From Farm Field to Battlefield (World War I)

Second from left Russell Duncan, then Walter Duncan, May 1918. Courtesy H Van den Heuvel.

by Dr. Greg Stott

In the spring and early summer of 1914 there were few portents that war was about to engulf much of the western world. In London, England, most of the politically-astute classes were interested in the perplexing question of Irish Home Rule or confounded by the militant stance of women suffragettes. In much of Canada people were concerned with the everyday goings-on in their own lives, and so it was in Township. In their home just south of Arkona, farmers Colonel and Lorena (McChesney) Dunham still grappled with the costs incurred by major house renovations necessitated by the Good Friday storm of 1913. Earlier that year Lorena had complained that “you cannot build now for nothing it takes a penny or two what we have done took $600.00.” The news that the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne had been assassinated in the much-contested region of Bosnia probably received little comment from most of 's population, although it was covered in the local weeklies and the London and Sarnia dailies. The resulting crisis, whereby Austria made impossible demands on tiny Serbia, which received backing from its chief defender Imperial Russia, must have seemed impossibly far away to most people in Watford and Village.

Politics was a concern for the enfranchised of , but not at the global level. As the Watford Guide-Advocate informed its readership, “The voters' list of the Township of for 1914 is now in the hands of the Clerk, and copies can be had for the asking.” It was further warned that all potential voters should ensure that any omissions or corrections be brought before the clerk “in writing before 29th of August.” The list, not amended, “ contains the names of 1036 persons entitled to vote at municipal elections and 861 entitled to vote at elections for the Legislature.”

At the Butts' Goderich Camp. Courtesy D Hollingsworth.

While Austria assaulted Serbia with the backing of Imperial Germany, Imperial Russia took aim at both Germany and Austria on behalf of beleaguered Serbia and Germany mobilized against Russia's ally France. Meanwhile the people of marvelled at the strawberry plant grown by farmer George Ott near Arkona. The plant, grown from seed, had gone on to produce an astounding “one hundred and fourteen berries, the largest measuring 5¼ inches in circumference.” On July 31st — the very day France prepared to face Germany in a military showdown - the readers of the Guide-Advocate were treated to the news of E. E. Baladon of Medicine Hat, Alberta, and his visit to Watford, and how the topic for that coming Sunday's meeting of the Epworth League of Zion Methodist Church, under the direction of T. H. Fuller and Clayton Edwards, was to be “How May I Demonstrate in this Day the Lordship of Christ?”

Curiously enough there was some local military intelligence relayed to the Guide-Advocate's readership. As the paper explained, the local 27th Regiment would “go under canvas at Goderich two weeks from next Monday.” With not a hint of irony it elaborated that “The training this year will be of a most interesting nature.” The article merely asked that “All officers and men are requested to attend the armoury on Friday evening at 8 o'clock sharp for instructions.” Given that the 27th was to be under the leadership of a veteran of the illustrious Scots Guards, it was reasoned “that the Twenty-Seventh will be the crack regiment at the Goderich camp.”1

As July lapsed into August matters took a dramatic turn. When France refused the impossible concessions demanded by Germany, the German army smashed westward to attack France by crossing into Belgium and violating that country's neutrality. Beholden by a decades-old treaty to protect “Gallant Little Belgium,” Britain was outraged by this violation. Ultimately British demands that Germany remove itself immediately from Belgium went unheeded. As a direct result, on August 4, 1914, Great Britain was at war with Germany. The people of Twp. in Lambton County, in the Province of Ontario in the Dominion of Canada, by virtue of being part of the vast British Empire learned that, as a result of this faraway provocation, they too were at war.

It is difficult to gauge exactly what the reaction of most citizens of was to the news. In the lead-up to August 4, farmer Stephen Morris continued to record the daily activities of his family. On the day war was declared the 46-year-old farmer recorded only that “We drew in our oats (14 loads of oats).” War or no war, the Morris family continued to finish with oats the following day. Morris' continued preoccupation with the farm and the goings-on in the neighbourhood did not allow foreign intelligence to creep into his record. He did make note of the death of his wife's uncle and noted that on the night of October 26 “it snowed 13 inches on the level. We had our cattle in the stable for two days and then turned them out again.”2

Meanwhile, not far from the Morris farm, eighteen-year-old Russell E. Duncan kept a detailed record of his daily activities throughout the spring of 1914. Even a special royal occasion did not mean a break in farm routine. On June 3 Duncan recorded “Fine and warm, raining steady tonight. Worked at fence the Kings birthday a holiday.” Duncan did allow himself some fun for two days later he noted that “I went down to Kingscourt and played football….” On the actual day war was declared he penned in his diary, “Fine and warm drew in 8 loads of oats. Father & I went to picture show tonight, War Scare in Europe.”3

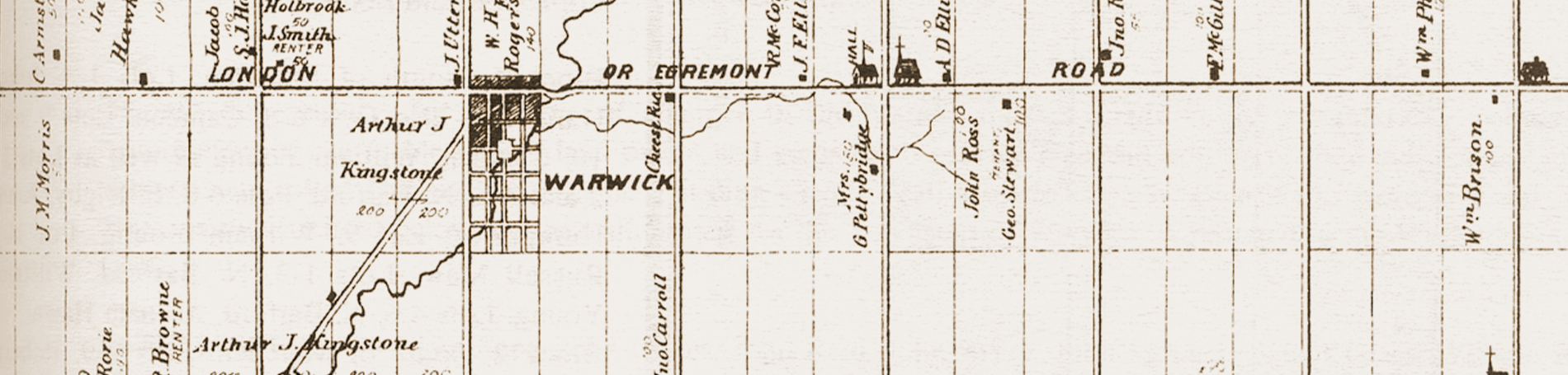

Certainly the news for August 7, 1914, containing references to the goings on in the township and surrounding villages, differed little from that of July 31. Readers of the Watford Guide-Advocate learned that A. E. Archer had sold his 100-acre farm on the Egremont to Peter Ferguson for $6,300 and removed to Plympton while “Misses Jean and Edith McCormick, Kingscourt, are spending a couple of weeks with friends in Mitchell.”4 There was comment, of course, and it would be a mistake to assume that the war passed without acknowledgement. In an editorial from August 21, 1914, the Watford Guide-Advocate sounded a sobering note when it explained:

