From Forest to Field (Early Years)

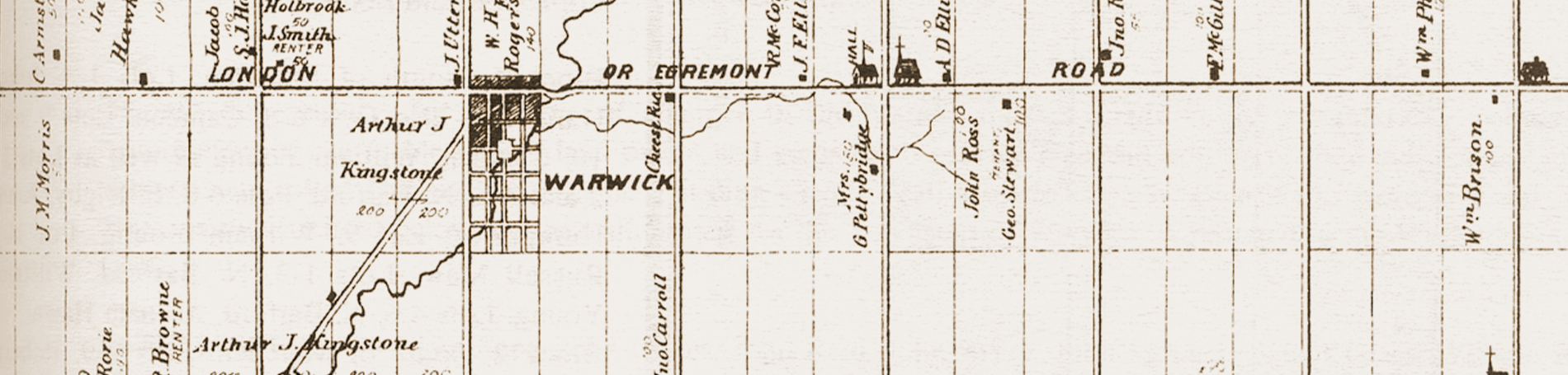

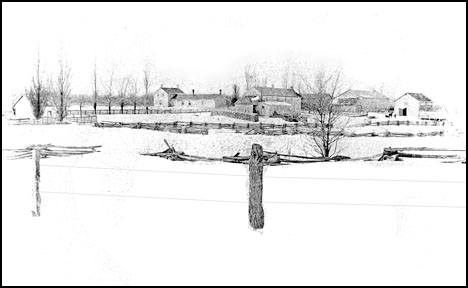

Pen and ink drawing of Carl Bryson farm on Arkona Rd.: The drawing shows a number of outbuildings, rail fences and the old brick cheese house that is still standing. Courtesy L Bryson.

by Glenn Stott

With Warwick Twp. having been seasonally occupied by natives for at least twelve thousand years, the coming of Europeans was simply another phase of the settlement of southwestern Ontario. When Upper Canada was created in 1792, southwestern Ontario consisted of nineteen counties. One of these was Hesse. Hesse was renamed the Western District, which included Essex and Kent Counties, the latter of which also included what is now Lambton County.1

The land which Warwick Twp. occupies was purchased in 1822 by Treaty #25 from the people of the Algonquin Cultural Group. The entire purchase consisted of 580,000 acres north of the Thames River, including the lands of present-day , Brooke and Enniskillen Twps. For this the natives received “2 pounds, 10 shillings each man, woman and child during their lifetimes and their posterity forever providing that the number of annuitants should not at anytime exceed 240 – being the number occupying the said tract of land.”2 The land was almost entirely forested with trees of the Carolinean Forest type, mainly maple, ash, oak, walnut, beech, and cherry. There would have been a few areas of clearing or secondary growth which marked the former areas of occupation of the Woodland Natives who, by 1600, had largely abandoned the area. In the early 1700s nomadic bands of Algonquin natives would have visited the area, either for seasonal fishing/hunting camps or while passing through on their way to trade their furs and other items with the European settlements along the lakes.3

The establishment of Warwick Twp. as a settlement occurred because of the necessity for the British government to find places for the thousands of ex-soldiers and their families who, following the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, were discharged into the English, Scottish and Irish societies. These were already facing serious stress from industrialization, major unemployment, political, religious and social difficulties.4 The circumstances in Great Britain were desperate, and the vast unoccupied wilderness of Canada was looked upon as a solution to these problems.

Canada, with substantial British assistance, had withstood an American attempt to conquer it during the War of 1812–1814.For the most part Lambton County was not a battlefront during the war: the natives who lived in the area went about their seasonal activities of hunting, fishing, farming and winter camping without much interference. Notwithstanding this, according to their tradition, many of the natives of the area were actively involved in assisting the British in their fight against the American invasion. Indeed, many of the ancestors of present-day native groups within Lambton County took part in some of the major conflicts of the war, including the capture of Detroit in August 1812, as well as the River Raisin battle in January 1813, the Fort Meigs battle in May 1813, and the battle of Moraviantown in October 1813. After the Treaty of Ghent in December 1814, these natives returned to their areas of settlement within Lambton County and received very little material recognition for their efforts by either the British or the Canadians.

Following the Napoleonic Wars, many of the officials of the British Army were selected to represent the King in positions of key responsibility. Men such as Colborne, Maitland and Richmond, whose names were synonymous with the defeat of Napoleon, came to Canada to exert their leadership in British North America.

The threat of another invasion from the United States in the 1830s was a stark reality from the point of view of the government of Upper Canada. Sir John Colborne, the Lieutenant Governor and a veteran of the Napoleonic War, foresaw the need for better roads and communication if Canada was to stand a chance in another conflict with America. At the same time, Great Britain was spending a fortune building fortresses for the defense of British North America with the construction of the citadels at Halifax, Quebec City, and Kingston. As an overall part of this project, major roads were planned to open communication with all border areas to provide better movement of troops to and from the potential areas of conflict.The government of Upper Canada planned to build a number of roads throughout the colony.

One of the roads planned was to connect the western edge of the London District (Middlesex County) with the Lake Huron port of Errol. In 1831 the surveyor, Peter Carroll from Beachville in Oxford County, was hired to survey and construct this road through the trackless wilderness of present day Adelaide, and Plympton Twps.5 The road was later named the Egremont Road after Lord Egremont, the benefactor of the Petworth Immigrants, although Colonel Talbot had wished that the road be named William the Fourth Road. According to Jean Elford, Sir John Colborne was responsible for the naming of Twp. after the Earl of , who was helpful to him in obtaining his first commission in the British Army.6

Lord Egremont George O’Brien Wyndham (1751–1837) succeeded to his father’s title as the 3rd Earl of Egremont in 1763. He was famous as a patron of arts and was a prominent figure in English society. Lord Egremont’s residence was Petworth House, Sussex. As a direct descendant of Sir John Wyndham he inherited estates at Petworth, Egremont and Leconfield, land in Wiltshire and Somersetshire, and also land in Ireland. The Earl was a sponsor of the 1832 Petworth Emigration Scheme intended to relieve rural poverty in England. He agreed to pay the travel expenses of any persons on his lands who wished to emigrate. The Egremont Road, envisioned as a military road by Sir John Colborne and surveyed by Peter Carroll, was named for the 3rd Earl of Egremont by the Petworth settlers in Lambton County. SOURCE: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Wyndham %2C_3rd_Earl_of_Egremont

This period in Upper Canada was very significant. Great Britain was looking to send thousands of emigrants to British North America; at the same time Upper Canada, a mere wilderness colony with very few financial resources and a very primitive infrastructure, was challenged to meet these needs. The government of Upper Canada was facing the costs of a massive influx of immigrants who had few personal resources to face the wilderness and the harsh North American climate, and who lacked the money to meet the enormous costs of surveying townships, clearing roads and building the necessary infrastructure required to make everything relatively functional. Upper Canada’s resources and finances were put under severe strain.

