From Slate to Laptop (Education)

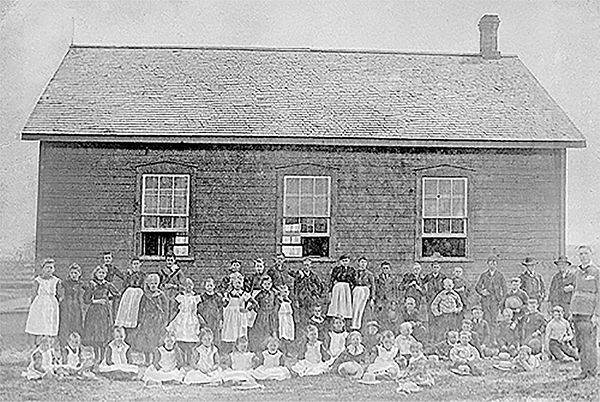

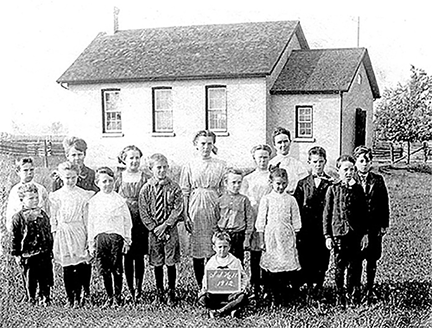

Kelvin Grove School: A typical early 20th century school.

by Dr. Greg Stott

The early settlement of Township by people of European background during the 1830s and 1840s occurred during a period of social ferment. This turbulence played out in the political contests that erupted in outright rebellion, but also in the classrooms across the colony of Upper Canada that shortly became part of the United Province of Canada.1

By the early 1840s Governor-General Sydenham had surveyed the state of education in Canada West and determined that its reformation would be one of his top priorities. Indeed he thought the existing systems for both Upper and Lower Canada were in a deplorable state and quite frankly an embarrassment for fairly developed societies. His attempts to create a unified school system across both halves of the United Province failed, due to the antagonistic politics that tended to pit west versus east, anglophone versus francophone, and perhaps more importantly, Protestant versus Catholic. Even within Canada West there was infighting. Bishop John Strachan wanted Church of England students to be able to have schools separate from those of Presbyterian and Methodist background to counter undue American influence.

A series of acts were passed and then repealed, until in 1844 Wesleyan Methodist minister Egerton Ryerson, a noted reformer and education advocate, was appointed as the Assistant Superintendent for Canada West. Two years later he was elevated to the position of Superintendent. In 1846 he put forward a series of recommendations that led to the Common School Act of 1846. This was an important development and would lay the groundwork for all subsequent acts that culminated in 1871 with legislation that provided for universal and compulsory education for all children.2

While the Department of Education would control issues surrounding curriculum and the training of teachers and so forth, local control in education was still a central plank in the new school system, with a county-level Board of Public Instruction composed of the local common school superintendents and grammar school trustees. There was also a county-based Board of School Trustees which was composed of the local school trustees for each individual school. Three trustees would be elected by the local ratepayers. Each School Section (SS) was thereby effectively run by a separate School Board, although each of these small boards was part of the larger county-based structure and would be under the supervision of these county-based bodies. School inspectors would make regular visits and ensure teachers were up to standards, that the building was maintained, that children were learning and that books were up-to-date.

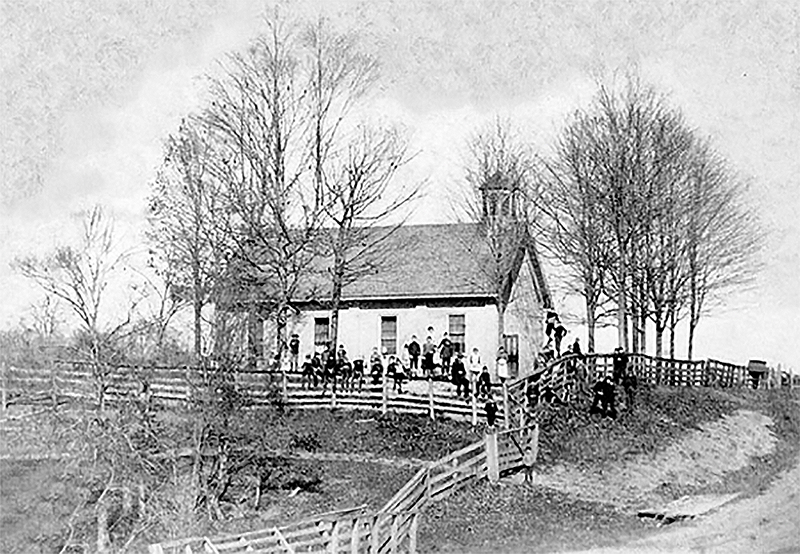

Believed to be the oldest school, Village School was locagted on Lots 1-5 East Guy Street, Plan 2 , just west of St. Mary’s Anglican Church. Courtesy G Herbert family.

We know little about the earliest forms of formalized education in . Presumably most children of the earliest European settlers received varying levels of education from their parents or more learned neighbours. Wintertime may have afforded more time to be devoted to educating the young in terms of reading and writing. Farm labour during the summer may have precluded much in the way of instruction. Inevitably there would probably have been a wide variation in the level and quality of instruction.

Captain Harry and his wife Frances (Sinclair) Alison appear to have schooled their children at home in the vicinity of what would become Wisbeach. While most of their children had been schooled back in England prior to emigration, there is a strong suggestion that the Alison cabin, replete with piano, guitar and harp, and Mrs. Alison’s watercolours and oils, was an educational haven for her children and Alison family associates.3

Even after the establishment of schools, it appears not every family chose to send their children to these institutions. The Laws family arrived in from Scotland in 1858 and as daughter Ellen recalled, “Father taught us all we know. We never went to school, you know. He taught the boys Latin and I learned a little too… but I’ve forgotten it now.”4

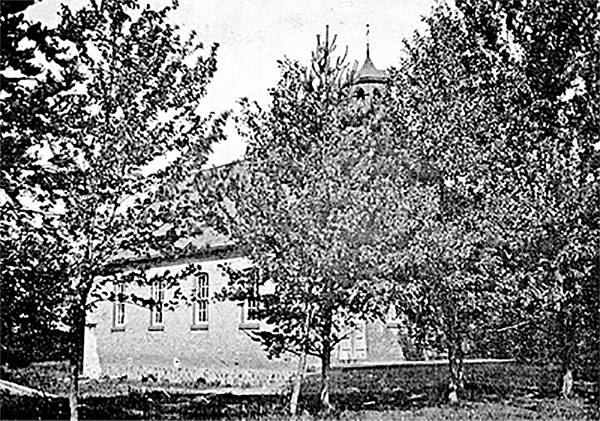

SS#1: In 1850 this school may not have been organized. Courtesy P Evans.

EARLY SCHOOLS

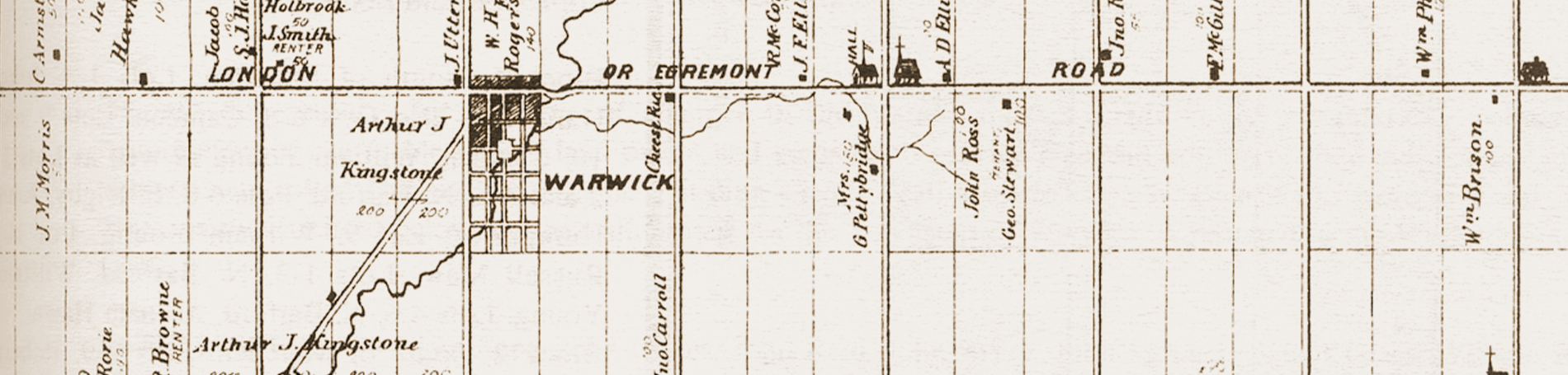

At times it is difficult to correlate traditional histories of the early township schools with surviving contemporary documentation. Tradition has long held that with the emergence of a sizeable service centre at Village by the 1840s, the township’s first school was organized there. The school was built on part of Lots 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 within the village, on land that bordered the recently- established St. Mary’s Anglican Church. The building was erected in 1840 and Joseph Tanner was appointed the first teacher, while Frank Kenward apparently taught somewhat later.5 Earlier schools located on the Egremont Rd. may have been built or established some time in the 1830s,but contemporary evidence for these schools is lacking. While the Village school predated the major educational reforms of the mid-1840s and persisted into the last quarter of the nineteenth century, for reasons that have never been properly explained, it appears never to have been counted or transformed into a school section and therefore never given the title of SS#1. That dignity apparently went instead to a log school built on Lot 7, Con. 3 NER, which was opened in 1850.6

SS#5, c. 1909 Standing: Hope Taylor, ?, ?, ?, Gertie Campbell (teacher), ?, Marjorie Jean Hall, Janet Hall, Milton Hall, George Hall. Kneeling: ?, ?, Lloyd Hall, Carman Scott Hall, ?. Courtesy L Hall.