When a war breaks out, we fondly think it is good for trade, and very profitable for those who keep out of it. We do not consider what it costs mankind and how well the burden is distributed. Of such a war as this, with all the great powers involved, it would be a very low estimate to put the direct cost to the public treasuries at ten million dollars a day – twenty would be a better guess – besides all the destruction of life, limb and property, that would not come into this count.

Another editorial piece noted that while it was commonly held that kings made war, the fact was that “[the] midsummer madness seems to seize upon men” from all walks of life. It concluded that:

It may be that war has a mission to bring in the coming era of peace with a bridal dawn of thunder peals. But, so far as can be seen, the very opposite has been, and must be the fruit of war. Autocracies have always fallen back on war as their natural reviver, and war has always left trails of vengeance behind it.5

For nine-year-old Florence Austin on her parents' farm in the south-eastern corner of Arkona, the news was not entirely understood. On the morning of August 5 she found her father, local greenhouse operator Philip, and their hired main Will Torrington, standing in the front yard with the London Advertiser spread between them, the headline screaming that Canada was at war. That spring Florence had planted her own small garden of flowers and vegetables and, like older horticulturalists and farmers alike, was perplexed by the serious infestation of army worms that threatened gardens and crops alike. Farmers around the area did what they could to smite this natural enemy by ploughing deep furrows around their threatened crops to stem the advance of the worms. Confused by the rhetoric of war and the menacing army worms, Florence attempted to trowel trenches around her own garden, having half convinced herself that the monstrous Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany had conjured up the army worms to hurt the people of Twp. She later noted that she and her schoolmates became fond of chanting “Kaiser Bill Went Up the Hill to Take a Look at France / Kaiser Bill Went Down the Hill with Bullets in his Pants.”6

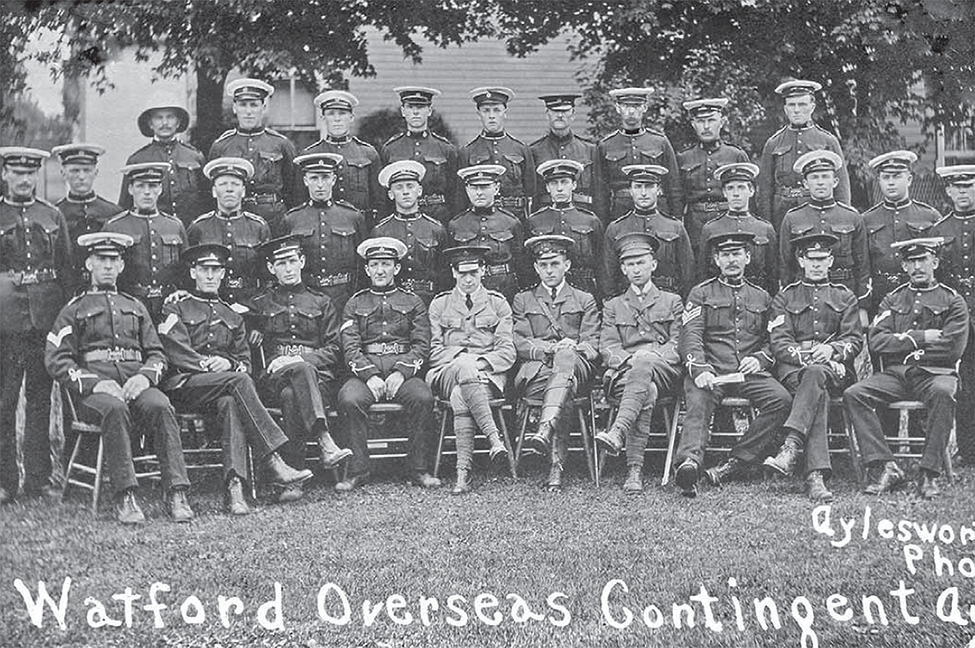

Watford Overseas contingent, 1914: Patriotism was very high, as was the sense of adventure “For King and Country.” Courtesy D Holingsworth.

As far as the fighting of the war and the crimes and intrigue of the German Kaiser were concerned, army worms paled in comparison to an apparent spy tower built in the heart of Twp. While the details are vague, various stories are told of how, not long before the outbreak of war, some strangers to the area — often described as “foreigners” — approached farmers in the vicinity of the Wisbeach post office about renting land to construct a tower. Ultimately a wooden observation tower was constructed on the hill at Wisbeach, providing a commanding view of the surrounding countryside. The builders of the tower apparently disappeared shortly after its completion and seemingly never returned. It did not take the loyal inhabitants of the township long to surmise what had been afoot: the builders of the tower had almost certainly been agents of the German government, bent on spying and gaining all sorts of important wartime intelligence about the comings and goings of the local farming population! What important secrets vital to the British and Canadian war efforts were to be gleaned from have never been elucidated, but in the fevered paranoia and xenophobia of the Great War, suspicion, however outrageous, was often as good as proof.

By the second half of August 1914 the citizens of and Watford and their zeal for supporting the conflict had solidified. As the Watford Guide-Advocate informed its readership:

The seriousness of the war has been strongly emphasized to the people of Watford and vicinity during the past two weeks. Recruiting for the overseas contingent had been going on quietly, but on Wednesday of last week when the order came for the men to mobilize and they were put on the militia pay roll, people began to think that war matters were affecting us right at home. Daily since then six hours drill (by Drill Sergeants Davies and Owens) has been the order, and the sound of the bugle on our streets morning, afternoon and evening tended to remind us that every preparation was being made by the local militia to support Britain in her justifiable war for the preservation of the liberty of her subjects.