During the summer of 1831, Carroll and his crew of surveyors, axe men, and porters mapped and blazed a trail from the northwest corner of Caradoc all the way through to the Lake Huron shoreline. At the same time, Carroll surveyed the first two or three concessions on either side of the Egremont Road. Both Adelaide and Twps. were laid out with the Egremont Road being the centre of the survey and concessions were numbered as being south or north of the Egremont Road. Plympton Twp., which had the Egremont Road forming its southern boundary, was numbered in the traditional way, with the Egremont Road being the baseline.

In his book Pioneer Travel, Edwin Guillet outlines the procedure that was followed by the road crew. First an explorer would proceed along the route, closely followed by two surveyors with compasses. The boundaries of the roadway would be marked with blazes notched in the trees. Woodsmen would chop down all the trees lying within the boundary of the road along the course of the roadway. Next would come gangs of men whose job was to clear away the trunks and brush wood lying on the roadway. The whole crew was followed by the provision wagon which would bring up the rear.7 It was quite usual for these crews to leave the roadway with stumps two or three feet high remaining. These stumps would often remain until they rotted away, unless one of the property owners tried to have them removed.8

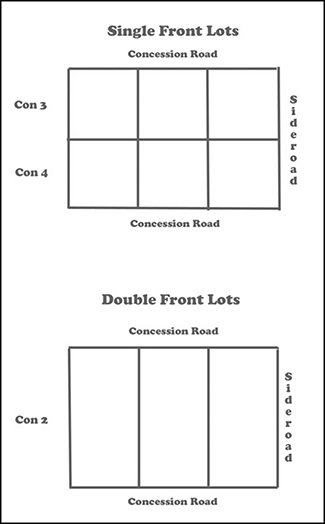

Single and double front lot surveys: All lots in Warwick Twp. are single front, while in Dawn Twp. the survey is double front, which means that a Concession road runs at both ends of the property. Th ere are two exceptions in Warwick Twp.: Lots 2-12 on Concessions 3 and 4 (Chalk Line) are double front, as are Lots 19-21 on Concessions 5 and 6 (Tamarack Line). Courtesy P Janes.

The narrow road was not very impressive, but the government of Upper Canada was desperate to get the huge numbers of immigrants who were crowding the ports to the frontier to look for new land.9 As a result, under the leadership of Roswell Mount, who was the postmaster of Delaware and also Crown Land Agent for the region, immigrants and settlers were hired to help clear the road for the coming onrush of settlement.10 By the end of 1832, the survey was complete and the lots were mapped out. Carroll, in the custom of the time, marked out the lots with a tree blaze at the corner of each property.

The survey of the entire township carried out by Peter Carroll in 1832 used a more up-to-date format for the survey, in that the concessions were laid out in a single front, unlike the earliest surveys which had the concessions fronting on two roadways.11 This meant that the lots and concessions were perpendicular to the concession roads. One concession backed onto another concession, meaning the lots of each concession fronted on only one concession road. The sideroads were located between every three concession lots and ran perpendicular to the concession roads. They were given the names after the lot they ran beside, for example, 12 Sideroad or 15 Sideroad.12 The roadways were 1 chain wide, or 66 feet, and the lots were laid out in 200-acre parcels unless it was an irregularly-formed lot, often called a “glebe,” affected by a boundary with another township or a creek or other prominent feature.

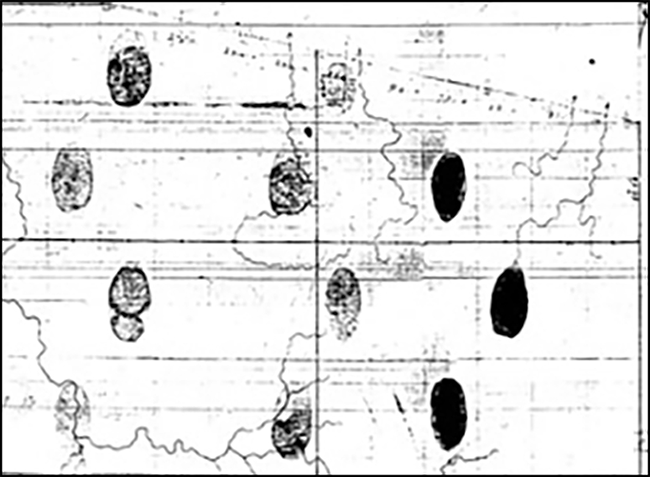

One-seventh of the township was laid out as Crown or Clergy Reserves, land set aside for use for government or church purposes such as schools, offices, barracks, churches or rectories. This was a serious bone of contention in other parts of the colony, leading to a great deal of unrest by the population, since neither the government nor the church was expected to complete the necessary settlement duties to obtain title to these lands. These lots were eventually sold off, as Crown and Clergy Reserves were no longer a viable option with land demands outstripping available land. On the original survey map of the Reserves were marked as brush strokes and their location appeared to be arbitrarily set. As a result, a settler with poor luck could find himself located between two Reserve properties, which meant no one was responsible for clearing any land or any roadways, which in turn would mean considerable hardship with wild animals, poor transportation for his goods and extreme isolation from his neighbours.13 This would become one of the issues facing the government of Upper Canada during the 1837–1838 Rebellion. It was, however, not a major issue in Twp., because most of the citizens had not completed all of their settlement duties before the “Reserve” system was abolished, and also because they were loyal to the Crown. Indeed, many of the men served with the militia and were assigned to protect the border at Port Sarnia.14

Settlers came flooding into the area very shortly after the survey was completed.15 According to the 1878 Lambton Atlas, the first settlers of were James and Robert Hume and their families, who came in 1832 from Carleton County near the Ottawa River to settle on Lots 25 and 23, Con. 2 SER respectively. Robert Hume’s daughter Betsey, whose mother is not identified, was the first white female child born in Twp. They were joined in March 1833 by another brother, John, who stayed with them until settling on Lot 27, Con. 4 SER in October. The Humes, according to the Atlas, had to travel for “years” all the way to Delaware, a distance of 36 miles, to obtain their provisions. Their homes also served as stop- over places for other settlers arriving in the area.16

According to one historian, ’s population at the end of 1833 was 852 persons with 1,166 acres cleared.17

Roswell Mount, as Crown Land Agent for the region, faced the prospect of 4000 immigrants arriving in the area in 1832. He recognized that these settlers for the most part were unprepared for the ordeals they would face during the year without having any trees cleared or crops planted. Using the limited resources provided him by the government of Upper Canada he constructed 250 log homes, measuring 16 feet by 16 feet, on each of 250 lots, to provide immediate shelter for many of the newcomers. The cost was over 900 pounds sterling, a considerable expense on a limited government budget, but Mount rationalized it as either assisting them or watching them perish.18

Even with this foresight, the hardships suffered by the very first settlers were terrible. Even the likes of Thomas Talbot, the founder of the Talbot Settlement or present- day Elgin County, felt sympathy for the plight of the totally unprepared people who came to Upper Canada lacking in the skills and knowledge necessary to survive the harsh weather, the harsh living conditions, the horrendous amount of work required and the total isolation of living in the bush.