Contemporary school records paint quite a different picture of the face of education in the 1840s. Records submitted to provincial authorities at the end of 1850 indicate that there were ten school sections organized in and that several of them were of relatively long standing. A report on the status of schools as of December 31, 1850, indicated that SS#1 had “no school in operation [in] 1850 & no report received.”7 However, it was noted that in 1849 the school had reported a total of 36 children between the ages of five and fifteen living within its boundaries. Only one other school section failed to be reported with the schools and that was SS#9, which was a union school with SS#1 at Bosanquet Corners (later Arkona) and as a result was probably reported under Bosanquet Twp. The oldest school was SS#5 which was originally built on the north-east corner of Lot 25, Con. 2 NER. According to records for 1850, the log school building, possibly measuring 16 by 24 feet, had been constructed in 1840, a full three or four years before the Village School. However, 1850 had not been a good year for the school section, for the building apparently burned during the course of the year, presumably in either March or April, as it had only been in operation for two and half months that year. The community had apparently rallied around their school, for while it was not back in session by the end of 1850, it was noted that it had been “repaired by voluntary labour.” The unnamed male teacher was an adherent of the Church of England, but had not been trained at the Toronto Normal School. The 16-by-20-foot log structure for SS#3 appears to have been the second oldest school building, dating back to 1842, while both SS#7 and SS#13 were built in 1843. Four of the schools were only built in 1850, although it is possible that SS#4 (Birnam or Bethel school) and SS#8 had both been organized before SS#10 and SS#11 and SS#12, the latter of which were both called “A new school.”8 (see chart below)

| School Section | Teacher's Religion (All teachers in 1850 were male) | Attended Normal School | Annual Salary | School Building Built: Freehold or Leased | School Dimensions (in feet) | Months Kept Open by Qualified Teacher | Number of Pupils on Roll |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | "No Report" | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| #2 | R.C. | No | £32 10s Without Board | Not Reported: Freehold | 24x20 | 12 | 64 + 6 indigents or nonpaying |

| #3 | Meth. | No | £37 10s Without Board | 1842: Freehold | 16x20 | 12 | 31 |

| #4 | Not Given | No | £30 Without Board | 1850: Leased | 20x20 | 6 | 45 |

| #5 | C. of E. | No | Not Reported | 1840: Freehold | 16x24 | 2 1/2 | 32 |

| #6 | Presby. | No | £35 With Board | Not Reported: Freehold | 20x22 | 7 | 45 |

| #7 | Presby. | No | £30 With Board | 1843: Freehold | 18x20 | 7 | 20 |

| #8 | Meth. | No | £30 With Board | 1850: Leased | 20x22 | 11 | 55 |

| #9 | Not Reported with Warwick: A Union School with SS#1 Bosanquet | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| #10 | C. of E. | No | £24 With Board | 1850: Not Reported | Not Reported | 6 | 17 |

| #11 &12 | Meth. | No | £40 10s Without Board | 1850: Not Reported | Not Reported | 9 | 56 |

| #13 | Meth. | No | £35 10s | 1843 | 18x18 | 9 | 18 |

Source: Archives of Ontario, “Annual Reports of Local Superintendents and Local Boards of Trustees, 1850–1870,”

(Warwick Township), MS 3547, RG 2-17.

SS#3, Elarton 1935 Back row: Billie Jones, Mervin Laird, Jim Jones, Helen Morgan, Jean Morgan, Mildred Clark, Miss Leach (teacher) Front row: Bobbie Morgan, Donald Beacom, Bobbie Beacom, Marjorie Blain, Leslie Skillen, Bert Andrews. Courtesy E Jones.

In March 1852, a frustrated official reported back to his superiors in Toronto about the difficulties he had in dealing with the local school officials in as a whole. As he explained:

It is very difficult in this part of the country to obtain any thing like correct Reports either from Teachers or Trustees notwithstanding the plain Headings & Instructions given in the blank forms yet very few of them are able to fill them or they will not put themselves to the trouble. I have returned a number with explanations & yet cannot get them complete. For instance notwithstanding the plain directions in the Report several Teachers returned in answer to the question “Religious Faith” “Protestant”…. If the Local Supt. had not the power of withholding the last amounts of money, in some cases we would get no report at all.9

While there was clearly frustration created by the apparent apathy of teachers and trustees in terms of filling out government-mandated forms, the Rev. I. Smythe, the incumbent vicar of St. Mary’s Parish, was at least confident in asserting that “I am glad to say that the people generally take an interest in Education….” He qualified his remarks, however, condemning “incompetent teachers and inefficient and obstinate trustees…” and noting that “the progress of the Common School system has been retarded in several school sections.” He was no doubt pleased to report that “in a few instances however where the Teachers have been competent and the Trustees disposed to do their duty the result has been most satisfactory from which I conclude that the Common School system when properly carried out is well calculated to promote the education of the masses and secure general approbation.”10 There was other good news to report in terms of the physical school environment as well as in terms of attempting to reach and educate the general population regardless of age. Smythe was happy to explain that

Union School SS#7 Warwick & SS#2 Brooke: Union schools existed along the south and north boundaries of . Back row: Alfred Acton, Victor Acton, John Acton, Johnny Higgins or Alton McNeil, Roy Wooley, Purcell Blain, Miss Ruth Higgins (teacher). Middle row: ?, maybe Willie Dempsey, Russell Acton, Roy Acton. Front row: ? Leacock, Alice Leacock, Violet Sharp or Beulah Brooks, Alma Mae Acton, Gertrude Kelly, Florence Kelly, Rita Margaret Acton, Ella McNeil with sister in carriage. Courtesy L Acton.

Two new Frame school houses have been erected in the past year and I have been informed that it is contemplated to build several […] during this year so that I hope in a short time the log houses — many of which are very unsanitary — will all have given place to commodious buildings.The Township Library has I think conferred a great benefit on the people by creating a desire for learning and diffuses general information. It contains 500 volumes most of which have been read in the past year. It has been found impossible to carry out strictly the registrations and many of the books being bound in an inferior manner have been much inquired.11

By 1856 there were fourteen schools operating in the township, including the united school sections 11 and 12. While there had been no women engaged as teachers back in 1850, six years later three women, Ellen Barnes, Janet Campbell, and Martha A. Cook, taught at sections 8, 10, and 14 respectively.12 Of the fourteen teachers in the township only William Stewart at SS#15 held a First Class Teaching Certificate. The rest held either Second or Third Class certificates.13 Alexander Fraser, a native of Scotland, is reputed to have been inspired by the situation of SS#2 in a glen and rill and named it Kelvin Grove after his former home Kelvin Side. Fraser was responsible for planting maple trees on the school grounds that were still at the site as late as 1967.14

Union School SS#7 Warwick & SS#2 Brooke: Built circa 1905, this school marked a distinctive change in architecture from the traditional. Courtesy WI Tweedsmuir Books.

Beginning in about 1850, a man by the name of George Brown established himself along the proposed route of the Great Western Railway, taking up quarters in a shanty that had been used by railway contractors. A settlement, initially called Brown’s Corners, gradually grew and a school was established in about 1855 in the northern end of the growing community near the Presbyterian Church and burial ground. William Bryce was apparently the first teacher, followed by John Bodaly, although neither of these men’s names appear in early lists of Twp. teachers. While the school section boundaries were continually being redrawn throughout the middle decades of the century, it has proven difficult to determine if the community, increasingly called Watford, was counted as one of the school sections. Whatever its status within the larger framework, the Watford school had 112 students by 1869, which necessitated the construction of a new two-storey building that sat on Ontario St. The building ultimately burned in 1893 and was subsequently replaced by a two-storey brick building on the old school site.15

| School Section | Teacher and Religion | Teaching Certificate |

|---|---|---|

| SS#1 | John McDonald – R.C. | Third |

| SS#2 | Alex Fraser – Presby. | Second |

| SS#3 | John McDougall – R.C. | Second |

| SS#4 | William Monkhouse – Cong. | Second |

| SS#5 | David Smith – Meth. | Third |

| SS#6 | John Tulloch – Presby. | Third |

| SS#7 | James H. Page – Presby. ? | Second |

| SS#8 | Ellen Barnes – Cong. | Second |

| SS#9 | Adolphus Blush – Men. | [None Listed] |

| SS#10 | Janet Campbell– Presby. | Second |

| SS#11 and 12 | D.M. Hick – Free Thinker | Third |

| SS#13 | William Waller – [Blank] | [None Listed] |

| SS#14 | Martha A. Cook – C. of E. | Third |

| SS#15 | William Stewart– Presby. | First |

Source: Archives of Ontario, Annual Reports of Local Superintendents and Local Boards of Trustees, 1850-1870,” (Warwick Township), MS 3547, RG 2-17, report for 1856.

There are a few surviving anecdotes about schools during the 1840s and 1850s. The earliest teacher at SS#10 at the junction of the Arkona and Egremont Rd. was Harry Ledger, who was reputed to be a veteran of the Napoleonic Wars. Another of the teachers at SS#10 was entrepreneur and arch-Orangeman Robert McBride (1811–1895) who later wrote three books of poetry and explained that he was a “Poet Writing Poems & Songs on all the Evil & Good transpiring in Canada.”16 The much beloved “Uncle” Joe Little taught school on the corner of 9 Sideroad and Con. 2/3 SER for a time.17

Photo Gallery: Warwick Ch 6 will appear here on the public site.