People from most walks of life came out to show their support to the militia. Rev. W. G. Connolly, who had served as part of the “third South African contingent” during the Boer War, “tendered to the men some very sound advice and many useful hints as to their conduct while in the King's service.” The fifty-strong militia company marched from the armoury to Trinity Anglican Church on August 16 for a service with their honorary chaplain Rev. S. P. Irwin. The Guide-Advocate recorded that:

The sacred edifice was crowded to the doors, many worshippers standing in the vestibules. The interior of the building was profusely decorated with flags. The scene was a bright one, the full dress uniforms of the soldiers and the white surplices of the choir lending a touch of attractiveness that was pleasing to the eye. The service was most impressive in its character, special prayers for the troops and for victory over our enemies were used, the processional hymn was “Fight the Good Fight” and the recessional “God Save the King,” in which the congregation joined with a lustiness never before heard in Watford… The smart uniforms, the flags, the soldierly bearing of the officers and men helped to intensify the solemnity of the occasion and many hearts were filled with silent prayer for the safe return of the gallant men who were going to the front to defend our King, homes and country.

Laying cornerstone of Watford Drill Hall: A high point of Imperial devotion. Courtesy Watford Historical Society.

As the enlisted marched from the church back to the armoury “[t]he streets were lined with rigs and autos and the sidewalks crowded with people.” Contingents of men from Sarnia and Petrolia arrived by train on Wednesday, August 19, escorted to the armoury by Watford's band. As the local paper described it:

On Thursday morning at 7:43 the company entrained for the east. Notwithstanding the early hour and a heavy rain shower, a large number of people went to the depot to see them off. The train pulled out amid cheers from the spectators, and the band playing God Save The King. May they return without seeing active service, but should it so happen that they are called on to fight may they come home singing : -

And when they say we've always won,/ And when they ask how 'tis done,/ We proudly point to every one/ Of England's Soldiers of the King.7

Other than during the heady days leading up to the grand send-off, for the most part the people of were not directly affected by the war. It was, after all, a conflict largely fought in the trenches and battlegrounds of Europe with a few other international entanglements. Certainly there was war news to be had. Families that took dailies from London or Sarnia would keep on reading the incessant reports from the front. Many school children recalled that, in addition to learning patriotic songs to help “King and Country,” teachers would often read to them the war news, talking of the marvellous advances of British and Canadian troops.

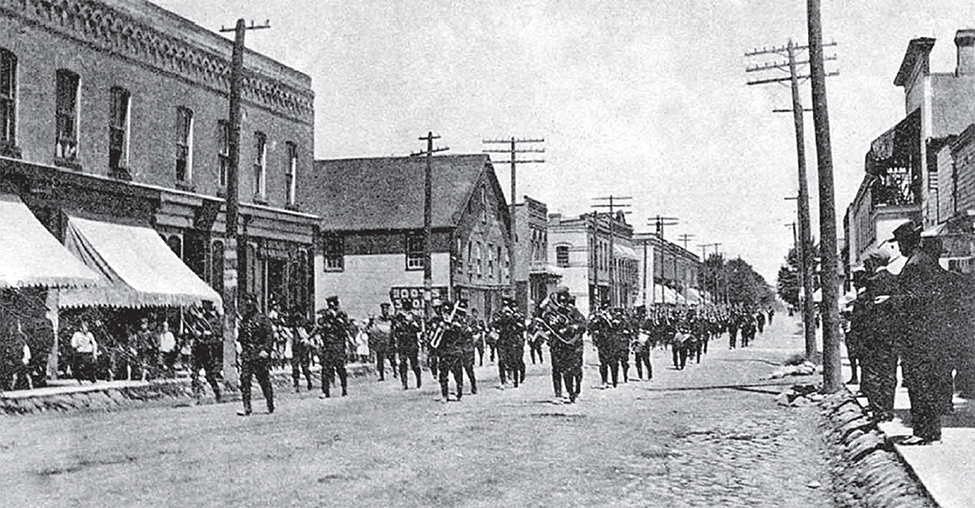

Watford boys return from camp: The troops often were celebrated with parades and spectacular send-offs and returns. Courtesy D Hollingsworth.

There was a sense by many, however, that they needed to lend their support as much and as best as they could. Women's organizations were heavily involved in various ways. Members of the Imperial Order of the Daughters of the Empire (IODE) in Watford were a case in point. On April 6, 1915, Mrs. Newell hosted the monthly meeting at her home with Mrs. Vail assisting in helping with “Tea… served in the dining room and library, the tables looking very dainty and pretty with beautiful cut flowers.” After the opening exercises which included the singing of the “Maple Leaf Forever” the women carried out a program of recitations and provided their compatriots with important news of programs and efforts being made on the part of the war effort, including information on how school children in Toronto saved newspaper clippings “and arranged in a book so that important news items, editorials, etc. might be read by our boys each week and thereby be interested and kept in touch with the outside world”. Mrs. William Thompson received a letter from the secretary of relief work on the Watford chapter's contributions. The letter explained that

we duly received on the 29th of March, the consignment consisting of six bales of clothing, which you were kind enough to forward to our relief work for the victims of the war in Belgium, representing a contribution from the members of your Society. We are very grateful indeed to you for this splendid gift and… kindly thank… all the generous contributors for their… kind interest in the welfare of destitute and distressed Belgians.8

The Women's Institute was also heavily involved in the war effort. Meeting at the Foresters' Hall in on July 8, 1915, it was noted that “The Roll Call was answered by each member making a donation of 2 sheets or some other useful article for the wound[ed] soldiers in the Hospital.” At the end of the meeting “A box of Hospital supplies was packed.” References to the war effort were made at most meetings and it was decided that at their November meeting the women would collect a box of clothing to help beleaguered Belgians. In the meantime “[a] parcel containing 6 pillow slips and eight grey flannel shirts was packed for [the] Red Cross society…” and the meeting closed with the singing of “God Save the King.”

On February 14, 1916, eleven members of the Women's Institute met at the home of Mrs. D. Falloon to make “arrangements… to entertain the Watford Soldiers at a Banquet” two days later. As the minutes recorded,

The Watford Unit of Lambton's 149 marched out to Village and were entertained by the members of the W. I. at the Orange Hall to a dinner. A Programme consisting of Music -- Mrs. Kennedy, Miss L. Ross, Mrs. Beer and Mr. Kennedy. Addresses by Revs Shore & Kennedy & Mr. Young. Song by private E. Mayer.