Anna Jameson, a gentlewoman who travelled around Upper Canada in the 1830s, gives us a picture of what the settlers’ clearings would have looked like in Twp., although she was actually describing one she found in the Thames River region of present-day Kent County.

Thumbprint map showing Clergy and Crown Reserves, Warwick Twp., c. 1832: Th is is a portion of the northeast quadrant of the township.

As we neared the limits of the forest some new clearings broke in upon the solemn twilight monotony of our path: the aspect of these was almost uniform presenting an opening of felled trees of about an acre or two; the commencement of a log house; a patch of ground surrounded by a snake- fence enclosing the first crop of wheat, and perhaps a little Indian corn; great heaps of timber trees and brushwood laid together and burning; a couple of oxen draggin’ along another enormous trunk to add to the pile. These were the general features of the picture, framed in as it were, by the dark mysterious woods.19

In a letter written to Peter Robinson, Commissioner of Crown Lands and Surveyor-General of the Woods, on April 20, 1836, Charles Nixon, who became ’s first clerk in 1850, complains about being hired to construct a road during the summer of 1835 but not yet having been paid.20 He pleaded with Robinson that the pay for road work represented the only source of income available for “a number of us poor settlers who have no other means to procure the necessities of life for ourselves and families….” Nixon also stated, “Our township is very little better than a Wilderness yet for want of a mill to ground the little grain that we have raised so that provision is dear and the roads nearly impassable.”21 Robinson soon issued the funds to Nixon.

To add to the miseries of the settlers, the crops of 1835 were ruined by an excess of rain during the growing season. As a result, the grain produced could be used as livestock feed but was quite unsuitable for bread,22 although the grain not used to feed livestock could be sold to the nearest whisky distillery located at Kilworth in Delaware Twp. Until the farmers of had mills to grind their grain for flour a few years later, many had to go as far as Westminster Twp. near London to get it ground.23

A report written in 1840 by the Crown Land Agent for the Western District, Thomas Speers, clearly identified the difficulties facing the first settlers arriving in the Adelaide and areas. He mentioned that the settlers arriving at Kettle Creek in the summer and autumn of 1832 were hurriedly sent on their way due to the outbreak of cholera, “the scourge of the human race,” which was rampant in London, Upper Canada and other towns in the colony. Due to this rapid distribution, the new immigrants were not fully prepared and as a result suffered “incredible hardships.”24

| Lot | Con. | Acres | Locatee | Occupant | Acres |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SER (South of the Egremont Road) | |||||

| w1/2 10 | 100 | Chas. Nixon | -cropped by Nixon who keeps a tavern on main road | 12 | |

| e1/2 10 | 100 | John Head | nil | 1 | |

| w1/2 13 | 100 | Edward Bulger | Widow Bulger & Sons | 40 | |

| w1/2 14 | 100 | William Wellwood | nil | nil | |

| w1/2 18 | 100 | Wm. McCallaghan | nil | nil | |

| e1/2 18 | 100 | John McCallaghan | nil | nil | |

| w1/2 22 | 100 | George Henderson | nil | nil | |

| e1/2 22 | 100 | John Hand | nil | nil | |

| 23 | 100[?] | Robert Hume | occupies | 10 | |

| 3SER | |||||

| w1/2 12 | 100 | John Liddy | nil | 3 | |

| e1/2 12 | 100 | John Morrow | occupies | 7 | |

| e1/2 13 | 100 | James Lee | nil | nil | |

| w1/2 14 | 100 | John Callaghan | nil | 2 | |

| w1/2 18 | 100 | Darrel Kenny | occupies | 30 | |

| w1/2 19 | 100 | Ed’wd Mcnanainy | nil | 5 | |

| w1/2 20 | 100 | Anthony Garoin | nil | nil | |

| w1/2 22 | 100 | John Pratt | nil | nil | |

| e1/2 22 | 100 | John Webb | nil | nil | |

| w1/2 23 | 100 | Joseph Kennet | nil | nil | |

| w1/2 24 | 100 | Michael Gallagher | nil | nil | |

| e1/2 24 | 100 | Owen Morrow | nil | nil | |

| 28 | 200 | John Wellshead | nil | nil | |

| 4SER | |||||

| 16 | 200 | Arthur Barnstaple | nil | nil | |

| w1/2 28 | 100 | Jno. Donnelly Jr. | occupies | 16 | |

| e1/2 28 | 100 | Jno. Donnelly Sr. | occupies | 20 | |

| e1/2 29 | 100 | Wm. Crone (emg’t) | nil | 5 | |

| 5SER | |||||

| 5 | 200 | Arthur Barnstaple | nil | nil | |

| 28 | 200 | Arthur Wellshead | nil | nil | |

| 2NER | |||||

| w1/2 24 | 100 | Andrew Smith | nil | nil | |

| e1/2 24 | 100 | Or 4603 | |||

| e1/2 26 | 100 | John Brown | nil | nil | |

| 3NER | |||||

| e1/2 13 | 100 | John Pierce | nil | nil | |

|

w1/2 14 |

100 | John Sikes | nil |

1 cl’d, 4 chop’d 8 now into brush |

|

| w1/2 15 | 100 | Rich’d Evans Sr. | occupies | 14 | |

| e1/2 15 | 100 | Nicholas Evans Jr. | occupies | 6 | |

| w1/2 17 | 100 | Enoch Thomas | occupies | 30 | |

| e1/2 17 | 100 | John Thomas | occupies | 10 | |

| w1/2 18 | 100 | William Smith | occupies | 8 | |

| w1/2 19 | 100 | Andrew Thompson | occupies | 18 | |

| e1/2 19 | 100 | Duncan Dunlop | occupies | 6 | |

| e1/2 21 | 100 | Henry Cable | occupies | 14 | |

| w1/2 23 | 100 | John Fenner | occupies | 6 | |

| 6NER | |||||

| w1/2 13 | 100 |

James McIlmurray

|

10 |

SOURCE: Archives of Ontario [RG 1-605-0-3 Box 1]

Speers mentioned that the late Roswell Mount,25 then in charge of the district, hired many of the men to work at clearing roads, to provide them with some income with which they could manage to buy supplies. Speers lamented that this project was a “wasted exercise” due to the fact that the men hired were “unthinking men” who were “physically unable to complete a day’s work.” He also commented on the labour of the wives and children as being “precarious subsistence [as] they themselves [were] inadequate to any useful exertion whatever.”26

From his tone, Speers, at first light, appeared to hold a negative attitude toward the settlers. However, he was far from that. He railed against complaints by Robert Johnston, a member of a group who provided aid to these stricken people, who complained that “no regular account of receipts or their application [had] been furnished for the satisfaction of the subscribers [patrons of the society]” for their donations of money, provisions and seed wheat. Speers noted that when the settlers went to their lands after working on the roads, they had no employment for money or provisions and that some members of their family had died from absolute starvation during their absence. He referred to them as “unfortunate people” whose “toils, hardships, and extremes of hunger which no persons but as eye witness could have thought possible for human nature to endure.”27

Speers identified some of the errors which these settlers made when they first arrived. He claimed they took up land without thinking of how they would pay for it, even at 50 cents an acre. He felt the settlers saw the land as “El Dorado” but that it would lead to their ruin. He claimed many entered into agreements as if land purchase was a “free grant,” and that as a result many faced ruin. At the same time Speers noted that these men were loyal to the government and “cannot be surpassed and in a few sections of the country can’t be equalled.” He then asked that the settlers, who had been declared indigent, be sold their land at 5 shillings per acre to encourage settlement and loyalty.28

Dwelling among the first settlers in Twp., even though the land technically no longer belonged to them, were the people of the First Nations. They still carried out their hunting, gathering and fishing while was being re-inhabited by the white settlers. The natives lived in seasonal camps along the creeks where the women gathered fruit, nuts, and other items to be used for their sustenance. Men would fish and hunt and, when they had harvested all they needed, they would leave for another location. The early settlers, especially the family of Harry Alison, became quite used to the visitors who were always in the area.