One former student of SS#11 recalled “the dense woods and, how, sometimes at noon hour, they would chance upon an Indian encampment nearby.”18 Agnes (Brandon) Karr’s family arrived in in 1850 and settled not far from the future site of Forest. Decades later she explained that

Well, old Mr. Melon was our teacher. He didn’t have any teacher’s certificate but he taught us just the same. We had to go across the fields and through the woods a mile and a half to the school, and there were two creeks between. In the winter, when the snow was deep, it was a fright. We’d get in the snow banks up to our waists. I often think if it hadn’t been for the good red flannel we wore we would have died. However, I guess we were tough.19

While the education of the youth near Forest was served by an untrained teacher a similar situation existed in the vicinity of Birnam. Jane (Thomas) Luckham (1839–1929) indicated that Rev. Robert Hay taught school to neighbourhood children. Continuing she noted that

…in those days, you know, you didn’t have to have a teacher’s diploma to teach. He was a well educated man and he could teach reading and writing and arithmetic as well as we needed to know them. We didn’t have so many books as you have today, but I think we usually remembered more of what we read.20

Even those students who attended one of ’s early one-room schools, with a qualified teacher or not, did not necessarily remain long. Timothy Gavigan’s father became ill and, as no physician was to be had near, he succumbed to his illness, leaving his widow with a bush farm to clear and run and young children to raise. Her son explained that he never attended a day of school after the age of nine as “[t]here was too much to do to help keep the others. Father was gone and we boys had to get the place cleared.”21

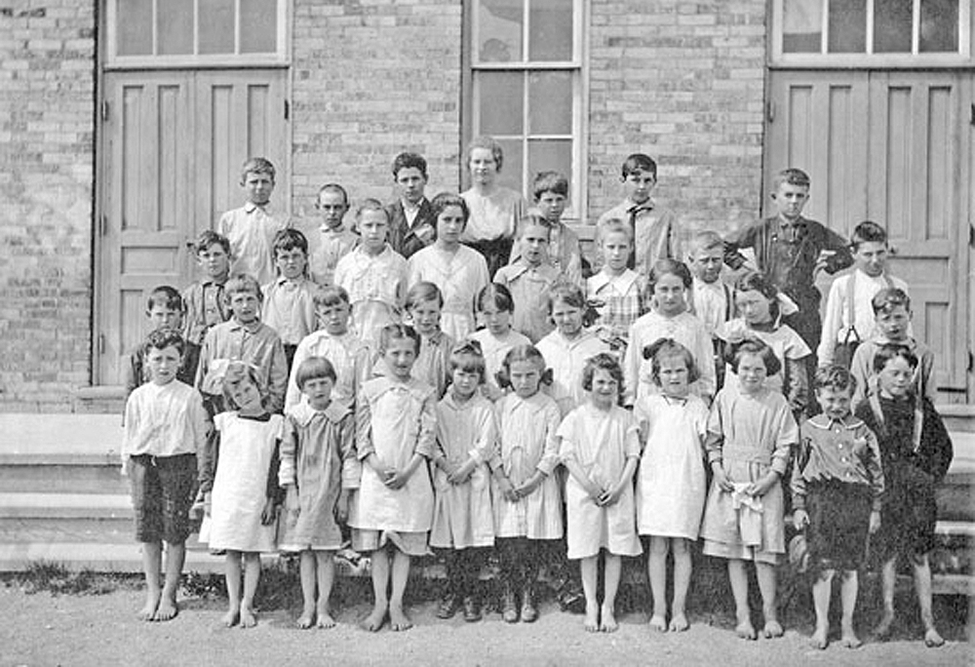

SS#11, Warwick, 1920: In this post-World War I period the Union Jack is very prominent. Back row: Cecil Reycraft, Helen McKenzie, Clara Parker, Florence Edwards (teacher), Margaret McKenzie, ?, Stan Edwards Front row: Beatrice Gault, John Reycraft, Velma Parker, Donald Edwards, Dorothy Jariott, Jean Spalding, Muriel Reycraft, Cecil Parker, ?, Gordon Reycraft. Courtesy Watford Historical Society.

The survival of school records has been decidedly uneven. Some schools appear to have no known extant records, while a remarkable number of registers and trustee records have survived from others. In 1937 the Ontario Department of Education mandated that each school section make a “concise history of the origin of the school.” The resulting record for SS#8 explained that the School was first begun in 1842. The school lot and school stove were rented for 18 Shillings, 5 Pence. The school term went from January to July. The teacher’s salary was paid by persons in the section paying 3/4 of a penny on the pound on rateable property. There were 44 pupils in the early school. In 1854 the teacher was Adolphus Blush, the first there is any record of. He was paid 4 £ per month. Adolphus Blush later settled in the section and became a trustee taking much interest in the affairs of the school. Asa Schooley and Ira Bearss were among the first trustees, later S. M. Eastman and Alonzo Sweet. Wood was provided for the school by each family bringing a certain amount. However wood was plentiful and cheap and easily provided. In 1858 SS#8 & 9 sections were united. The united sections were called SS#8. In 1860 a property tax law was passed to pay the teacher’s salary and other expenses, excepting wood which was now provided by each pupil being taxed ¼ cord wood.22

As for the teaching staff of the period, there seems to be a marked consistency in the memories of students from the mid-nineteenth century that there was a uniformity in corporal punishment meted out to students. Martha (Eccles) Kenward would later describe how, “There was one teacher — a Mr. Sand — and he was a fine man, but he had a quick temper…. I remember one morning, at prayers, my cousin threw one of the girl’s bonnets over the girls’ heads and — well, he was a whole week at home for he couldn’t sit down.”23 Born in the late 1840s, Isabella (Marshall) Lowry attended a school as a child and remembered

SS#4 Birnam: This school was built in 1879 by Howden Bros. of Watford. It opened in January 1880. Th e first teacher was T. Kingston. Courtesy M Miner.

I tell you we daren’t bring home any tales from school when we were young, either. I remember one day mother said to me, “What have you been doing to make your hand black, Bella?” Well, the teacher and I had a slight difference of opinion that morning. His arguments were backed with a split ruler, though, so I came off second best. The teacher was Murdo McLeay, you know, and he boarded at our place. I was afraid to tell mother just what had happened, so I said I guessed I’d spilt some blackberry juice on it. Then I ran out of the kitchen door in a hurry to drive the calves to water, which was part of my share of the chores.24

Official records that survived from the early period also served to show how complicated the division and redivision of school sections could be. In the instance of SS#2, one early writer explained:

According to the township clerk’s records, S.S. No. 2 dates back as far as February 22, 1853. Of course at this time the section comprised a much greater area. From a motion made on June 12, 1855, we conclude that S.S. No. 2, the second section to be established in the township, originally extended through Concession No. 1, S.E.R., No. 1, N.E.R., and Con. 2, N.E.R., from Lot 21 westward and included what later became S.S. No. 15.25

Given the concerns expressed by inspectors about the health and desirability of the original log structures that served as schools, there seems to have been a concerted effort to replace most of these structures by the end of the 1850s and early 1860s. That having been said, the state of schools continued to vary throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century. According to a history of SS#8 prepared in 1937 using the school’s own records:

In 1863 the old log school was becoming unfit for use, and thus in the same year authority was given to the trustees to obtain a site for a new school house as central in the section as possible. This was decided to be bought from Asa B. Schooley. It was decided the school should be built by Daniel Steels of Melrose. On Aug. 24 1864 the building of the new school was commenced by Mr. Steels. This was built on ½ acre of land. The school grounds were fenced, gate put up and toilets. Later in 1866 a well was dug. In 1869 a new desk was purchased and 1876 the school was painted.26

