Constance Trenouth Army Chaplain Rev. Fr. Bricklin Rev. Walter J. Gilling Rev. Alex Rapson Rev. John Bonham Army Pay Corps Robert Bruce Cecil Hollingsworth Army Postal Corps Keith Acton Ken I. Fulcher Lee Mitchell Veterans Guard L.H. Aylesworth Ivor Blunt Lloyd Cook Sandy Downs Orville Edwards Roy Lawrence Jack Stapleford Army Provost Corps Eugene Beattie Hugh Fair William Gilling Don Preece Don Richardson Fred Taylor Eric Thompson Infantry Bernard Barnes Harvey Blunt Jim Case Stan Clark Carl A. Class Ross Collins Leroy Dann Edward Dolan James F. Elliot Anthoy Fadelle Harold Grondin Clifford Harper Laverne Harper Bruce Main Jack McGillicuddy Percy C. Mitton Kenneth Morgan Ken Muxlow Neil Patterson Jimmie Prangley W.R. Prince Ward Smith Clayton Stewart Cecil Sturgeon Albert Swartz Claire Taylor Paul Westgate Ray Westgate Basic Training Instructors Donald Aylesworth Willis Dell Mac McIntosh Annie McVicar Ernest Phair Frank Prangley Army Medical Corps Margaret Burchill Dr. Wm. Coke Dorothea Kersey Dr. Ernest McKercher Cecil E. Parker Dr. Ross Parker Clifford Schram Gerald Willer Army Service Corps Lloyd Bryson Jack Callahan Jack Colburn Lawrance Cooper Alvin Doyle Alex Galbraith Ray Gavigan Laverne George Alex McCormick D. Ross McEachern L.J. Millar Stan Parker William Richardson Elmer Woods. Royal Canadian Engineers William Blunt Walter Bradley Frank Collins Dick Elliot Donald Fleming George Howsam Jim Jones Kenneth Inman Harold Manders Ernest Sitlington Willard Smith Nelson Stapleford Norman Turner Gordon Willoughby Armoured Tank Corps Lester Allen Jack Brand Lorne Goodhand Donald Leach Verne Leach Jack Lusk James Prangley James D. Prince Ralph Shaw Harvey Stapleford John W. Sturman Gerald Swan Ordnance Corps Wilfred Aulph J.D. Bryce Ed Burns Jack Coupland Keith Cowan William Fitzgerald Wilbert Garside Everett Garson James Gavigan W. Frank Hick Harold Howden Ross Hume D. Laverne Kersey William Leach Ralph Learn Ken Mansfield Clare McIntosh Alex McLean Leo McManus William Parker Gordon Redmond Clare Roche Jack Rogers Bernie Smith Harold Sutton G.G. Swan Bert Willer Ivan Williams James R. Westgate Royal Canadian Artillery Ross Atchinson Oliver Alton Keith Aylesworth Lloyd Barnes Charlie Bidner James Blezzard Francis Bowie Allan Brown Harold Brown Howard Brown Fred Burgess George Carroll Jack Charlton R.A. Clark Max Clements Norman Cosens Lyle Cundick Johnny Dolan Cecil Dolbear Bill Edgar Dick Edgar Donald Edwards George Edwards Ray Edwards Walter Edwards Allan Fair Archie Fleming Mike Fraser Bill Furlonger Jack Garside J.J. Gavigan Michael Glennon Alvin Good Elmer Goodhand William Gregory Lee Harrower Donald Harper Gordon T. Harper John R. Harper Harold Haskell Roy Haskell Clarence Healey Eddie Hewitson Clarence G. Jackson Bert Kersey Jack Kersey Fred Kidd Dalton King Albert La Ferriere John Lockridge Burt Lucas Melvin MacGregor Warren Marshall Don B. McChesney Earl McKay Jack Newton Jim Orrange Ivan Parker Bob Rawlings Allan Resorick George Richardson George Roberts Lloyd Roberts Allan Robertson Robert Routley Clarence Sharp Harry Sitlington Dave Smith Robert Smith Gordon Spalding Arthur Stapleford Edwin Stapleford Fred Stapleford Norm Thomas Gay Turner William Turner Douglas Urie Tony Van Dinther Edward Williams Harvey Williams Laverne Williamson Royal Canadian Navy Harold Barnes Adeline Evans Gord Gare Eugene Grondin Donald Harrison Ted Hayes Gordon Henderson Robert Hollingsworth Basil Just Donald Kersey Roy McIntosh Elmer Minielly James Moon Dan Orrange LaVerne Routley Forbes C. Rutherford Leon Sisson Ralph Steadman Howard Swales LeRoy Swales Elmer Swan Stan Wallis Harold Willer Royal Canadian Air Force Andrew Aitken Clarence Cable Jack Caldwell Clare Callahan P. Avery Dodds Russell Down Ivan Edgar J.D. Edworthy William D. Ellison Leo Gavigan John Gribben Keith Hollingsworth Bert Inman Earl Janes Allan Jeffrey George Kingston Ross Laws James Lett Doug Mansfield Alex McLaren Lyall Mercer Frank Michie Harley Moon Jack Orrange Gordon Parker Winston D. Parker Roy Roberts John Ross Asil Routley Jack Rowlands Alfred Sharp Glen Shea Lyle Sitlington George Smith Donald Spalding Harper Spalding R. Laird Stapleford William Swan Ray Swartz Donald Tait Jack Taylor Raymond Taylor Donald C. Thomson Raymond Thompson Don Vail Neil Westgate Palmer Westgate Clarence Wilkinson Lyle Willer