John Holbrook, whose parents originally settled in Brooke Twp., stated that the natives would arrive at the back door with venison to trade for “salt pork.”29 He recalled going back to the creek one day and seeing a native woman sitting by a tent sewing beads on a moccasin. Soon a native hunter arrived, carrying a deer which he had killed. The couple invited John into their tent and inside he described it as the “very nicest place I’d every seen.”30

In her book, Jean Elford claims that by the mid 1840s game started becoming scarce due to pleasure hunting by both settlers and natives, in addition to severe weather. By that time, the number of wild turkeys, deer and passenger pigeons was markedly reduced in .31

The groups of settlers crowding into Upper Canada were of four distinct groups, all of which were represented in the earliest settlement of . First was the group which consisted of wealthy landed individuals who came from England, Ireland, or Scotland with the idea of purchasing land and setting up an estate in the new land. One such individual in was Arthur J. Kingstone, who purchased a large block of 1,600 acres in 1833. Captain R. Johnston of Delaware, in writing to Sir John Colborne, Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, on September 2, 1833, made a terse comment after praising the efforts of the stalwart leaders of Upper Canada such as Thomas Talbot, Mahlon Burwell and Roswell Mount, who provided “influence and example” to the settlers: “There are also several of our settlers who affect the Rank and consequence of Gentlemen who have withheld themselves from all subscription with a niggard hand.”32 Johnston also commented that these individuals did not make the success of settlement “insuperable.”33

The second group consisted of former soldiers who used their pension money to buy land in Canada to get a new start. Some of these were half-pay officers who were better off financially than regular private soldiers. It was this group of individuals who initiated the settlements of Napier in Metcalfe Twp., Adelaide Village in Adelaide Twp. and Village in Twp. Most of these men had spent their adult lives in the British army and, although accustomed to physical labour and hardships, were seldom given opportunities to show the initiative and decision-making that was required for pioneering in a North American wilderness. These “retired” soldiers were granted 200 acres each for their service to the King. It was noted that ’s farms at the outset were among the largest in the region, due to the large number of former soldiers who settled in the township. However, many of the men and women, after attempting to farm, ended up going to the towns and villages and taking up labour positions. Among those receiving grants were the Freear, Rivers, Fair, Luckham, Dunlop, Henderson and Lewis families.34

Timothy Gavigan, in his reminiscences of the early settlement days, reflected upon how his father was so ill- suited to farming:

My father didn’t know the first thing about farming in Ireland or anywhere else. He was a tailor in the old country and he made clothes here, too. Those days the farmers’ wives all made their own full cloth, took the wool to the mill and got it carded, spun it themselves and, when it was all spun, they sent it to the weaver or maybe wove it themselves, got it fulled and pressed at the mill again and then brought it to our place for father to make into suits.35

Many soldiers, such as Harry Alison, a former Captain of the 90th Regiment, were not cut out to be farmers, but managed to carve out a living using the resources of their family and the cash provided by their Army pensions.36

Harry Alison Captain Harry Alison (1775–1867) was brought up by an uncle and educated in private schools in Scotland. Having completed his education, he chose to join the 93rd Highlanders, where he received the rank of Captain and served as paymaster for over 30 years. While posted in Ireland in 1805 he married Frances Sinclair. From Ireland the Alisons were posted to the West Indies where both suffered yellow fever. Later he was sent to Corfu. Then, at the start of the War of 1812, he was ordered to Canada West. Captain Alison then commuted his pension, receiving a 1,000 acre grant in Canada West. The Alisons settled in the Wisbeach area of Twp. in 1833, on Lot 28, Con. 1 NER. They had 13 children, four of whom died in infancy. Their youngest was Peter John, who was six years old when they arrived. The Alisons’ son Rowland retired from the military at the same time as his father and received his own land in Canada West. Another son, Charles was appointed to the Embassy at Constantinople. A third son, Brisbain, who had joined the Navy but disappeared, then reappeared and moved to Canada with the family as well. One of their daughters, Frances Maria, married Thomas W. Rothwell. The Alison property was located on the highest spot in Twp. Mrs. Alison was known as Mrs. Wound Sewer for her knowledge of surgery and medicine and for her willingness to treat anyone who came to her door. SOURCE: newspaper articles and diary of Peter John Alison.

Colonel Arthur William Freear, who settled in Village, built a saw mill and was a more successful example of the “gentleman-officer class.” Freear, an officer in Wellington’s army at Waterloo, managed to maintain his property, and his family prospered even after his premature death by falling off a horse in 1844.37

Another former soldier, Duncan Dunlop, lost a leg during the Napoleonic War at the Battle of Toulouse, while serving with the 94th Regiment of Foot. When Dunlop arrived in Canada, he and his son, Duncan Jr., worked on the road crew hired by Peter Carroll to clear the land for the Egremont Road. When he had earned enough, he and his son settled in and farmed successfully.38

The third group of immigrants consisted of the offspring of United Empire Loyalists, who qualified for a land grant of at least 200 acres which they could claim in the newly opened lands in the Western District. Many of these individuals moved to from the eastern portion of Upper Canada such as Lanark and Carleton Counties because of more fertile land. These people had a background of farming and clearing trees and were familiar with the hardships of living in a wilderness township like . For the most part these individuals were able to adjust to the pioneer life of .

Among these families was the William Burwell family, United Empire Loyalists who settled on Lot 10, Con. 1 NER. Burwell built two buildings, one a cabin for his family, the other a tavern. Burwell’s family, being well-established in the routine of life in a wilderness, knew what to do to make a profitable existence in Upper Canada. Burwell’s son Elijah was the first white child recorded to be born in Township.39

He was able to wisely invest his funds to the best use and avoid costly mistakes. The tavern, which served as a hotel, was also used for public meetings, court, church and many other purposes, for it represented the only “public” building in for several years. The tavern attracted both travellers and local settlers.