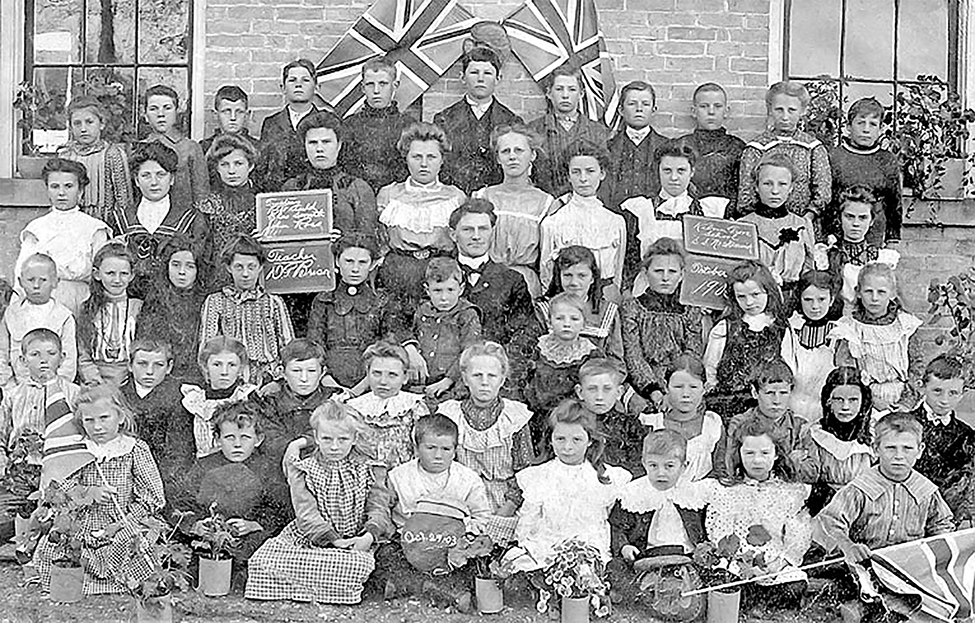

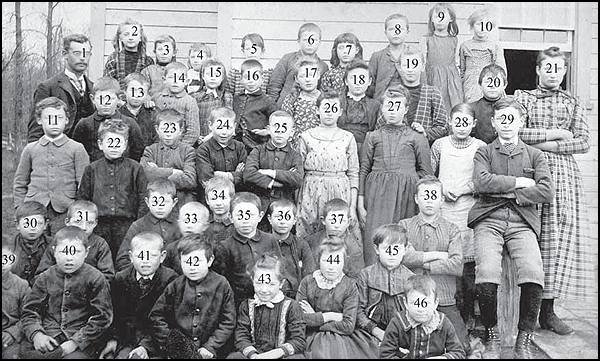

SS#2 Kelvin Grove, 1903 Back row: Elva Smith, Gordon Perry, Ray Janes, Walker Hobbs, Cecil Janes, Basil Hobbs, Fred Th ompson, Earl Cook, Kenneth Ross, Minnie Leggate, Herb Thompson. Fourth row: Grace Auld, Pearl McCormick, Verna Smith, Alice Anderson, Lily Karr, Addie Janes, Kate McKenzie, Delia Th ompson, Merle Leggate, Annie McKinney. Th ird row: Robert Ross, Ella Bartley, Meryl Dodds, Amy Smith, Leila Anderson, Clare Smith, D.G. Brison, (teacher), Pearl McLeay, Ruby McCormick, Emma Barnes, Annabel McKenzie, Anna Auld, Alma Leggate. Second row: Lloyd Smith, Victor Barnes, Annie Hobbs, George McCormick, Annie Barnes, Amy Leggate, Oscar Ross, Dorothy Wordsworth, Willie Wordsworth, Mabel McCormick, Orville Richardson. Front row: May Barnes, Wilbur Janes, Cora Smith, Franklin Auld, Donna McKenzie, Lloyd Cook, Mary McKenzie, George Leggate. Trustees: Robert Auld, John Ross, Charles Smith (names on board). Courtesy Warwick WI Tweedsmuir Books.

The Union School SS#1 Brooke and SS#13 had been built in about 1843 out of logs. However, a new school was soon needed and ultimately the building was replaced with a larger structure on Lot 14, Con. 14 across the township line in Brooke. This building served its purpose until a new frame structure was built in 1874, after trustees had managed to secure more land to enlarge the grounds. By the turn of the century many area schools had either replaced or were planning on replacing frame structures with more substantive brick structures. However, in 1903 the trustees of the union school opted instead to provide the 29-year-old structure with a brick veneer, add new cloak rooms and replace the desks and other furniture.27

Union School SS#13 Warwick & SS#1 Brooke, 1948–1949 Back: Elaine McNeil, Edith Jones, Orville Eastabrook, Roy McLean (teacher) Front: Ronald Edgar, Jimmy Jones, Larry Jones, Lois McNeil, Bruce Greer. Courtesy P McLean.

The division of the old SS#11 and SS#12 union school section into two separate areas was accomplished in 1869. In 1870 a new school was built to accommodate the students from SS#11 on the northeast corner of Lot 23, Con. 3 SER. When further adjustments were made to the school section boundaries in 1885 with the severing off and construction of SS#17, the trustees and ratepayers of SS#11 decided that the school’s location had lost many of its advantages and needed to be more centrally located for those students remaining in the section. As a result a 99-year lease was signed by the trustees for a half acre lot on Lot 26, Con. 2 SER for $50 and the frame school building was bodily moved to its new location. Ultimately this building would be replaced by a brick structure in 1912, and the old school building was sold for use as a driveshed.28

In 1883 a meeting of the board of trustees for SS#6 established that a new school building was needed and inquiries were made about the economy of building either a frame or brick school. A proposal was brought before the ratepayers of the section for the construction of a brick school that would include a classroom and two rooms euphemistically called “offices four by six [with] two holes in each.” The costs, the ratepayers were informed, would amount to $1,400. Ultimately the board was given approval and the right to issue debentures for the building’s construction. That summer permission was also granted for the digging and bricking of a well on the school property. Over the next number of years further improvements were made including the planting of trees and the hiring of a school custodian, William Barber, “to light the fires by eight o’clock each morning of school, scrub the school house floor, and wash the windows twice during the year, spring and fall at a salary of eighteen dollars to be paid quarterly.”

There were also difficulties that had to be addressed as there appear to have been problems by 1892 of students engaged in “malicious damage done to the school” with the result that the parents of such offenders would be held financially liable. By early 1893 there were also attempts by the school board to take “some steps to ward off the diphtheria which is prevalent in the village of Watford.” In addition to the structural and physical health of the building and students, there were concerns over the school population’s spiritual well-being when it was reported “that the copy of the scripture readings in use in the school” had been “removed by some parties unknown on or about the twentieth of June eighteen ninety four….” As a result the board authorized the secretary to procure a replacement copy.29

THE SCHOOL EXPERIENCE

Each school and school section was made up of its own particular collection of personalities that would make the experience of education and the character of a school unique. At the same time, however, the uniformity of curriculum and other commonalities would make for certain shared experiences.

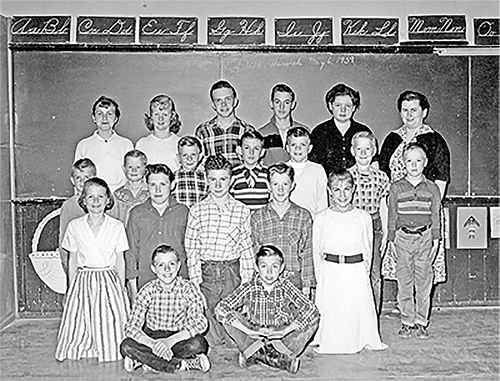

SS#6 Warwick, 1959 Fourth row: Marie Bryce, Karen Hollingsworth, Lyle Hayward, Joe Hollingsworth, Linda Smith, Mrs. D. Shea. Third row: Tom Kelly, Rob Manders, Doug Muxlow, Rick Hollingsworth, Ken Muxlow, Richard Manders, Murray Duncan. Second row: Peggy Hollingsworth, Charlie Duncan, Ray Maher, Allen Redmond, Marilyn Hollingsworth. Front row: Bob MacLachlan, John Bryce. Courtesy D Shea.

In 1895 the family of Richard Hamilton and Alvira (Hill) Zavitz, having buried their only son, a victim of typhoid fever, decided to leave their farm near Shipka in Huron County for a new start in the area of Birnam in Twp. Tragedy, however, seemed to follow the family, for one of their seven daughters, Minnie May contracted diphtheria, known locally as “black plague” and succumbed to the illness. The family, however, remained in the Birnam community on their farm, while Richard took extra work in the winter at the local blacksmith shop. Their surviving daughters attended SS#4. As Etta (Zavitz) Lewis wrote:

We mostly walked to School…. Sometimes Father would take us and we would pick up kids all along the way; the Hagles, Grahams, Crones, Mellores, Cables, and others. My sisters and I all had real little tin dinner pails and not just a honey-pail like some. We had some really cross teachers, some not; I recall Peter McGibbon, David Brison and others. I never had to be punished with the strap or cat o’ nine tails, as we called it. I remember a teacher using it on one of the little Luckham girls, and she was so frightened, she made a puddle on the floor. One time some of the boys climbed in a window at night and cut the strap all up. She never did find out who did it.30

Warwick & Brooke Teachers’ Association, 1875: On Saturday last, the and Brooke Teachers’ Association was held in the School House. The President, Mr. John Tullock was in the chair. Only 17 teachers appeared. The minutes were read and confi rmed. Mr. W. G. Shaw showed his method of teaching local geography which was highly approved. Miss Carroll showed her method of conducting a second reading which was generally approved. Mr. Bodaly’s mode of teaching general geography was endorsed by the Association. The following offi cers were elected for the coming year, Pres., G. W. Ross M.P.; 1st Vice Pres., John Tulloch; 2nd Vice Pres., Miss Carroll; Sec. and Treas., Robert Tanner; Librarian, Miss Lamb. The business report of last year was read by the Secretary and approved. It was moved, seconded and carried, that the next meeting be held in the Watford School House, on the second Saturday in November. SOURCE: Watford Guide-Advocate, August 27, 1875.

Many of the experiences of the Zavitz sisters would have been familiar to most students across the township. Attending school in the first decade of the twentieth century, Russell Duncan recalled his time at SS#6:

A lot of boys and girls had a short school term. Some three miles to walk. Didn’t know [how] to write or read. Our school was just 40 rods across the road [from our farm] and 1 mile from Watford. The teachers were all from Watford and, with snow three feet deep, many only got $400 for a year’s salary. With 20-30 pupils, a big box stove to heat the school. A real cold spell would have all the ink wells frozen solid, but just the fourth grade had ink pens. Lead pencils and chalk with slates to write on. Slow learners had to stay after school and maybe write a mistake 30–40 times till they got it right. You never forgot after a spell like that. The teachers had eyes in the backs of their head sometimes and knew how to use a strap sometimes. Many a strap was stolen or cut in pieces. There were scholars bigger than the teacher and 3 guys were 17–18 years old who just went to school in the winter time. There was a big pond 40 rods north from the school to skate on. The teacher would have to go back near half way to ring the bell calling the class back to work. Any late arrivals would have to stay in at recess time.31

Schools were mandated by the province, but very much creatures of the local communities they served. Since trustees came from amongst the local ratepayers and localized sensibilities, pressures and prejudices frequently influenced the ways schools were run. While the system could, and often did, work well, inevitably there were difficulties and people hurt in the process. A case in point was the situation at SS#8, south of Arkona, where the attitudes and decisions of the close-fisted and at times unimaginative school board in the early 1920s led to a bewildering succession of teachers. The students involved had little opportunity to influence the decisions made and were often hapless witnesses, and victims, of school board politics.