In total there were forty-two soldiers, thirty gentlemen and ten lady guests as well as eighteen members of the Women's Institute making for a total of 100.9

Having done their best to send off local soldiers, an announcement of the upcoming meeting for March 9, 1916, indicated that “[t]he topic for discussion will be ‘Patriotism.' [and] A bale will be packed for the Red Cross, Toronto.”10

While many women laboured to do what they could from the distant vantage point of , a few were afforded more direct connections to aid in the horrors inflicted by warfare. Margaret Saunders made her way across the ocean to Boulogne, France, where it was noted that she was “working hard to relieve the distress among the civil population.” The Watford Guide-Advocate informed its readership that Saunders represented “the canal boat fund, which is part of the Belgian soldiers' relief fund….” Saunders and her compatriots had “charge of a motor launch which carries supplies along the canals in Belgium.” In addition to these regular forays to bring relief to those who needed it, Saunders was also part of a team looking after 120 Belgian children who had been “left destitute since the war.”11

For those in who had sons or daughters overseas there were always the letters providing them with a precious connection to those in the danger zones. Due to restrictions on the information that could be put down in writing, most letters from the front were deliberately vague. Very few letters described the true horror of life in the trenches, partially due to the orders of the censors and military authorities, but also due in part to self-imposed censorship. Most soldiers came to believe that a true description of their lives at the front and admission of fear or distress would unduly burden loved ones at home.

For the most part these letters were generally upbeat and cheery, at least in the earliest stages of the conflict. Writing in March 1915 to the editor of the Watford Guide-Advocate, Private Glenn W. Nichol is a case in point. The letter is full of bravado and he explained “I am writing this letter sitting on a sand bag in the trench occupied by our platoon (which is the front trench) and the sun is shining brightly, which has a tendency to make one think of spring….” However, he tempered this apparent idyllic description by noting that while “[a]t the present moment everything is quiet and peaceful and one would hardly realize that a great war was in progress… the stillness will soon be broken by the sound of guns and bursting shells.” He also referenced the discomforts that were associated with snow in the trenches. Nichol's thoughts apparently did not stray too far from the town he had left behind, for he explained that “The boys all wish to be remembered to the Watford people and also others of their acquaintance.” Indeed they appear to have reserved a special place in their hearts for one cohort of Watford's population noting that “[t]he boys say they will all marry and settle down after this, so kindly tell a few of the fair sex to remain spinsters until our return.”

Another Watford boy, Lieutenant R. H. Stapleford, having been temporarily removed from active duty due to a bout of acute appendicitis, explained to readers of the Guide-Advocate that “We have a number of officers laid up, wounded and sick, but no deaths. The 27th have had no deaths to date and the boys are second to none in the firing line. Weather in France is getting better.”12

Lloyd Cook in Scotland, c. 1918. Courtesy D Hollingsworth.

The war crept into people's lives in varying degrees. On his family's farm, resident Russell Duncan noted on May 18, 1915 that “Uncle Robert Burgar left Toronto on Friday 14th for the front.” He then noted laconically, “I went to town tonight.”13

For the most part the war was a distant thing. Crops still grew, livestock needed to be fed, meals were made, floors were swept, merchandise was stocked and school was attended. The war was, at least for the first few months, a relatively harmless patriotic adventure.

Things changed dramatically in the spring of 1915. While Stapleford and Nichol had been heartened by the lack of local losses at the front, much of that innocence was soon lost. While the initial reports of casualties explained that some local men were wounded, including two Watford boys, the initial trickle of information soon came fast, furious and unrelenting. Seldom did a week pass by without the picture of a fallen township or village soldier.

On April 22, 1915 two men from the Watford unit, John Ward and Alfred Charles Woodward, were killed. Both men were natives of England and had come to start new lives in the New World, only to die in the trenches of the Old. The following day Village lost of one its own when Sergeant Major Lawrence Gunne Newell was killed in action, a few months short of his 27th birthday, leaving behind his sorrowing parents, Thomas and Sarah. A memorial service was conducted at St. Mary's Anglican Church on May 9, 1915, replete with an honour guard of 50 men of the Home Guard and a throng of other mourners. Killed at the battle of Langemarck, it was noted — though not entirely accurately — that Newell had the dubious honour of being “the first member of the St. Clair Borderers to meet death at the front.” While it was noted that the church was a comparatively large one, “it could not hold one half of the immense crowd that had gathered to pay their last respects…”14

The news continued to be grim when on June 15 both Frederick Bert Wakelin and his brother Tom were killed. Like Ward and Woodward, these two men had come to Canada from homes in England. Their loss was regretted by their friends in Watford and by their parents back in Northamptonshire, England. In the end, of the 25 Watford area men who left Watford station in August 1914, 19 would survive the war and make the return trip.

Ivan Bryce, Russell Duncan. Courtesy H Van den Heuvel.

Lieutenant Stapleford himself would not emerge unscathed from the earliest months of war. Wounded, his injuries proved so serious he was permitted to return home to Canada on a three month furlough.15

One of the important daily activities for farm and townspeople was a visit to the post office, even for those on the newly-instituted rural delivery system. For those living in the north-eastern corner of , a trip to the post office in Arkona was a regular occurrence and provided people with an opportunity to visit with friends and exchange news and local gossip. While their elders discussed the condition of crops, exchanged dress patterns or recipes and retrieved their mail, the children would often play a round of “Pussy in the Corner.” However, one day in late June 1915 seven-year-old Cecile Dunham noted that the normal cheerful hubbub of the post office was utterly absent. As she accompanied her mother in to collect the mail, she noticed small knots of people standing about speaking in shocked whispers. Word had come that Private Roy Fair, aged 21, had been killed at Festubert. The son of Rev. Hugh and Eliza Fair of Arkona's Methodist Church, Roy had the dubious honour of being the first soldier from the Arkona area to die in the conflict.16 In one fell swoop, his death put a human face upon the far-off tragedy that taken one of their own. It also had the effect of altering local viewpoints on what had until then been perhaps complacently viewed as, at best, a great patriotic adventure and, at worst, a terrible ordeal somewhere “over there.”