John Jones, in his travel diary of 1834, stated that he “Breakfasted at Bear Creek, found a fidler [sic] at Burwell’s and danced French Fours and Eight Reels until midnight.”40

The fourth group consisted of impoverished immi- grants who had been unemployed and destitute in Great Britain. Charity groups such as Lord Egremont’s Petworth Society helped support them in their emigration to Upper Canada. The Lambton Atlas identifies some of these immigrants who settled in a specific area of northwestern that became known as the “English Settlement.” Eleanor Nielsen states that the sponsor of this group of settlers was not Egremont but the Honourable John Elmsley, who had sponsored five families from Wiltshire, England. He took these families to his “estate” called Clover Hill, located on Lots 3 and 4, Con. 4 NER, .41 The atlas goes on to identify some of the families in this group as Harvey, Maidman (or Maidment), Liddy, Moore, Reddick, Randall, Robinson and Whelems.

Some of these “inexperienced” settlers were able to obtain road work and earn some money for subsistence until they gained farming experience to survive. Most, however, had no idea of how to survive, let alone farm in the bush. Many abandoned their land and went to the towns or villages to work as labourers. Others struggled during the first years until there was a successful harvest, finding tender shoots, leaves, twigs and wild plants that could be made into an edible stew or “browse” for them to eat. One family, the Luckhams, had their oxen die and were forced to harness themselves to their homemade harrow to clear their land to plant the wheat.42

Among the applications for land during ’s first years were also a number of speculators who were looking at ownership of land as a means of either gaining or maintaining wealth. Among these individuals were Lord Mount Cashel, who at this time lived in Lobo Twp., and even the esteemed Bishop of York, John Strachan.43

Lord Egremont had a great deal of influence over affairs, even in distant Upper Canada. One story has his influence lead to the naming of and Brooke as he was Granville, Earl of and Brooke. As a result of his efforts to settle the Petworth Society immigrants, the two most affected townships may have been named after his English estates. Adelaide was named after King William IV’s wife.44

Cow Cabbage: In the early stages of the settlement of Twp., the settlers without any crops planted or food supplies readily available resorted to eating “browse” and “cow cabbage”. Dorothy Tiedje, a noted biologist with the Lambton Federation of Naturalists, went to work to fi nd out what cow cabbage may have been. She found two different descriptions. In an article entitled, “What is Cow Cabbage?” James Pringle of the Royal Botanical Gardens in Hamilton suggested that Skunk Cabbage may well have been the plant used by the early settlers. An alternate name for this plant is “Meadow Cabbage.” He stated that the leaves are edible when boiled, but he highly doubted that this plant would have been widely available throughout Ontario and it certainly was not eaten by cows. In the article he was inconclusive and called on readers to make suggestions. In another article some suggestions included Virginia Waterleaf and Canada Waterleaf which were often called Cow Cabbage in Bruce and Grey Counties. One of the more logical suggestions included the White Water Lily which was eaten by cows. It was noted that in the spring the leaves were boiled and eaten as greens. Whether Cow Cabbage is another word for Skunk Cabbage, or Virginia Waterleaf or White Water Lily, even modern botanists are not certain. Nevertheless the early settlers of used a plant known as cow cabbage to survive. SOURCES: Field Botanists of Ontario, FOB Newsletter, Spring, 1996, Vol. 9(1), p. 7 Ibid, FOB Newsletter-Winter, 1996/7, Vol. 9 (4), p. 9, and C. Erichsen-Brown, Use of Plants For the Past 500 Years, 1979, p. 210.

The usual route of travel for all groups of immigrants was by lake schooner to Port Stanley (Kettle Creek) or Port Glasgow. There they would disembark and travel inland by wagon to one of the camps or depots established by Crown Lands Agent Roswell Mount; these were located in the Delaware and Caradoc Twp. area, as well as in Metcalfe Twp. which was then known as “Branan’s Settlement” or Katesville.45

From there, they would follow guides hired by Mount along the bush roads to , using the Egremont Rd. as their east-west route. They would be taken to a vacant lot, where a log cabin had been built for their shelter, and would there begin their new lives in.46

The struggle of these settlers left a lasting impression on the travelers, government officials and missionaries who visited the area. One missionary reported in the Christian Guardian in 1842, “The people [of Twp.] are chiefly English and very poor. I have seen some mothers of families come out in winter to hear preaching with their feet rolled up in rags….”47

In this way, Mount, faced with an influx of what he stated was 4,000 immigrants, was able to place all of them successfully, although he noted that only half of the immigrants in his care were able to find work or become self-sufficient without any assistance from him and his agents.48

The stories of these European immigrants and their early settlement of would fill volumes. The landed gentry were able to hire work done by the countless labourers in the settlements. Manual labourers tried to save enough money to purchase their own land, or simply to survive. Thomas Radcliff, who settled on his estate in Adelaide in 1832, described some of these labourers as men who duped the unknowing settler who hired them into either doing most of the work himself or being fleeced of his hard-earned cash through a variety of means.49

The settlers, in order to complete their settlement duties, had to clear a certain portion of land within a specified period of time before they could receive a “patent” or title to the land. Methods of clearing large acreages of land varied. Reverend Thomas Radcliff, of neighbouring Adelaide Twp., described one of the more common methods.

He noted that the best method of cutting down large trees was to cut each tree separately, making it easy to cut the tree into 12 foot lengths. If longer, the logs needed more than one yoke of oxen to draw them to the pile where they were to be consumed. The brush would be placed into huge piles to be burned. Young settlers were frequently imposed upon by cunning choppers by not adhering to these guides. The choppers could thus save themselves work and also make more money for their employer.50

Thomas Radcliff was one of the hundreds of half- pay officers who settled in the Adelaide, and Plympton area following the completed survey and the marking out of the Egremont Rd. at the end of 1831. He, and others like him who had some income, were more apt to hire individuals who would do their work. The majority of the settlers, who came with fewer financial resources, had to do most of the work themselves or with the assistance of their neighbours in working or logging bees.

Peter Alison, a son of a retired officer who located on Lots 28 and 29, Con. 1 NER, recorded in his journal that neighbours would spend the winter chopping trees down in the bush. They then removed the tops and trimmed the logs which neighbours would store for a logging bee on a specified day. When the day approached, settlers from all around would come early in the morning with their oxen teams to assist in the hauling of the logs into huge piles which would then be burned. The women would also come to prepare a huge noon meal for the workers. Following the day-long toil, Alison reported that men and women would produce more food, drink and a fiddle and “a jolly night was sure to follow.” The party often would not stop until the morning hours.51

The dangers facing the earliest settlers of were countless. Accidents from everyday activities, although minor in nature, could lead to major complications due to the isolation of the township from the more civilized regions of London and the Western District. Possibilities for more serious injury or even death were frequent.

In 1832 to 1834 a cholera epidemic struck hundreds of people in larger communities, including London. , because of its isolated situation, was spared this difficulty.

Archibald Gardner, who settled in 1835 on 500 acres in the southern portion of using his “soldier’s rights” at 50 cents per acre, was working two and a half miles into the bush on his lot from where he stayed at night. One afternoon he split his foot with an axe and had to hobble back to his lodging to get help and have the foot bound. When he arrived there, he found it completely deserted. He crawled another mile and a half to a “nearby” shanty, where he found a man and woman living. They assisted him but the next morning the man of the house left to get provisions, leaving Gardner on his own. Gardner spent a total of seventeen days incapacitated.52

In his journal, Peter Alison tells the story of a “murder” which went unpunished:

All was now in a state of commotion and every man that was able to bear arms in the country was sent off to fight the rebels [in the 1837–1838 Upper Canadian Rebellion]. A few old men that had families were left to cut wood and attend to the stock of their neighbours and the one that had to attend to our colony was not a pleasant fellow to look at. When talking to him, he never could look you straight in the face. His weasel eyes would shift about in all directions as if he were afraid you would find out something criminal about him and I believe he had good cause to feel uneasy, for sometime before this an old man, who lived in a shanty by himself and was supposed to have money, was found dead by a log of wood that he had been chopping in front of his door, and our worthy attendant was strongly suspected of having murdered him, as he got well off very rapidly afterwards.