Ethel Stonehouse had been engaged as the teacher upon the departure of Olive Oakes32 in 1919, and would remain at SS#8 for two years. Russell Dunham assessed that Stonehouse “was an excellent teacher.” Stonehouse’s departure marked the end of relative stability in the classroom. The academic year spanning 1921 and 1922 was to be particularly turbulent and unsettled at SS#8. With the departure of a much-loved teacher Russell Dunham explained:

Well we had a Miss Downs for one month, and they found out she didn’t pass her art and they had to let her go. And she was Catholic and used her Catholic prayers which she shouldn’t have done, but that didn’t worry us. And then we had the next teacher, Miss McLeish, she stayed until Easter and there was a bit of problems in the school and they let her go.33

As Dunham remembered it, he was never entirely sure why Miss McLeish was let go, although he recalled that “some of the parents were very upset in the section and they held a school meeting one day about it, I’m not exactly sure what it was all about.” One of his older sisters, Cecile, explained that the problem was that Miss McLeish was rather cross and “She used the strap quite liberally.” Apparently the parents of the children who were at the receiving end of this punishment were provoked and had been the ones who had demanded a meeting. Suffice it to say Miss McLeish did not weather whatever storm of controversy swirled around her.34 Following her dismissal Russell explained that the third teacher in less than a year was “Mr. Wearing, and he was weary; he went to sleep one day at noon hour and we were having a great time playing ’til some of the girls thought they should wake him up.”35 Cecile explained that:

It was funny for us, because he [Wearing] was left handed [and] he worked with his left hand while working on the board. One day Vera [Fitzsimmons] and I became concerned — her and I were the older girls in school, she was in junior fourth and I was in senior fourth like grades seven and eight nowadays — … [for Wearing] was sleeping out on the lawn. It was one o’clock and no teacher. Well Vera and I said, “Well should we wake him up or shouldn’t we?” So at last we woke him up. And if I didn’t have the good grounding in the junior grades I would never have passed my entrance. Because it wasn’t a good year at all with three teachers.36

SS#8 Warwick, 1920 Back row: Edgar Sitter, Ted Herrington, Grant Evans, Miss Ethel Stonehouse, ? Dunlop, Wilbert Eastman, Harold Evans. Third row: ? Smith, Leonard Sitter, Edna Dunlop, Ethel Dunham, Alice Wambaugh, Vera Fitzsimmons, Harold Dunlop, Lawrence Benedict. Second row: Frank Muma, George Wambaugh, Dean Percy, Jean Butler, Alice Wambaugh, Evelyn Cochrane, Cecile Dunham, Hetty Percy, Everett Butler. Front row: Russell Dunham, Winnie ?, Margaret Wambaugh, Mary Wambaugh, Noreen Cochrane, Corena Sitter, Marguerite Herrington, Thelma Smith, Hazel Dunlop, Ellis Butler, Harry Wilson. Courtesy R Dunham collection.

Whether or not the parents of the section heard about this incident, Wearing ended up serving out the rest of the term, although he did not do so in the best manner. Russell explained that

the Department [of Education] sent out the exams on one big sheet of paper and he [Wearing] was supposed to cut off the first exam and give it to us, but the first day of the exams he gave us the whole sheet so we had a chance to know what all the rest of the exams were going to be the rest of the days.37

After having a spate of three teachers in short order things seemed to settle down a little, although Mr. Wearing’s contract was not renewed. Russell noted that following Wearing’s departure the trustees hired

Miss Stewart, and she was an excellent teacher, and she asked if they could give her a raise at Christmas time, and so instead of giving her a raise they told her she could go and they hired Miss Hobbs, who lived up the road a ways. The local trustees were looking for the cheapest teacher, not always the best one. And so Miss Hobbs finished the year out…. I guess she taught a full year — finished that year and the beginning of the next one — and then Miss Barry came, and she was an excellent teacher, you couldn’t beat her.38

While the good Protestant ratepayers of SS#8 may have been dismayed upon learning that Barry was a practicing Catholic — a fact that may have been kept initially from the local trustees — she was much beloved by her students and remained at SS#8 for three years.

Because many of the teachers in the individual schools came from outside of the school section, at times even hailing from other counties across the province, inevitably they would board with one of the local trustees or ratepayers, with the result that they were integral members of the local community, and their paths would cross with their pupils on a regular basis. Some students had the honour — or dubious distinction — of having the teacher board in their own homes. Writing of her days at SS#4 near Birnam in the late 1890s and early 1900s, Etta (Zavitz) Lewis explained that “The teachers nearly always boarded out at the Harpers, Vances or Luckhams, and mother was always very anxious to have them come to supper at our house.”39

SS#15, Warwick, 1933: Note the two entrances, one for girls and one for boys. Standing: Elaine Brush, Lloyd Maw, Frances Learn, Lloyd Barnes, Elva Barnes, Noreen Mathews, Marian Holbrook, Bernice Yorke, Keith Yorke, Bill Blunt, Marian Fenner behind Velma Holbrook, Teacher: Loretta Logan behind Olive Dann, Bill Prince, Isabel McKay, Dorothy Ferguson, Wilfred Goodhand. Kneeling: Ralph Learn, Clayton Stewart, Bernard “Tim” Barnes, Stuart Smith, (Lloyd Stewart behind Stuart), Norman Cosens, George “Chap” Smith, Doris Barnes and Janet Hawkins. Sitting: Bob Blunt, Jean Roberts, Lorne Goodhand, Harvey Blunt, Margaret Ferguson, Nina [Christina] Stewart, Ella McKay, Bailey Yorke, Doris Holbrook, Leroy “Benny” Dann Absent: Doris Fenner, Marjory Blunt. Courtesy WI Tweedsmuir Books.

Recalling school days in the 1930s, Janet (Hawkins) Firman wrote:

I started school at S.S.15 , located on the Egremont Road, where forty pupils were taught by Mrs. Loretta Logan. School teachers such as Jessie Cran and Ruby McMillan boarded at our place during their teaching terms at the school. I well remember Ruby McMillan giving my brother George and me a large chocolate bunny at Easter. How we looked at and admired it before gradually eating the ears, nose and tail. This was something we had never before received.40

Whether they boarded at the homes of local trustees or other ratepayers within the community or lived in homes of their own, teachers had to keep up a certain code of conduct; they were constantly under the scrutiny of the local communities they served. In the late 1940s these strictures may have been slightly less than in earlier decades, but nonetheless, they had to be followed. George O’Neil and his wife Frances (Field) O’Neil taught at neighbouring schools. As Frances explained:

Every month the Lambton County Film Board would deliver educational films with a projector, to be viewed in the schools. These films were shared between schools so one school would travel to the neighbouring school to watch the films. Parents were very kind in providing the transportation for this extra bit of learning.41

Teaching Music in Warwick: Irene Ellerker Houghton was one of the fi rst music teachers in the rural schools of . She relates that the music program in Twp. was begun in 1937, a year after Bosanquet Twp. She taught in the schools north of the Egremont Rd. from 1937 until June 1945. In the area south of the Egremont music was taught by Florence McRorie Main. Irene taught in fi ve schools: on the 2nd, 4th and 6th Lines, at the Birnam school, and at the Union school (which included students from both Bosanquet and Twp.) at the end of the 6th Line. As well as learning about music and singing, each school always presented a special Christmas concert featuring music. When Irene began teaching music, she was paid about $50 per year by each school. Half the amount was paid by the school board at each school and half was paid by the Ontario Department of Education’s Music Department. SOURCE: Doris Leland Ellerker memories, 2006

George taught at Bethel School and Frances taught at Kelvin Grove. It was these two schools that shared the films, with France's school travelling to Bethel to see them. One story that circulated was that George and Frances held hands during the films. With parents attending the showings of the films and the nature of the times, this story is certainly interesting and funny but a very creative work of schooltime fiction.42

The quality of education depended upon the teachers and the trustees but also on individual students. Certainly some students excelled in their studies and showed a particular aptitude in specific subject areas. Wib Dunlop, a student at SS#8 (“The White School”) recalled:

Out of the twenty-seven I was seventh when I tried my exams. My teacher said I was her pet. I guess I was. That is one thing that I fall down [on] to this day. That was my poorest subject. Writing. English. Arithmetic I could do one hundred percent, no trouble. We had a question one day. In no time flat I had it done. Teacher said get your work done. I said I got it done. Well, it was wrong. Do it over again. So I did it again. I came up with the same answer. Lo and behold the answer in the back of the book was wrong. She never got over that. Arithmetic I could really do.43

For so many students the education they received at their one-room school houses was the only formal education they would get. Even some of the best students did not expect to go on to further study as it was simply not a family expectation; in other cases the costs involved in getting them to continuation schools or high schools were seen as prohibitive. As Wib Dunlop explained, following his six years of education at the White School and passing his high school entrance exams with flying colours, circumstances intervened. Years later he recalled:

I was supposed to [go on in school], but I had to stay home and work. My father was partly crippled. We were threshing so I had to stay home and work. I didn’t get any further. My teacher wanted me to go on to Continuation School. You see in Arkona there was two years of Continuation School, but I didn’t get there. I was supposed to go but I didn’t get there.44

HIGHER EDUCATION

During the early part of the twentieth century, it was very often daughters who remained in school longer than their brothers. Sons were generally expected to leave school earlier to help out on the farm, enter the family business or find other work to contribute to the family income. It was far less socially acceptable to have a daughter go out into the workforce, and this often afforded some girls a slightly longer education. Yet while girls could remain in school longer, for many their ambitions of pursuing higher education and careers of their own were hindered not only by family economics but also by deeply-entrenched social expectations. For Ethel (Dunham) Fisher education ended abruptly when she finished her elementary schooling. Her parents said that they could not afford the tuition and to her eternal regret her dreams of becoming a music teacher were dashed. She recalled bitterly, “I didn’t get to Continuation School. Mother thought I should stay home and help her.” It was also noted that her parents did not see the point in a girl getting too much education as they expected that their daughters should marry well and be provided for.