The loss of so many promising young men certainly took its toll on the countenance of those left behind. By early August there was discussion of a more direct contribution that the people of could make; namely the purchase of a machine gun for the use of Canadian forces overseas. It was widely known that Plympton Township Council was entertaining a similar proposal and one subscriber to the Watford Guide-Advocate urged Council to follow suit. If Council should object to this proposal the writer noted that:

I would suggest that a gun be given by forty men of the township. If a gun is a good substitute for forty men at the battlefront, then let forty men, who are too old or unfit or unable to volunteer, give $20 each. This would make $800 and be sufficient to purchase a machine gun and the first few rounds of ammunition. I would gladly be one of the forty.

The editor of the Guide-Advocate urged that the letter's contents be taken to heart and admonished “Let everyone do his bit.” While it is unclear what the response of Council was, enough local interest was manifest to hold a meeting at the Watford armoury on August 9. The meeting “was not very largely attended, but those who were present were enthusiastic over the matter,” and it was decided that a request should be presented to Lambton County Council as a whole. It was suggested that the county provide a total of twenty-five machine guns from general funds available to them for discretionary use.17

Letter From The Home Front From Capt. Finley Chalk: August 4th, 1917 …. A great many people think that the infantry have all the hard ships in this war, but such is not the case, as a division only remains in action for a few days at a time and is then taken back for a rest well out of all gun fi re, while as regards the artillery, they are [sic] seldom get rest, but when their infantry is resting they are attached to another division and always in a division. The success of the great battle today depends on the careful preparation that is made by the artillery and until the barb wire and machine guns are levelled no artillery can advance. It takes weeks or months to get ready for a great battle and all that time our artillery transports are busy night and day in preparing material and ammunition for the time when the great battle is to take place. They are also under shell fire night and day whether at home or on the roads. No camp is safe as they are all in range of the long distance guns we have to-day…. SOURCE: newspaper clipping (n.d.) from Betty Greening.

The disillusionment that had begun to be apparent even as early as 1915 slowly grew. War weariness had clearly set in by 1917. The steady stream of news of more battles and apparent successes could do little to mask the dreariness and horror that was the face of war. The regular reports of men either killed or wounded dominated the front pages of the newspapers, reminding all who read them of the real cost of the conflict.

As the war dragged on, the number of volunteers began to dry up too. Farmers, pressured to produce more and more, were also becoming antagonistic toward the calls made by political and military leaders to encourage their sons to enlist. Idealistic young men and women, who had viewed the conflict as a noble crusade, began to have second thoughts.

Political battles raged and intensified as the government of Sir Robert Borden fought the 1917 general election on the question of conscription. It was a desperate gamble which Borden knew threatened to tear the country apart, but he also felt honour-bound to the men and women who suffered and died at the front not to break faith by rejecting conscription and not “passing the torch.” The 1917 election was one of the bitterest and most divisive in Canadian history. The war seriously divided the Liberal Party and Anglo- and Francophone Canadians. It also intensified the rural-urban divide in otherwise loyal Anglo- Canada. Many farmers refused to support Borden and his conscription party. Those who did not join Borden's so- called National Coalition voted instead for the remnants of Sir Wilfrid Laurier's Liberal Party.

The war was also coming to be felt more and more in daily life, even in Twp. Coal supplies were increasingly scarce, making life difficult for those who used it as the primary means of heating their homes and cooking their food. People relied on those in the know for tips as to when the next shipments would be arriving at stations in Watford, Thedford and Forest. Farmers would hitch their teams to wagons and make early morning trips to the various depots in hopes of getting a minimum supply of coal before the meagre resources were completely depleted. Various churches and organizations had to make do as well. In Arkona, the Methodist and Baptist Churches pooled their resources and switched between their sanctuaries on a weekly basis to save precious coal reserves.18

In February, 1918, Sergeant-Major Glenn Nichol returned to Watford “quietly and unexpectedly… and in so doing defrauded the citizens of an opportunity of meeting him at the depot and tendering him a fitting public welcome.” It was noted, however, that “ ‘Nic' never did like a fuss and consequently did not give his friends a chance to make one.” Possibly such a homecoming might have been too much an ordeal. Whatever his feelings, he was not to escape the attentions of other Watford residents. Having enlisted in August, 1914, he had served on the Western Front from 1915 onward. At Ypres he was “shot through both legs and afterwards crawled through a trench over a mile to the base hospital….” After recovering he returned to the front and fought “in the battles of Vimy Ridge, Courcellete and other engagements.” He was awarded a medal for his bravery in the field and had been sent home to Canada to help train new recruits.19

One of these new recruits may well have been farmer Russell Duncan. His diary made sporadic mention of the war from 1914 to 1918, but he soon had a direct stake. On April 23, 1918, Duncan went into Watford to see “A Soldier's Comfort” at the Lyceum. He was undoubtedly aware that the war was about to bear down upon him in a big way. With the election of Robert Borden's “National Coalition,” conscription was passed in Parliament. Like many in rural Ontario, it appears that members of the Duncan family were not at all happy about the prospect of sending their sons off to the far-flung conflict. On April 27 Russell Duncan explained that “Father went to Petrolia with Freeman Birchard this afternoon to a mass meeting to send a petition to Ottawa in regard [to] the M.S.A. [Military Service Act] as all between 20–23 have to report [in] May.” For his part Russell and his brother, Walter, “bored and dug post holes around garden…” and then accompanied their sister into Watford. On May 4 Duncan recorded that having disked the corn, he accompanied his brother into Watford. Waiting for them there they found “registered letters to appear in London on 17th of May for duty.” Work did not let up as the date for reporting drew nearer, although Russell did manage to slip down to Sarnia to see some relatives. On a cool May 16, Russell and his brother Walter “went down to London on the 11 train today and had dinner at Broadleys. We had our photos taken and went to Springbank [Park]….” Having called on another friend they stayed the night at Broadleys. The following day — May 17, 1918 — with his thoughts not straying far from home Russell wrote:

Fine and warm. Father and Mother went down and clipped the sheep and planted some potatoes. Walter and I reported for duty at 8:30 [and] were examined and taken down to Queens Park for dinner. We had to stay there… till 3 PM to get our leave off. We both got Class A 2, 15 days leave. We took the 8:39 train home tonight. C. Comp. No. 3135757.

Walter Duncan. Courtesy H Van den Heuvel.