SOURCE: The Guide-Advocate |

| Watford Veterans - Korean War, 1950–1953 |

|

Myles Fitzpatrick Bob Hayward |

| Currently Serving Our Country |

|

Joel and Rose (Coates) Bergeron Michael Butler Jeff and Kim Brush Brian Brown (Retired). |

Endnotes

These links were used at the time of publishing in 2008. Some links may have changed or may no longer be active.

1. Russell Dunham, interview, October 12, 1997.

2. Norman Hilmer, “Statute of Westminster,” Canadian Encyclopedia, Second Edition, 1988, p. 2074.

3. C. P. Stacy, “World War II,” Canadian Encyclopedia, Second Edition, 1988, pp. 2344–2346.

4. Russell Dunham, interviews, October 12, 1997, and November 23, 2000.

5. Watford Guide-Advocate, September 15, 1939.

6. Watford Guide-Advocate, September 8, 1939, and September 15, 1939.

7. Watford Guide-Advocate, September 8, 1939.

8. Watford Guide-Advocate, September 8, 1939.

9. Watford Guide-Advocate, March 8, 1940.

10. Watford Guide-Advocate, April 26, 1940.

11. Watford Guide-Advocate, May 17, 1940.

12. Watford Guide-Advocate, October 25, 1940.

13. Russell Dunham, interviews, October 12, 1997, and November 23, 2000.

14. Watford Guide-Advocate, December 6, 1940.

15. Watford Guide-Advocate, June 6, 1941.

16. Watford Guide-Advocate, June 6, 1941.

17. Watford Guide-Advocate, June 6, 1941. Russell Dunham, interview, undated.

18. Russell Dunham, interview, December 2004. Interviewed by Greg Stott.

19. Watford Guide-Advocate, December 12, 1941.

20. Watford Guide-Advocate, December 12, 1941.

21. Watford Guide-Advocate, July 31, 1942.

22. Watford Guide-Advocate, February 5, 1943.

23. Watford Guide-Advocate, December 19, 1941. The same issue reported that “Goebbels must be hard put to it for a satisfactory story explaining the large-scale German retreat in Russia. Couldn't he just say the army is coming home for Christmas?”

24. Watford Guide-Advocate, August 14, 1942.

25. Watford Guide-Advocate, May 21, 1943.

26. Watford Guide-Advocate, May 21, 1943.

27. Magdalene (Sitter) Edwards, interview, August 14, 2007, Arkona, Ontario. Interviewed by Greg and Glenn Stott.

28. Janet Firman, notes, “War & Depression.”

29. Watford Guide-Advocate, October 1, 1943.

30. Watford Guide-Advocate, October 1, 1943.

31. Russell Dunham, interview, undated.

32. Watford Guide-Advocate, May 17, 1945, and April 26, 1946.

33. Watford Guide-Advocate, February 5, 1943.

34. Watford Guide-Advocate, March 19, 1943.

35. Watford Guide-Advocate, August 11, 1944.

36. Watford Guide-Advocate, August 11, 1944.

37. Ann Sunahara, “Japanese,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, Second Edition, 1988, pp. 1104–1105. Patricia E. Roy, “Internment,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, Second Edition, 1988, pp. 1083–1084.

38. Watford Guide-Advocate, May 21, 1943.

39. Watford Guide-Advocate, March 19, 1943.

40. Watford Guide-Advocate, June 16, 1944.

41. Watford Guide-Advocate, August 18, 1944.

42. Watford Guide-Advocate, August 11, 1944.

43. Watford Guide-Advocate, August 11, 1944.

44. Forest Standard, May 17, 1945.

45. Watford Guide-Advocate, April 6, 1945.

46. Magdalene (Sitter) Edwards, interview, August 14, 2007, Arkona, Ontario. Interviewed by Greg and Glenn Stott. See also Forest Standard, May 31, 1945.

Subscribe to this page

Subscribe to this page