A kind of inquest was held, but as there was no one in authority within thirty miles of us, the matter was allowed to drop; but the Good Book tells us, “What a man soweth, he will surely reap” and so it turned out with our woodchopper. Whether it was that his wife knew about his evil deeds or not, no one could tell; but they could never agree. She appeared to take a thorough dislike to him and he did everything he could to make her life miserable. It was reported at one time that he tried to murder her, but as she never corroborated the report it died out like the murder he was accused of. She ultimately died of a broken heart, no doubt, for she had a wretched life with him. After her death, he went to Scotland where he was born and brought a woman back with him, whom he called his niece. She lived with him about a year, when a very strange thing happened. He encouraged a young farmer, who was already married but separated from his wife, to pay attentions to this girl. She received his attentions and they finally were married in the uncle’s house; but no sooner was the last word said that bound them together, when her uncle opened the door and ordered the new-made husband to be gone and never show his face near his house again. In a few days he bundled up her traps and went to the States, taking the new-made bride with him — for what purpose is not known.

No one ever knew, but shortly after we saw by the papers that he was crossing a river in a small boat when it upset and he was drowned. The new-made bride would no doubt have come in for a good share of her uncle’s property, if not all, had she had the courage to hold it; for immediately after her marriage he made it all over to her so as to cut his three children — a boy and two girls — out of it. “Man proposes and God disposes,” for the girls had married two smart young farmers, who, with the sons and the new-made bridegroom started off for the States as soon as they heard of the old man’s death; and so frightened the bride with law that she signed back all the property again. What became of her afterwards was never known. The property consisting of four hundred acres, two hundred of which were well stocked and had good farm buildings erected on them, was equally divided among his three children and they paid the new bridegroom a few hundred dollars to get rid of him. Thus ended the life of a very bad man. He reaped what he had sowed.53

Settlers learned to help each other in order to survive. During the summer of 1835, Archibald Gardner, after he recovered from his foot injury, decided to work with a neighbour, William McAlpin. They would exchange work with each other by working at one another’s farm sites. To save themselves the long trip back to a permanent shelter each night, they constructed a “rude tent” from branches and bark. They carried their provisions in a knapsack loaded with dry bread or crackers, a musket, and ammunition, which all together weighed forty pounds. Gardner and McAlpin existed on a porridge of flour and water, or cakes of flour and water cooked in a frying pan, and occasionally treated themselves with some bacon. They were used to walking great distances to get provisions.54

Early Days in Lambton: Around 1840 Duncan Park was walking from Watford to Wanstead to pay a visit to his brother William. He was using a pathway which was a well-defined Indian trail along the banks of Bear Creek. Along the trail, he met a young native couple who were travelling the opposite way, making their way to Munceytown. The couple was hauling their possessions in a hand sled which the male was pulling and the wife was pushing from behind whenever it got stuck. On top of the load was a loaded rifle with the muzzle pointing to the rear of the sled. Since they didn’t speak any English and Park did not understand their language, little communication took place. After they passed each other, the couple left the path and took a shortcut, a wagon trail that had been made in 1836 by the Anderson family when they moved to their Plympton homestead. After a few minutes Duncan heard what he thought was a gunshot behind him. He kept on. After a few days he returned with his brother, using the same route. As he walked, a little distance past where he had met the young couple days before, he came across a wigwam near the creek where it intersected with the -Plympton Townline. When he looked inside the wigwam, he saw the native woman lying inside with a horribly shattered leg, caused by the rifle which had accidently discharged. Duncan was unable to communicate with the distraught couple so he continued on his way. Eventually, word reached Munceytown and a native doctor arrived at the wigwam. Five or six weeks later, settlers from around Watford came to the door to see the wounded woman being removed on a bier of poles, basswood bark and blankets by a large group of natives who carried her, four at a time, to the Caradoc Indian Reserve. Word came back to Watford several months later that the woman had died of her wound. SOURCE: Sarnia Observer, May 21, 1886.

Alison recalled that money was often scarce and young men, including himself, would hire themselves out to others to earn some cash to assist the family. He describes one winter’s day when a man from Scotland dropped by their property on a long 40-mile trek to the St. Clair River to visit his family. He was exhausted and wished to hire someone to drive him the rest of the way. Alison’s father only had a horse but no cutter. A cutter was not to be had anywhere around. Peter, who was a gifted carpenter and assisted local settlers in repairing their farm implements, went into the bush that afternoon and cut down two ironwood trees. He set to work with his axe and auger and fashioned a “jumper” used by woodsmen to haul logs from the bush. In the morning, he hitched the horse to the jumper and pulled up in front of the cabin and announced he was ready to take “Sandy” to the St. Clair. The Scotsman replied “Well man, that beats all I ever saw in my life! If I don’t have something wonderful to tell when I get back to Scotland, it will not be your fault.” Peter and the Scotsman headed off to the St. Clair at an amazing clip of five miles per hour. Staying overnight, Peter returned late the next day with a five dollar bill to show for his efforts. He gave the money to his mother.55

Alison was also hired out as a chain man (who carried one end of the surveying chain and placed it according to the surveyor’s instructions) to the surveying crew who were building a road to Port Sarnia. Although small in size, he managed to do the work, which took six weeks to complete. At the end of the time he returned with $40 to add to the family’s supply.56

In the 1830s few communities could boast a doctor being available. Frequently, in times of illness or injury, settlers would rely upon the skills of a few individual people who became known for their nursing ability. Mrs. Alison was one of these few people in . Mrs. Alison had lived in numerous army camps with her husband during the Napoleonic Wars and as a result had become quite skilled at primitive first aid. She had learned how to mend wounds and prescribe remedies for a variety of illnesses. She became well known by the numerous natives of the region as “Mrs. Wound Sewer” not only for her skills but also because of her kindness.

One incident which quickly became part of Twp. folklore occurred on a cold wintry night in 1835 when the Alison family were in the midst of their evening meal. Through the door burst an Indian demanding food and a bed. When he approached the light from the candle it was seen that he was bleeding profusely from a gash in his head. He approached the table brandishing his knife and tomahawk yelling, “Food! Food!”