Russell Duncan kept up his diary until the end of May, followed by his mother, Violet (Burgar) Duncan, who kept up the diary and recorded that on May 31 “Russell and Walter had to go to London today to be soldiers. Alma and Edna Williams and Aunt Rean were here for dinner. There was a lot of us up to the station to see the boys away. It was very warm.” Mrs. Duncan recorded that photos of her two sons arrived and she then noted ruefully on June 3 that “Two years ago since Robert was killed.” Some of the emotion of a mother with two sons away to war is captured in a poignant passage Violet Duncan penned on June 11, 1918. She explained that despite a houseful of company for tea, later “I filled the straw tick [and] was trying to clean up stairs but got so lonely I had to come down. I wed [weeded] out some of the black seed onions and set out some blue berry plants.” Her subsequent entries detailed life on the farm, but made frequent mention of her two sons or others who had gone off to war. When she could, she packed home baking and food to send with those who might see her sons at camp, and on June 14 she went to London herself to see them.20

The war dragged on and on. An attempt by German forces to smash through the western front and slice toward Paris caused a major panic amongst the allies. The Germans were ultimately pushed back. There was much speculation that the war would continue for another gruelling and weary year, and little indication that the immediate future would hold anything different. Letters still came from the front and the papers reported on war news, in addition to reports on the comings and goings of the local population. There was consternation and some fear about the Russian Revolution of October, 1917. Bolshevism had reared its ugly head and shocking pieces appeared, warning the people of about “Bolsheviki ‘Free Love' Plan.”21

In October, 1918, there was a great deal of joyous commotion when word came that the war had ended at long last. On their farm south of Arkona, the Dunham family were startled by the sounds of steam whistles and the peeling of church bells, and upon inquiring they were informed the war was finished. It was, however, a mistake; the conflict would rage for another month.

The end of the war came rather unexpectedly. Austria- Hungary had largely disintegrated by the end of 1918 and was a mere shadow when it more-or-less ceased to exist and withdrew from the war. A revolution swept Germany and the Kaiser was forced into exile. A few days later German and Allied officials agreed to end the fighting with an armistice on November 11, 1918, at 11:00 a.m. At that time the guns went silent for the first time in over four years. The news spread like lightning around the world. On her farm in , Violet Duncan wrote:

The morning [London] Advertiser's first words was [sic] “With you I rejoice. Thank God for the victories which the Allied armies have won and have brought hostilities to an end.” King George. It was a fine day. Dan & Walter & Russell drew gravle [sic] for our drive shed. Dan went up town in afternoon it was a holiday in town in afternoon and evening to celebrate the war and Dan and Russell went up in evening. They had a great time. I washed & Mildred churned.22

Meanwhile, in the northern part of the township, the family of Nicholas and Amelia Sitter were labouring away, loading the harvest of turnips into storage in the barn. Eleven-year-old Edgar helped his father and eldest brother dump the turnips from the wagon into the barn cellar, while five year old Corena and the youngest brother, Leonard, worked to push the dumped loads to the back wall and ensure that the turnips were evenly distributed. As the family worked, the day's quiet was shattered by the din of tolling bells and the piercing shouts of steam whistles coming from the direction of Arkona. The family hardly knew what to make of the noise, but soon word came that the war was finally over.23

Thousands swarmed into Watford upon hearing the news and the Guide-Advocate recorded that:

A happier throng never gathered together within the limits of our loyal little town than assembled on Monday afternoon and evening. The news of the signing of the armistice by Germany had been looked forward to for some days and, when the glad tidings were officially announced on Monday morning, the enthusiasm of the citizens was unrestrained. In a very short time flags were flying from almost every building in town and arrangements were being made for a celebration later on in the day. Reeve Fitzgerald at once issued a proclamation for a public half-holiday.

An impromptu service was held at the Watford bandstand with prayers of “thankfulness and gratitude to God that the world had been set free and the religion of hatred and brutality banished forever.” Following the service, a parade set out along the main thoroughfares with some “fifty elaborately decorated autos.” The paper explained too that:

A feature of the parade was the Fenian Raid Veterans, whose conveyance — a hay rack — looked somewhat grotesque among a lot of expensive motor cars. As there were no buzz wagons in the sixties the veterans, however, felt quite at home in their vehicle. Another feature was one representing a German soldier surrendering, with his hands upraised in ‘Kamerad' style.

After the festivities briefly broke for supper, the celebrations continued into the night with a torchlight procession and a “monster bonfire on the government lot west of the armoury. This thirty-foot construction was topped by an effigy of the Kaiser, the booming of anvils, the illumination of fireworks and the noise of the jubilation made the scene one never to be forgotten.” Watford musicians were complemented by members of the Kerwood band. While much of the celebration appears to have been dominated by village males, it was noted that “The ladies joined in the enthusiasm and added to the success of the celebration, which was kept up until a late hour."24

While the automobile had played a central role in the celebrations in Watford, it wreaked havoc with similar commemorations in Arkona. It was explained that:

Arkona celebrated the close of the war both in London and in Arkona. Almost every car in and around this place took its load to the Forest City on Monday, so that plans laid for a local celebration were completely upset. But Tuesday evening Arkona citizens in a well attended Union Thanksgiving Service at the Methodist church celebrated in good form. Revs. J. Ball, G. B. Ratcliffe and C. W. King and Messrs. A. A. Barnes and Thos. Lampman in brief addresses presented the outstanding war and peace conditions as reasons for thanksgiving.

A few days before, the people of the village had celebrated the heroism of returned soldier Corporal Beaumont F. Flack who had been “wounded in the thigh and is still suffering from German gas….” Unable to stand while addressing the gathered audience, he reported on his experiences and noted, to the collective favour of the assembled, that “Canadians were regarded as regular terrors by the Huns when it came to the bayonet action….”25

The jubilation masked a great deal of utter relief that the conflict, the “War to End All Wars,” was at last over. The spontaneity of the November celebrations gave way to the realities of a Canadian winter. However, planners and organizers were bent on celebrating in a more formal way the cessation of the hostilities and across Canada plans were put into effect to celebrate “Peace Day,” when the formal treaties being formalized in Paris were finalized and signed. King George V proclaimed July 19, 1919, to be “Peace Day” and the local people gathered to commemorate and celebrate. There was less of the spontaneous joy that had infused the demonstrations on November 11, but nonetheless many turned out to remember. As the Watford Guide-Advocate reported:

Peace Day was quietly and reverently observed in Watford. There was no spontaneous outburst or surface excitement. The spirit of the day was tinged by memories of the men for whom there was no home coming, while the citizens quietly did honor to the men who had made a Peace Day possible. The proceedings were tempered with dignity, thoughtful people showing their thankfulness for the goodness of God and the achievements of the Allies by attending the service held in Armory. About 9:30 the children assembled at the public school and under the supervision of Principal Shrapnell paraded the principle streets. Some exceedingly pretty and appropriate patriotic costumes and numerous flags were in evidence, but the absence of music of any kind made the procession a very quiet affair, and on that account it passed along without being seen by many people. The march ended at the Armory, most of the children remaining there for the religious service. This was carried out according to the published program, the only exception being the absence of Rev. A. A. Barnes.