SS#8 White School, 1915: Wib Dunlop’s brothers, Joe (age 12) with checkered hat, and Paul (age 8) behind boy with solid dark toque are in the photo, as well as his cousins Bill (dark toque) and Clare (centre front). Courtesy W Dunlop.

Some attitudes were shaped by the experiences of others. One area farmer sent his eldest daughter on to high school and then to Normal School to train as a teacher. When the daughter married after only teaching for a few years, her father, disgusted, informed his neighbours that education was a waste of time and vowed that as for his younger children he “wouldn’t educate the rest of them.” Little did he anticipate, however, that when his son-in-law died prematurely his daughter would return to the classroom for many years as a means of supporting her own children.45

For those students that went on with their education, there were certainly various options available to them, but very often, especially for those students living in the more rural areas, those options involved a great deal of travel. Until the 1880s there was no institution of what might be termed secondary education in the township, even in the larger centres of Watford and Forest. In Lambton County the only institution of post-elementary school education was located in Sarnia, in the form of the District Grammar School which had been established in 1844.

In 1871 the Department of Education abolished the existing structure whereby District Grammar Schools, in place since the reforms of Bishop John Strachan in the early nineteenth century, were the sole form of secondary education. They had been largely developed to enable male students destined for the professions to receive their education. In place of these institutions was the creation of two new types of school. High Schools were set up to provide male and female students education in English and natural sciences with an emphasis on agriculture and to provide courses of study geared toward students headed into commercial enterprise. The second institution was the Collegiate Institutes that were the real heirs to the old Grammar Schools, emphasizing a classical education and providing mostly male students avenues to enter into university.46

Despite this legislation these new institutions of secondary education did not spring up overnight; those students in Watford and that wished to pursue further education had either to make their way to the Watford Station and travel on a daily basis to school in Strathroy or to make arrangements and pay for room and board in centres like Strathroy, London or Sarnia. In 1875, however, a movement started within Watford to establish a secondary school. There was some support, but also much opposition. Some ratepayers in Twp. and possibly within Watford itself were opposed to the idea, fearful that it would lead to exorbitant costs and lead to financial ruin. J. A. Tanner predicted such an institution would possibly degenerate “into beggary.” The difficulty seems to have been largely that, in order for such an institution to be built, cooperation would be needed between the township and the municipal council of Watford itself. The proposed high school would need the financial backing of both municipal governments, and those proponents of it needed to persuade their apparently more reluctant rural counterparts that such a school would be of benefit as well as financially sustainable. After enticing some ratepayers in Brooke Twp. to throw in their support, a new High School Board was formed in 1888, and classes began to be held shortly afterwards in Watford’s old town hall. In 1891 the fledgling board approached Watford Village Council with a proposal for the construction of a permanent school building. Ultimately Council approved the plan and agreed that $7000 would be set aside for its completion. After a series of disputes over the school’s location, the tender was granted to A. Gerhard for $4,977 and construction began. The building was partially opened by the end of August 1891, although the four-classroom structure was not officially opened until January 1892. While enrolment initially stood at seventy-six students, the numbers quickly increased and soon some classes were occurring in the newly constructed Watford Public School as well as within the Watford Public Library. The building would serve with these two subsidiary campuses until major renovations were carried out in 1927.47

Watford was not the only option for students seeking further education. A permanent high school had been constructed in Forest in 1890, a full year before Watford, at a cost of $6300 and under the leadership of Principal James H. Philip. The five staff and 160 students were left temporarily homeless after fire destroyed the entire school building in February, 1940, although it was quickly reconstructed. While it did not boast a high school, Arkona established what was termed a Continuation School in part of its existing three-room Public School in 1909. This institution provided the first two years of high school. However, if a student wished to pursue further education they would have to either travel to Watford or Forest or places further afield. The Continuation School experiment remained in place until 1945. With improved transportation, more students were availing themselves of high schools in Forest and Watford, so when the numbers were reduced to only eight students the Arkona Continuation School was finally closed and the students sent to Forest.48

Arkona Public School, 1907:Th is building also housed the Arkona Continuation School. Also visible is the back of the Arkona Methodist Church. Courtesy Arkona Historical Society.

SPECIAL DAYS

Until after World War II, most students’ formal education was confined within the walls of their one-room elementary schools. One of the highlights of the school year for many students was the annual school fair, sometimes connected to the various agricultural fairs. On October 7, 1880 a writer identified only as “Annie” of penned a letter to the editor of the Watford Guide explaining:

I hope the mothers and fathers of our young people are prepared to take their children to their County Fair next week. It is a part of education that should not be neglected, and opens their eyes to comparisons, while exciting a spirit of emulation. “We have as good as that at home,” I heard a young lad say one fair day when examining the fruit, and the next year his name was on the list of prize winners. So it is in many things, and I have often observed that children seemed brighter and better for their journey, besides feeling that they were of some importance in the world when they are allowed the trip with the older people who may hitherto have enjoyed the privilege. Let the boys have some poultry or animal; the girls some flowers or fruit they can watch the season through, and then exhibit as the result of their care. Even if they do not win a prize (and all cannot), the trail will not be lost, but will incite them to further attempts. If one shows a talent for housekeeping, let her exhibit canned fruit or a loaf of bread of her own making; and if the boys have any mechanical skill or genius in any direction, let it be encouraged and made the most of. The contact with others, the varied display, the diversity of arrangements and the method of exhibiting will not be lost to their young observing eyes; and if father and mother instruct them in the survey they will be amply repaid by the keen, eager scrutiny that will be given. By all means take the children to the fair.49

Given that Twp. had at least four major “urban” hubs, in the form of Village, Watford, Arkona, and Forest, there was no single or centralized school fair for the entire township. Nonetheless these fairs were an opportunity to bring students from different schools together to showcase their work and compete in various activities. As Janet (Hawkins) Firman explained “I remember the pupils [of SS#15] marching down to the Village Fair held at the old Orange Hall. That was a big day out. Judging of school projects, fruits, vegetables and baking took place in the hall. Calves were tied up to the fence for judging.”50 In addition to the local school fairs there were always the local fall fairs in which schools generally played a role. As teacher Frances (Field) O’Neil recalled, her students of SS#2 Kelvin Grove participated in the Forest Fall Fair in the late 1940s. The fair would see the students “marching in costume from downtown Forest to the Fair Building. Prizes were given for marching, costumes and the school with the best school banner.” As Frances further explained, one year her “mother, Jennie Field made all the costumes for the entire Kelvin Grove School.”51

While the school fair was an important annual milestone, so too was the Christmas Concert that most schools held on an annual basis. While some schools held them in the school buildings themselves, others held their concerts in conjunction with the nearby church. Recalling those times at SS#4 at the end of the nineteenth century, one student explained that:

We didn’t have a concert in the school at Christmas, these were always held in the upstairs of Bethel [Methodist] Church. People would come for miles around. I guess there wasn’t anywhere else to go. I used to sing and had a good voice then. There would be a long clothesline rope hung right across the front of the church, with pretty handkerchiefs all hung on it, and that was our gift from the Sunday School. Sometimes we would get a book. Some parents would bring things and put them under the tree for their children, but our parents didn’t. One night after the concert we got to stay all night with Louisa Logan. Even though there wasn’t any heat in the bedroom we had fun. And sometimes we’d go to house parties at Luckham’s. What fun we had playing games.52

A generation later SS#4 held a concert in the school building. For Lloyd Alexander Haney the Christmas concert in December, 1927 held special memories because

he was unexpectedly asked to be Master of Ceremonies because the regular person did not show up. Being only 8 years old he said yes. So he stepped up to welcome everyone and said, “I’ve been asked to undress you, sorry ‘address you’.” It brought a great laugh but he carried on.53

The concerts carried on at SS#4 and in the late 1940s Ron Faulds recalled that

[i]n the wintertime… we had oyster suppers & organized crokinole. At Christmas time, our school concert was like no other. Our teacher, George O’Neil, loved music and his concerts were elaborate affairs! About a week before Christmas the trustees came in and built a stage. There would be plays, music and solos, and quartets. It was quite a display of school talent!54

Queenie (Edwards) Benedict, who taught at SS#8 just south of Arkona in the 1930s, recalled that

We’d start… fairly early in November to look up material for a rural Christmas Concert because all the people in the area looked forward to the Christmas Concert…. The thing was, you’d choose the most interesting material, but you’d also have your pupils’ names in mind and make sure that each child all through your classes would have about the same length of time on the platform…. Then you’d start in practicing about… maybe a little bit before the first of December and that would take the English part of our lessons. We still had our spelling and Arithmetic but come along in the afternoon the English went into this practicing. It was a good experience.55

While the Christmas concert and fair days came only once a year, there were other special days to break up the usual routine. Attending SS#6 Dorthy Douglas recalled:

Our school had a special day for Red Cross and we would bring a dime for donation and another day that was music day and Mrs. Ferguson would come to our school and try to get us to carry a tune. She taught us to play “God the Save Queen” and some of us took turns in the morning banging out that one finger song.56

However, Douglas noted that

Of all the visitors to our school, the one I disapproved of most was Dr. Thompson from Arkona Medical Office, who came to give us our polio shots! If you had a reaction to the shot the next day you would have to go to his office and naturally I did! I was just scared to death of that man with the bad hair and the big baggy pants!57

Red Cross, music days, and the dreaded visits by local physicians aside, there were also more extraordinary days such as the bus trip the students of SS#6 took to Detroit, Michigan. As Douglas explained,

Our bus trips were adventures that cannot be forgotten! The trip to Detroit Zoo stands out for me. We were split into small groups with a parent to help supervise each. Anna MacLachlan was my super and she got lost! I couldn’t find her anywhere and I spent most of my time there looking for her. When I found her she set me in the bus and told me to wait there for everyone else — so I figured all of them were lost! I did especially enjoy the Ford Museum and always intended to return.58

While there may have been improvements in terms of job security that had been absent in the earlier part of the century, one teacher in the post-World War II era recalled that there were difficulties that had to be endured. She noted that with so many students to teach and supervise, she regretted that at times “I could not always provide the one on one teaching….” Similarly all was not necessarily idyllic for the rural teachers, who were often isolated from friends and family. She noted that “[s]ometimes the days were very long. During my first year, my father passed away.”59

SEPARATE SCHOOLS

While the religious makeup of the township has long been varied, the majority of the population, until well into the twentieth century at least, claimed a form of adherence to a multiplicity of Protestant denominations. The Roman Catholic population, however, was a large minority. Consequently, while legislation had been established allowing for the creation of separate schools for Catholic children, their numbers were never sufficiently strong in one particular area of the township to warrant the creation of a separate school. As a result the children of Catholic families attended the various one room “public” schools that adhered to a fairly ecumenical, if nominally Protestant, religious component. Certainly there had been Roman Catholic teachers in some of the schools, beginning as early as 1850 and continuing on for more than 80 years.

St. Mary’s Roman Catholic School was built in 1954 on Hickory Creek Line. Courtesy J Boere.

With the end of WWII, the Catholic minority in the township was bolstered considerably by a major influx of immigrants, mostly from the Netherlands, who came and made Warwick, Watford, Arkona, and Forest their homes. The northern end of the township fell within the Parish of St. Christopher’s Roman Catholic Church in Forest, while the southern end was centred upon Our Lady Help of Christians in Watford. Given that those children who attended either Catholic church had most of their formal education in public schools, most of their religious training was left to their parish priests outside of normal school hours. Local parents footed the bill for teaching sisters from Sarnia to come and instruct their children on catechism.

In 1954 St. Mary’s School, numbered as Roman Catholic SS#20, was opened on the 6th Con. NER of Twp. The school housed some forty students, many of whom were the children of recently-arrived Dutch immigrants. The school was officially opened a month after classes began, in October, 1954. While those families who supported the school had their taxes diverted to its maintenance there was an additional charge of $2 per month for each child attending, payable by the parents. Textbooks were provided but students were responsible for supplying their other equipment. With the school population burgeoning, St. Mary’s finally joined with St. John Fisher School in nearby Forest in 1964 and its school population was bussed to the location in town.60

St. Peter Canisius Roman Catholic School, Watford, was the successor to St. Christopher’s on Nauvoo Rd. Courtesy J Geerts.

Meanwhile, just north of Watford, St. Christopher’s School (RCSS#2) was built on the corner of Hwy 7 and County Rd. 79, opening with Mrs. M. Beaudoin as its first teacher. Until the school opened the students in the area attended Kelvin Grove School. The local Catholic community, many of whom came from the Netherlands and Belgium, had been anxious to build their own school, and had been aided in their efforts by those who had experience in the establishment of St. Mary’s the year before and from Father Coppins, a Dutch priest who lived in Delaware. The school’s establishment conflicted, to a degree, with the plans of Township Council, which was at that time attempting to amalgamate all of the school sections with the idea of building a larger central township school. They were not at all anxious to have at least 40 students leave the public system, nor to have future Catholic immigrants into the area follow the example. Ultimately, however, with legal help from Catholic authorities, the way was paved, a plot was purchased from Peter Rombouts, and a new brick school was constructed.

In her 2005 history prepared for the 50th anniversary of St. Christopher’s, Julia Geerts noted that, as there was yet no Catholic school in Watford itself, many children there would travel out to St. Christopher’s to receive religious instruction. She explained that “On Saturdays the main classroom at St. Christopher’s sometimes filled with 60 older children while the small ones, about 35, were packed in the entrance hall to prepare the students for the sacraments.”61

SS#16, 1947 Back row: Alvin Garside, Jim Sayers, Jim Peterson, Murray Bryce, teacher Frank Moff att. Middle row: McEwen Bryce, Jean (Sayers) Wilcocks, Pat (McCormick) Clark, Marianne (Th ompson) Brooks, Muriel (Th ompson) Butsch, Bernice (Bryce) Slack, Bruce McEwen, Audrey (Bryce) Green. Front row: Wes Bryce, Bill Garside, Kay (Bryce) Harper, Pat (Claypole) McGill, Ruth Peterson, Ronald Bryce. Courtesy J Sayers.

Julia went on to say that keeping teaching staff for more than a year proved to be difficult as “teaching grade 1–8 immigrant children English as a second language could be very challenging.” In 1957–58 teacher Joyce Trembley received $2,200 as a beginning teacher, while in 1961 Elizabeth Whelan was paid $3,700. Miss Whelan taught 34 students in 1962–3. The students walked, biked or were car pooled to the school. Annie Rombouts cleaned the school with the help of other students. The grass was rarely cut so in the fall the playground had a lot of interesting hiding places in the tall grass and weeds.62

St. Christopher’s remained open until 1964 when all of the Catholic schools in Brooke, Watford and southern were amalgamated and met at St. Peter Canisius School in Watford.63

St. Peter Canisius School had only been formed in 1957 and the building was begun in 1958, but as work was not completed until late in the year, its 88 students met initially in Watford’s Lyceum Hall. In November the students were transferred to the new building. In January 1959, St. Peter Canisius was officially opened by His Excellency Bishop John C. Cody. Over the next several years the school population increased, necessitating expansion, which was further needed with the amalgamation of the various Catholic school boards.64

THE MOVE TOWARDS CENTRALIZATION

Even in the 1920s there were discussions among some of the ratepayers of Twp. about the “Consolidated School Movement,” which advocated the amalgamation of various school sections and the construction of larger integrated schools. These would, it was reasoned, provide more educational opportunities than the smaller, more isolated schools in the township.65 Although there were various meetings held looking into the matter, very little actually occurred until after WW II. Increasingly more voices across the province were beginning to suggest that one-room schools were antiquated and far behind the graded schools in urban areas.66

Mindful of these new realities and changing focuses, in May,1949,a meeting of township ratepayers concluded that SS#1, SS#5, SS#8, SS#10 and SS#15 should be combined into one school district. As a result the necessary by-law was passed and the five sections were fused. SS#11 joined in 1951, SS#16 and SS#20 in 1954, and in 1955 SS#2 joined too. The idea of moving beyond a federated school section developed and in May, 1955 the idea of building a central school was formally put forward. Endorsed by school trustees and a majority of ratepayers as a whole, a committee of seven men began to investigate.

SS#16, 1947 Back row: Alvin Garside, Jim Sayers, Jim Peterson, Murray Bryce, teacher Frank Moff att. Middle row: McEwen Bryce, Jean (Sayers) Wilcocks, Pat (McCormick) Clark, Marianne (Thompson) Brooks, Muriel (Thompson) Butsch, Bernice (Bryce) Slack, Bruce McEwen, Audrey (Bryce) Green. Front row: Wes Bryce, Bill Garside, Kay (Bryce) Harper, Pat (Claypole) McGill, Ruth Peterson, Ronald Bryce. Courtesy J Sayers.

As a result of their findings, the Township School Board asked Township Council for approval to construct a six-room central school. Despite some hesitancy on the part of the municipal council, approval was finally given and, after years of discussion, 1957 marked a turning point for the ratepayers and township officials in terms of the township’s education. The centrally-located thirteen-acre northeast corner of Lot 12, Con. 1 SER was purchased from Robert Ross, and architect William Andrews was hired to complete the plan. Once the plans were approved the new $120,000 school building was begun, after the sod turning by Annie Ross and Florence Edwards on May 22, 1957. Initial hopes had been that classes would begin in the new structure immediately after Labour Day,67 however

Delays in materials have slowed down completion of all the classrooms, but the contractor is confident the school, in another two weeks can be completely equipped, except for the large sliding doors, which may be a few weeks late, that will roll back to make a fine auditorium from two of the classrooms.68 These delays meant that classes did not begin for the anticipated 190 students in the new school until September 16, 1957 under the leadership of Principal John Beaton and teachers Beulah Saunders, Hazel Brandon, Florence Edwards, Frank Moffatt, and Lorraine Brand. In the interim, Bernard (Tim) Barnes was hired as custodian and bus driver, and two more local men, William Goldhawk and Lloyd Cook, were also hired to drive buses.69

For more than four decades Central joined its “urban” counterpart in Watford in providing education to those students in the elementary grades in a large, centralized location. Hundreds of students would pass through its halls, some whose families were passing through for varied periods of time, and others for the full eight or nine years. As the school population grew, so too did the building. When five more school sections applied to enter the unified school board and Central School in 1959, two more classrooms were added. Further additions were made in 1961 with another two classrooms, a “gymnatorium” and a room for use by the School Board. Finally, over the year 1966– 67 a nurse’s station, a kindergarten and another classroom were built, in addition to a library resource centre which was also used as part of the Lambton County Library System. However, as the kindergarten room was not completed until January, 1968, the first classes were held in the old St. Christopher’s School.70