Mrs. Alison saw immediately that the man was very weak, and she got her boys to seize him and help him into a chair where they had to hold him down. Meanwhile, Mrs. Alison bathed the wound with soap and hot water. She found the wound wasn’t too deep but she had to shave the area, stitch it and cover it with a bandage. The men then laid the man down on a blanket on the floor by the fireplace where he fell into a deep sleep. In the morning, he was fed a hearty breakfast and without a word he left the cabin.57

Natives would come and sleep in her cabin during the night, but also from time to time seek medical treatment. Harry Alison would ensure that there were extra logs by the fire for them to warm themselves. Mrs. Alison would also make sure that they had warm clothing before they left. They would quickly depart but would return with gifts of moccasins, beaver pelts for a coat, fish, or venison. They also assisted her family in harvesting crops.58

It is reported that not only did the natives rely on Mrs. Alison for medical treatment, but the settlers soon came to rely on her as well. She was visited on a regular basis by the ill and infirm, and she made house visits if necessary. This she did without accepting a penny in payment: she simply said “I am just happy to be of some use in this world.”59

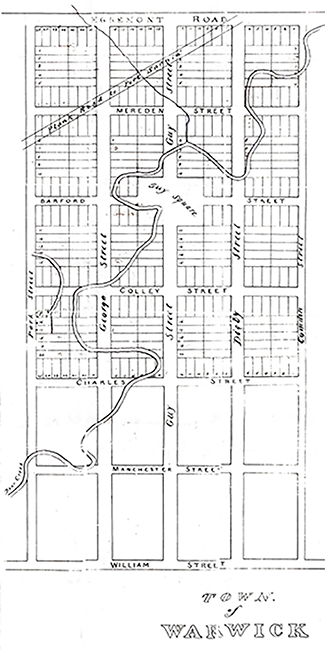

Warwick Village survey, c. 1834: Warwick Village was laid out as a town south of the Egremont Rd. Th is map also shows the Plank Rd. to Port Sarnia, established in 1846 to connect Warwick to Sarnia. Courtesy P Evans.

Wolves were one of the most feared dangers which faced settlers in . Modern study now shows that the threat of wolf attacks on humans, even in pioneer times, was very much a myth and indeed, although most settlers of would not be convinced, wolves seldom really presented any major danger of attacking a healthy person in the bush.60 For livestock, however, wolves were deadly. William Williamson described the wolves as “great big grizzly brutes” which preyed on livestock, especially sheep. The farmers had to keep their sheep locked up during the night for fear the wolves would attack the flock. Even then, Williamson said that one morning he found 14 dead sheep inside the barn. A wolf had managed to get into the barn and killed the entire flock. Williamson also claimed wolves would “worry” the cattle by chasing them in the field and biting at them.61

Peter Alison reported that most people were frightened of wolves because of their terrible howling during the night, but many knew that wolves were generally frightened of humans and would flee at the first sign.62 But stories of wolves were always told:

I remember one time, when returning home from a bee with my oxen about three o’clock in the morning, I was startled by the howl of a pack of wolves so close that I thought my hour was come. It was very dark and what made it still more terrible, I had about a mile of woods to go through before I reached our clearing. I do not know which made the greater noise — my heart beating or the wolves howling! I had heard that the rattle of anything trailing on the ground would keep them at a distance; so I let down the chain from the yoke and as I knew the oxen would keep the road in the dark better than I could, I mounted the near one and set them off in the full gallop and never stopped till I got inside our gate, when our faithful old dog came to meet me barking with all his might, which no doubt frightened them away, for I heard nothing more of them. The oxen, I think, were as much scared as I was, for they required no whip to urge them along. The wolf is a very cowardly animal and will never attack anything except he is sure to overcome it.63

Timothy Gavigan remembered wolves when he was a boy in :

I’ve seen dozens of wolves. When we boiled sap in the sugar bush you’d hear them howling all around. They wouldn’t come to the light where the fires were, but one pack would meet and howl on one side of the sap bucket and another pack on another side. You could see their shadows slinking away and hear their howls. We had to keep our pigs and lambs and sheep shut every night for fear of them being eaten by the wolves. Before the night we would drive them all into a shanty and fasten the door. Of course, it didn’t take much room, because we didn’t have many animals all told in those days.64

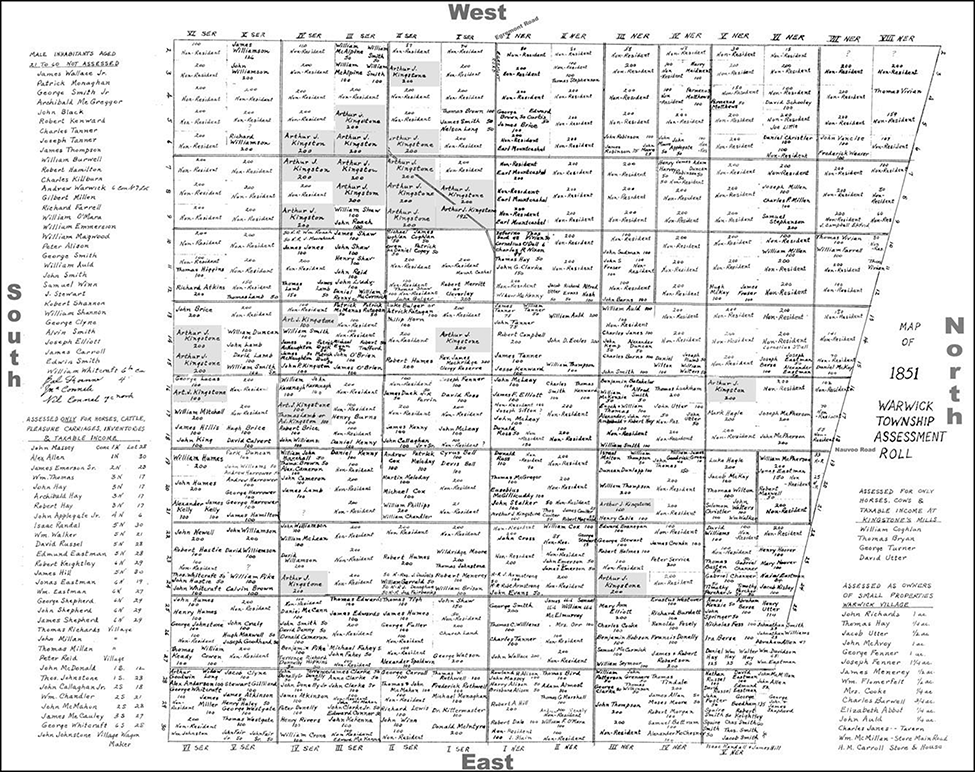

1851 census map: Th is map also shows the location of the Kingstone properties in grey (see chapter 4). Th is line called Egremont Road is the dividing line between SER & NER mentioned throughout the book. Courtesy D Fenner.

There are also reports of dangerous encounters with bears. Benjamin Williamson recorded his encounter with a bear as a seven-year-old boy heading home from school.

Well, this night it was summer time — about the first of July — I was just coming home from school when I happened to turn around and look into a little bit of a clearing, and I saw six or eight pigs running round and round and a big black fellow with a white nose going round the outside of them. Every time the black one would get close to the others they would start snorting. I was only seven or eight years old but I can remember thinking there was something funny about the way those pigs were acting. So I went over to the fence to get a better look. The black pig stood up on its hind legs and looked at me!