A baseball game between Watford and a visiting London team ended with a 7-6 victory for Watford and there were fireworks displays in the evening. It was reported simply that “[m]any of the farmers attended the Peace Celebrations in London and Sarnia….”26

The reverence and quietude that marked the Peace Day celebrations did not, apparently, give proper vent to much of the pent-up feelings the end of the war had caused. As a result Watford planned to welcome home area soldiers with a huge day of celebration, replete with a parade with lots of music and fanfare. The day included the often-controversial Sir Sam Hughes, Minister of Militia and Defence (1911-1916), who spoke alongside other dignitaries, and apparently “received an enthusiastic ovation.” The returning soldiers and three nursing sisters — R.F. Reed, Clara Tye, and Diana Dodds — were heralded.27

List of Watford Veterans World War I, 1914-1918.

| BATTALIONS |

|

1st. 27 Regiment R.W. Bailey Bury C. Binks M. Blondel W. Blunt M. Cunningham B. Hardy A.L. Johnston R.A. Johnston C. Manning G. Mathews FCN Newell, DCM L. Gunne Newell W. Glenn Nichols Arthur Owens F. Phelps H.F. Small E.W. Smith R.H. Stapleford Thom. L. Swift C. Toop F. Wakelin, DCM T. Wakelin C. Ward J. Ward T. Ward Sid Welsh H. Whitsill Alf Woodward 18th Regiment Wm. Autterson C.A. Barnes C. Blunt F. Burns J. Burns Geo. Ferris G. Shanks S.F. Shanks Edmund Watson Walter Woolvett 28th Regiment Thomas Lamb 33rd Regiment Geo. Fountain Lloyd Howden Percy Mitchell Gordon Patterson 34th Regiment E.C. Crohn Macklin Hagel Henry Holmes C. Jamieson Leonard Lees Wm. Manning S. Newell Stanley Rogers 70th Regiment A. Banks Sid Brown Vern Brown Art Bullough Alfred Emmerson Ernest Lawrence C.H. Loveday Thos. Meyers Jas. Wardman S.R. Whalton 98th Regiment Roy Acton 116th Regiment Clayton O. Fuller 135th Regiment Nichol McLachlin 142nd Regiment Austin Potter Lt. Gerald I. Taylor 149th Regiment Fred Adams J.C. Anderson A. Armond C. Atchison L.H. Aylesworth W.C. Aylesworth D. Bennett B.C. Calley R. Clark F. Collins F.E. Connelly E. Cooper H. Cooper M.W. Davies A. Dempsey E.A. Dodds S.E. Dodds Eston Fowler J.R. Garrett Geo. Gibbs S. Graham C. Haskett S.H. Hawkins H.B. Hubbard H. Jamieson Wm. Kent John Lamb W.D. Lamb C.F. Lang Charles Lawrence R.J. Lawrence A.H. Lewis E. Mayes J. Menzies H. Murphy J. McClung S.L. McClung C. McCornick H.I. McTeley Pte. McGarity W.C. McKinnon Lot Nichols Edgar Oke W. Palmer G.A Parker W.C. Pearce C.F. Roche F.J. Russell Bert Saunders W.J. Saunders W.J. Sayer E.A. Shawnessy C.E. Sisson C. Skillen A.I. Small W.H. Smyth A.W. Stilwell T.E. Stilwell R.D. Swift F. Thomas H. Thomas B. Trenouth Richard Watson Alex White F. Whitman Frank Wiley A.C. Williams W.A Williams Pte. Wilson G. Young W. Zavitz 196th Regiment R.R. Annett Service Corps R.H. Acton Frank Elliott Art McKercher Henry Thorpe 2nd division Calvary Lorne Lucas Chas. Potter Frank Yecks Mounted Rifles Fred A. Taylor Pioneers W.F. Goodman Wm. MacNally Engineers Cecil McNaughton Basil Saunders J. Tomlin Army Medical T.A. Brandon MD Allen W. Edwards Basil Gault Capt. R.M. Janes Wm. McAusland Norman McKenzie W.J. McKenzie MD Jerrold Snell Gunner Russ G. Clark RNC VR John T. Brown T.A. Gilliland First Petty Officer Fred H. Haskett Dental Corps Elgen D. Hicks Capt. L.V. Janes H.D. Taylor PPCLI Gerald H. Brown Central Ontario Regiment Verne Johnston Basil Ramsay Ches Schlemmer Royal Canadian Air Force D.V. Auld Lt. Leonard Crone J.C. Hill Lt. M.R. James E.C. Janes Lt. J.B. Tiffin American Army Bence Coristine Fred T. Eastman Stanley Higgins Special Reserve Nelson Hood Western Ontario Regiment 1st Depot Fred Birch Herman Cameron Lloyd Cook Alvin Copeland John F. Creasy Leo Dodds Tom Dodds Wellington Higgins Fred Just Reginald J. Leach Bert Lucas Geo. Moore Mel McCormick Russ McCormick Leon R. Palmer James Phair John Stapleford J.R. Williamson |

| BATTERIES |

|

3rd Alfred Leyi 29th John Howard Wm. Mitchell 63rd Clare Fuller Ed Gibbs George W. Parker Walter Restorick 64th Romo Auld C.F. Luckham Harold Robinson 67th Edgar Prentes 69th Chester W. Cook. |

One Watford youngster, four year old Alec McLaren — son of the local pharmacist — recalled

I was in the back seat of a touring car with my Mother & Father; they were not driving; there was another couple in the front who owned the car. There was a big celebration in Watford… There was a big parade, bands, noisemakers, streamers & everything. One of the things I recall is at the time a flag pole at the side of the armoury building, an old four legged wind mill type and on that flag pole they had erected a stuffed effigy of the German Kaiser and as part of the ceremony, along with all the noise makers, streamers and everything they burned the Kaiser.28

Burning the Kaiser, November 11, 1918. Courtesy Watford Historical Society.