In 1968 the Ontario Government passed legislation creating unified county-based school boards. The Township Central School, along with Watford Public School and Watford District High School — renamed East Lambton Secondary School — became part of the Lambton County Board of Education in January, 1969.71

Parent volunteers were important participants in the running of special events such as Play Day, track and field competitions, the cooking of hot dogs on Fridays, and so forth. In 1984 ’s principal, Ken Williams, approached individual parents in the school community about the formation of a Township Central School Home and School Association, to better allow for liaison between parents, teachers and the student body as a whole. (An earlier organization with similar goals had existed during the tenure of principal Ron Mansfield.) With Ron Perry as its first president the organization was launched. The volunteers put on a turkey dinner each year in December for the entire school body, sponsored academic awards, and helped with other school functions. They met regularly and attempted to boost membership and encourage other parents to become involved. Members of the Home and School Association also took on the compilation and publication of annual yearbooks for several years. The Association continued until the early 1990s when it morphed into the Central Interested Parents Association. As one member said, it was simply “important to become involved in your children’s school.”72

Central School Memories: Those who began kindergarten at Township Central School in September 1980 were initially divided into two classes, meeting on alternate days with teacher Donna Thomas. Having been shepherded down the long halls by Principal Ron Mansfield for the first few days of school, the students were soon seated on the golden-coloured carpeting, listening to stories, sorting buttons into colour-coordinated piles, watching as Mrs. Thomas cut up apples into “halves” and “quarters” and talked about “oxidation.” There were morning rituals to learn, including the Lord’s Prayer, the singing of “O Canada” and “God Save the Queen” and even, on occasion, the old Anglo-Canadian anthem — even then more than slightly dated — “The Maple Leaf Forever.” That year the students also performed in a play about Peter Rabbit, were instructed about telling time, learned to write their names, and familiarized themselves with the thermometer. There were other unscheduled and unplanned interludes in the school year, such as evidence of a mouse the class soon christened “Rosie.” After she initially evaded capture she was given the second moniker of “Rosie the Magical Mouse”. Similarly there was an infestation of tiny ants that crawled through the class’s cubbyholes, infiltrated peanut butter sandwiches and generally made life interesting. Some of the students — the author of this piece included — also had some difficulty adjusting to the authority vested in their teachers. Sometimes what appeared to be minor infractions seemed to have potentially life-threatening consequences. When, for instance, the author threw a stick he found lying on the primary yard, he inadvertently hit classmate Tracey Pedden. He soon learned about treason as swarms of his classmates reported the matter to Mrs. Thomas, who stormed across the yard and ordered the terrified youngster “To the Office.” When a stern Mr. Mansfield asked why the stick had been thrown, the fi ve-year-old surmised that, while it seemed perfectly obvious that was simply what was done with sticks, a more sophisticated answer was required to extricate oneself from the mess. The result was a swiftly-concocted fabrication that claimed that “Some Big Kids” had told him to do so. This seemed to suffice and after being given a stern but kindly injunction to ignore “Big Kids” he was patted on the head and sent back outside, where his classmates were amazed to see that he had returned alive. Grade One meant meeting with Mrs. Mary Dalton, graduating to a curriculum divided into “Centres” including painting, cut and paste, math-related activities with blocks, and of course the earliest substantive forays into reading and writing. One of the earliest pieces ever penned (really pencilled) by the author attested to the work of both the classroom teacher and the peripatetic [itinerant] music teacher. The lengthy piece ran “Mrs. King helps us sing and so does Mrs. Dalton.” That year the class performed P. L. Travers’ beloved Mary Poppins and even, slightly disconcertingly to my memory, a transparently politically-correct play retitled Little Boy Sambo (?!). Grade Two was under the leadership of the much loved Mrs. Margery Johnston, delving into our fi rst novel about a Navajo boy, and studying with great enthusiasm about dinosaurs. Grade Three under Bob Wilson led to exposure to J. R. R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, and meant the last year in the primary yard. By 1984 the class had made it to Grade Four under the direction of Mrs. Shirley Metcalfe. It was yet another year of transition, a year that saw students launch into more reading, subjects like Social Studies, English, Math and Sciences, and sitting in rows of first five and then four desks. As this author laboriously recorded in his journal in very imperfect English on October 18, 1984: I’ll start copying down what I did at school. Mr. [Ken] Williams had to teach the grade sevens math instead of us so Mrs. Metcalfe tot us how to read bar graphs and how to make them then we talked about Vitamans A and Minerals iron and Water. Then went out [to] reses at 10:30 and came in and worked at our stories about halloween and began to read the story The Gift from our reader Row-bouts and Rollerskates. had lunch and went for reses agin at 12:20…. The class remained together, with significant departures and additions along the way, until June 1989, having been instructed by ever-enthusiastic and engaging John Moore in Grade Five, Doris Kaempf in Grade Six, who helped stage our musical Canada Is, which toured local nursing homes, followed by Steven Beattie and Agatha Gare in Grades Seven and Eight respectively. The end was celebrated with the usual ceremony and dinner in the gymnasium, followed by a party in the classroom during a terrific thunderstorm. The party included a fight with “streamer balls”, much shouting, dancing, and loud late-1980s pop music on tapes. The following day was the dawning realization that an end had come, a new beginning was looming and that the class would be divided and going, in the main, to either North Lambton or East Lambton Secondary Schools. Final class photographs were taken in front of the recently completed memorial to the late Tim Barnes, who along with his wife, Leona, had been one of the school’s long serving custodians. SOURCE: Dr. Greg Stott

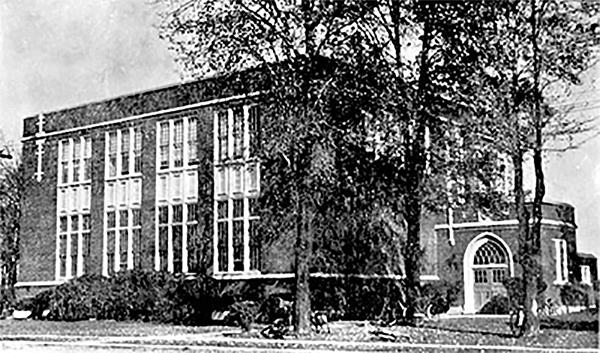

Watford High School, c. 1940: A planned extension of the building was scrapped in the 1940s due to the war effort. Courtesy D Aitken.

MORE CHANGES

In the 1990s a new provincial regime began to make major changes across the province of Ontario. As municipal governments were being restructured, attention was being turned to the province’s education systems. A series of amalgamations redrew the map of Ontario school boards, and Township Central School and Watford Public School found themselves under the mandate of the larger Lambton-Kent School Board. A new provincially-mandated funding formula left many school boards scrambling to cut costs. Difficult decisions had to be made and many rural schools were soon coming under increasing scrutiny in the name of “value-added” and “consolidated” education rubrics. By the end of 2000 decisions and actions were taken that would fundamentally change the face of education in the township. By examining school censuses, cost overruns and the general education map of the enlarged school district, the decision was rendered — despite concerted and sustained community protests — to consolidate the two elementary schools. As part of the same cost-saving drive, East Lambton Secondary School was also marked for closure.73

Man In Motion: (Rick Hansen was a paraplegic who completed a world fundraising and awareness tour in his wheelchair.) I was in Grade Six at Central and remember the building excitement that preceded the visit. On the day – November 25, 1986 I believe – our regular teacher, Mrs. Doris Kaempf was away and left our class with a Geography test. If the anticipated arrival of “The Man in Motion” didn’t make concentration difficult enough, our classroom was on the east side of the school and faced directly onto the driveway where hundreds of students from other area schools were being bussed in and assembled. The noise was tremendous. Mrs. Edwards, our substitute teacher, made it clear that she thought it ludicrous to have us write a test on this day of all days and intimated that she should have a word with our absent teacher to explain our poor marks. Finally, the test done, we were released out into the persistent rain of that cold grey day. While we all got thoroughly soaked, it did not matter. The Grade Seven class had worked on a long paper banner which they asked us to help them hold. We all excitedly looked westward toward the Village. A ripple of excitement went through the hundreds that had gathered as the procession was sighted. The banner, hopelessly soaked and torn, was forgotten in a sodden heap. We raced to our allotment beside the driveway to shout, scream, clap, jump and jabber excitedly as Rick Hansen wheeled his way onto the temporary stage that had been set up. Presentations were made; a few speeches (only partially audible above the din) said; and another banner signed. It was wet; it was cold; but none of that mattered. It probably only lasted a few minutes and was over, but Central had, if only in a small way, played a part in Rick Hansen’s global journey, his quest to raise money for spinal cord research. SOURCE: Dr. Greg Stott memories, 2008

The Watford and communities were not going to take such decisions lying down, and organized for a fight. Legal challenges were mounted and a concerted campaign to reverse, stall, or influence the decision-making process was launched. The main focus was a group calling themselves “Save/Support Our Schools,” or “S.O.S.” for short. Students themselves became involved in the process, expressing their concerns and sorrow over the impending closures. Over and over again, those who opposed the school closures admitted that, while the high school and the two elementary schools may have had their shortcomings in terms of facilities and students numbers, they were integral parts of their communities and vital for students, families and the larger social fabric. Groups received at least tacit approval for a moratorium on the school closures from the opposition Liberals in Toronto.74