… I had never seen a bear before. I turned and ran for the house as fast as my legs would carry me…. I ran out again and down the hill behind the house where mother and dad were hoeing corn. “Dad, there’s a bear up there.”65

Williamson’s father went to the house and got his “old English musket” and went to the pig fence, but the bear had left. It returned that night and took one of the pigs. That, however, was the first and only time Benjamin saw a bear in .66

By 1834 elements of “civilization” were beginning to appear in . Colonel Freear had built a sawmill on the north branch of Bear Creek, on Lot 10, Con.1 NER. The government surveyed Lot 10, SER, as a village site for the future development of a community. By 1835, had 61 taxpayers living in the community, with 250 acres cultivated and livestock consisting of 4 horses, 24 oxen and 34 cows.67 Shortly after Thomas Hay established a blacksmith shop in

For all the settlers, the first years of settlement presented enormous challenges, especially considering that they were not used to the wilderness life. John Thomas recounted that his parents, who settled in in the early 1830s, were able to confront the challenges because of their strong spirit of adventure.68 When his father went to Sarnia to greet his new wife, they had to return to by walking the whole distance, as roads were poor and his father had neither oxen nor horse for transport. Thomas continues that for the first years all provisions had to be brought from London. His uncle, Enoch Thomas, was accustomed to carrying a 50 lb. bag of flour all the way from London.

was in the middle of the wilderness, isolated not only from the lakes and major rivers of the region, but also from larger settlements. The immigrants who chose to settle in had to suffer the hardships of wilderness life and the isolation compounded by poor roads and nonexistent infrastructure. As a result, the early years of represent incredibly difficult times not always common to the settlers of early Ontario. However, by the end of the first decade of European settlement was well on its way to becoming a prosperous, independent rural community with its own mills, churches, schools, hotels and businesses and a developing system of roads.

By 1850, the Township of , under the Municipal Act of 1850, had its first official municipal government, with Robert Campbell as Reeve and John Eccles, George Harrower, Robert Hill and William McAlpine as Councillors. Charles Nixon was the Clerk; John Williamson the Treasurer, and Enoch Thomas was the Tax Collector.69 It was no longer a wilderness, but a developing rural township made up of many small communities and farms.

Endnotes

These links were used at the time of publishing in 2008. Some links may have changed or may no longer be active.

1. Jean Turnbull Elford, Canada West’s Last Frontier: A History of Lambton, Lambton County Historical Society, 1982, p. 2.

3. Glenn Stott, Witness to History: Tales of Southwestern Ontario, 1985, p. 10.

4. Thomas Radcliff and J. J. Talman, ed., Authentic Letters from Upper Canada, Macmillan, 1953, pp. xi–xii. J. J. Talman explains the political, religious and social problems in Ireland which made a number of “landed gentry” leave Ireland.

5. Peter Carroll (1806–1876) was also responsible for the surveying and laying out of the village of Ingersoll in 1834. He attempted to enter politics in Oxford with little success. He moved to Hamilton in 1840 where he worked as a road contractor and served on the Board of Directors of the Great Western Railway. See Brian Dawe, Old Oxford is Wide Awake!, 1980, p. 48.

7. Edwin Guillet, Pioneer Travel, Ontario Publishing, 1939, p. 123.

9. Upper Canada State Papers, RG1 E3, p. 101, 105, &106. UWO Library, Reel C-1193.

10. W. Cameron, S. Haines, M. McDougall Maude, ed., English Emigrant Voices: Labourers’ Letters From Upper Canada in the 1830s, p. 411.

11. Tweedsmuir & Early File Notes. n.d. p. 6.

12. G. Herbert, G. Herbert Collection, n.d., n.p. If you wish to see examples of different formats of surveying consult the County of Lambton Atlas, pp. 70–71. The County of Lambton has only two townships with a double front survey, Sombra and Dawn. All the other townships have single front surveys.

14. 1837 Rebellion Pay Sheet, Feb. 1838, copied by Cliff Lucas, and Alma McLean, Lambton Room, Wyoming.

15. Eleanor Neilsen, The Egremont Road: Historic Route From Lobo to Lake Huron, Lambton Historical Society, 1992, p. 16. It was stated that 2442 alone came to Adelaide– in 1832.

16. Edward Phelps, ed., Belden’s Historical Atlas of Lambton County 1880, Phelps, p. 18.

17. Margaret Redmond, ’s First Twenty Years, unpublished manuscript, January 1996.

18. Eleanor Nielsen, The Egremont Road, pp. 14–15. See also “Roswell Mount”, Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, U of T, 2000.

20. Frederick Armstrong, Handbook of Upper Canadian Chronology, Dundurn, 1985, p. 43.

21. Upper Canada State Papers, Nixon to Robinson, April 20, 1836, pp. 107–108. Also Elford, p. 94.

24. Thomas Speers, Crown Lands Agents’ Record Concerning the settlement of Adelaide, Metcalfe & Townships, Chatham, June 30, 1840, PAO, RG1-605-0-4, p. 1.

28. Ibid., p. 4. Speers says that at the time of his writing, 1840, the settled areas were prospering and the settlers had excellent farms.

29. Lambton Settlers Series: Early Days in Brooke and , Vol. 3, Lambton County Branch of Ontario Genealogical Society, 1995, p. 23.

32. Capt. R. Johnston to Sir John Colborne, Sept. 2, 1833.

35. Lambton Settlers Series, Vol. 3, p. 16.

36. Memoir of Peter Alison, UWO Archives. Peter Alison states that his father Harry was a gardener, not a farmer. His father used up his financial resources establishing their home. He sold off 900 acres of his 1000-acre grant to pay for the expenses. When he passed away, he left two 50-acre parcels to his two sons.

37. Eleanor Nielsen, The Egremont Road, pp. 73–75.

38. Wib Dunlop, interview, May 2007. Duncan not only was one-legged, but also was widowed when he arrived in Upper Canada. He farmed, cleared the land, and raised his family by himself.

39. “ Village”, Tweedsmuir Book, Women’s Institute, p. 6.

41. Eleanor Nielsen, The Egremont Road, 1992, pp. 38–39.

43. Land Records, Lambton Room, Lambton County Building, Wyoming.

44. L. M. Stapleford, “Colborne as Governor Speeded Building of Watford District”, London Free Press, Sept. 28, 1946.

45. Jennifer Grainger, Vanished Villages of Middlesex, Natural Heritage, 2002, p. 167.

W.A. & C.L. Goodspeed, The History of the County of Middlesex, Mika, Belleville, 1972, p. 531.

46. W. Cameron, S. Haines, M. McDougall-Maude, ed., English Immigrant Voices: Labourers’ Letters from Upper Canada in the 1830’s, McGill-Queens University Press, 2000, p. 7. The editors state that the vast majority of the Pettworth Settlers were established on the 4th and 5th Concessions of Adelaide and only a minority were settled in .

49. Radcliff and Talman, p. 92.

50. Radcliff and Talman, p. 93.

51. Peter John Alison, memoirs, Western Archives UWO, B5582, p. 8. It is probable that Dr. Edmund Seaborn transcribed the journal from the original.

52. Wilfred W. Gardner, The Life of Archibald Gardner: Pioneer of Utah, Archibald Gardner Family Genealogical Association, West Jordan, Utah, 1939, p. 12.

57. Catherine James, “Indians had a Friend in Mrs. Wound Sewer when Trouble Brewed”, London Free Press, Jan. 18, 1964.

60. Death of a Legend, National Film Board, 1968.

61. Lambton Settlers Series, Vol. 4, p. 58.

64. Lambton Settlers Series, Vol. 3, p. 17.

65. Lambton Settlers Series, Vol. 4, pp. 51–52.

67. Women's Institute Tweedsmuir Books, Lambton County Library, Wyoming. These notes state that John Fair was the first assessor, in 1835. He was a former sergeant in the British Army and therefore was literate and able to do the tasks necessary. See also Elford, p. 94.

Subscribe to this page

Subscribe to this page