Even as the war came to its conclusion, however, there was another menace appearing on the horizon with more apparent implications for the people of . The scourge of the dreaded “Spanish Influenza” came increasingly to the attention of the populace. This led to an explosion of warnings about the growing pandemic. Advertisements, masquerading as news pieces, both attempted to inflame and calm fears by selling concoctions to ward off the disease including “‘FRUIT-A-TIVES' The Wonderful Fruit Medicine — Gives the Power to Resist This Disease.”29

While the population of was still coming off the headiness of the armistice, word came about the real implications of the looming threat of influenza. Word reached the township that Meryl Logan of Massena, New York, but formerly of Forest, had succumbed to the dreaded flu. The Watford Guide-Advocate explained that “The Spanish Influenza Epidemic was at its height in [Massena].” The reality was that and Canada as a whole were to face a rapidly spreading pandemic that would kill at least as many Canadians as the 60,000 lost in the Great War.30 Before the outbreak was over, many families in , Watford and surrounding area would be sorely afflicted.

Normally those most at risk to the worst effects of influenza were the elderly and the very young. The outbreak of 1918 and 1919, however, had the worst effects on those who were otherwise in their prime. Disproportionate numbers of men and women in their twenties, thirties and forties succumbed to the dreaded influenza.

Few knew how to cope with the disease, and as it advanced schools were closed and public meetings suspended as people attempted to protect themselves and their families. Physicians did what they could to help their patients. Some doctors prescribed plenty of fresh air as a way of helping the afflicted, but given that the “'flu” was most potent during the fall and winter this often wore down defences. It may not be surprising that pneumonia often resulted. In Arkona Dr. Huffman ordered that his patients be kept warm and well-hydrated. It was later said, anecdotally, that he lost fewer patients than many of his colleagues.

The losses were devastating. On November 2, 1918, 74-year-old Matilda Sullivan died on Lot 9, Con. 4 NER, after battling the 'flu for four days and developing pneumonia. Two days after the widowed Mrs. Sullivan's death, Bert Edmund Fulcher of Watford died, a week after becoming ill. He was less than a month from his 31st birthday. Watford blacksmith James Willoughby died on December 20, after fighting for his life for one and a half weeks. On January 19, 1919, 42-year-old Edward Pearce died in Watford, eleven days after first exhibiting symptoms. While precise numbers are lacking, it becomes clear that before the pandemic had spent itself, dozens of local people had succumbed, and shattered families, some of whom had already coped with losses from the war, were left to pick up the pieces and move into an uncertain peace.31

Endnotes

These links were used at the time of publishing in 2008. Some links may have changed or may no longer be active.

1. Watford Guide-Advocate, July 24, 1914, and July 31, 1914.

Lorena (McChesney) Dunham, letter of March 10, 1914, Arkona, Ontario, to Tom and Maria Brett, Drayton, Ontario. T. M. Russell Dunham collection.

2. Stephen T. Morris, diary entries for August, September, and October 1914.

3. Russell E. Duncan, diary entries for June and August 1914. The Duncan and Morris families were well acquainted with one another. On April 3, 1918, Russell Duncan wrote that “Bert, Orville, Mildred, Walter Aunt Rene, Estella and I walked down to Steve Morris's tonight [for] George's birthday he is 16 years old.”

4. Watford Guide-Advocate, August 7, 1914. It was also explained that “Carl Goodhand, a pupil of the Birnam school, who passed the entrance examination, is deserving of the congratulations he has received, having worked and written under most trying circumstances. Last winter he had the misfortune to have his right hand cut off in the cutting-box and just before Easter he started to school after an absence of three years and a half, attending in all a period of only fifty-three days when he wrote the exam.”

5. Watford Guide-Advocate, August 21, 1914.

6. Greg Stott, “Arkona Residents Remember,” Watford Guide-Advocate, November 4, 1998.

Florence (Austin) Hill, interview by Greg Stott, June 2, 1996.

7. Watford Guide-Advocate, August 21, 1914.

8. Watford Guide-Advocate, April 16, 1915.

9. Women's Institute, Minute Book, June 10, 1915–February 16, 1916.

10. Watford Guide-Advocate, March 3, 1916.

11. Watford Guide-Advocate, August 6, 1915. Margaret Saunders' efforts did not go unrecognized. She was presented to Princess Clementine, a cousin of King Albert of the Belgians.

12. Watford Guide-Advocate, April 9, 1915.

13. Russell E. Duncan, diary entry, May 18, 1915.

14. Watford Guide-Advocate, May 14, 1915.

15. Watford Guide-Advocate, August 13, 1915.

16. Greg Stott, Sowing the Good Seed: The Story of Arkona United Church, G. Stott Publishing, 1996, p. 43.

Cecil (Dunham) Harrison, interview by Greg Stott, May 19, 1996.

Watford Guide-Advocate, July 2, 1915, and July 9,

17. Watford Guide-Advocate, August 6, 1915, and August 13, 1915.

18. Russell Dunham, October 1997.

19. Watford Guide-Advocate, March 1, 1918.

20. Russell Duncan, diary, entries for April, May, and June 1918.

21. Watford Guide-Advocate, November 8, 1918.

22. Russell Duncan, diary. Entry penned by Violet (Burgar) Duncan, November 11, 1918, who kept up his diary after he enlisted.

23. Greg Stott, “Arkona Residents Remember,” Watford Guide-Advocate, November 4, 1998.

Edgar and Corena Sitter, interviewed by Greg Stott, November 1992.

24. Watford Guide-Advocate, November 15, 1918.

25. Watford Guide-Advocate, November 15, 1918.

26. Watford Guide-Advocate, July 25, 1919.

27. Watford Guide-Advocate, August 29, 1919.

28. Alec McLaren, video interview of May 2006, by Paul Janes. Transcribed by Janet Firman.

29. Watford Guide-Advocate, November 8, 1918.

30. Watford Guide-Advocate, November 22, 1918.

31. Janice Dickin, “Influenza,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, 2000, p. 1164.

Ontario Vital Records, various examples from Watford and , 1918–1919

Greg Stott, I Think I Have the Dunham Pedigree: The Story of the Robert and Louisa (Green) Dunham Family, G. Stott Publishing, 2006, pp. 265, 394–395.

Subscribe to this page

Subscribe to this page