"A Disgraceful Riot"

The 1863 Race Riot in Oil Springs

"We regret to learn that a disgraceful riot took place at Oil Springs . . .

As in the shameful proceeding which occurred in Detroit was colourphobia.'

-- The Sarnia Observer, March 19, 1863

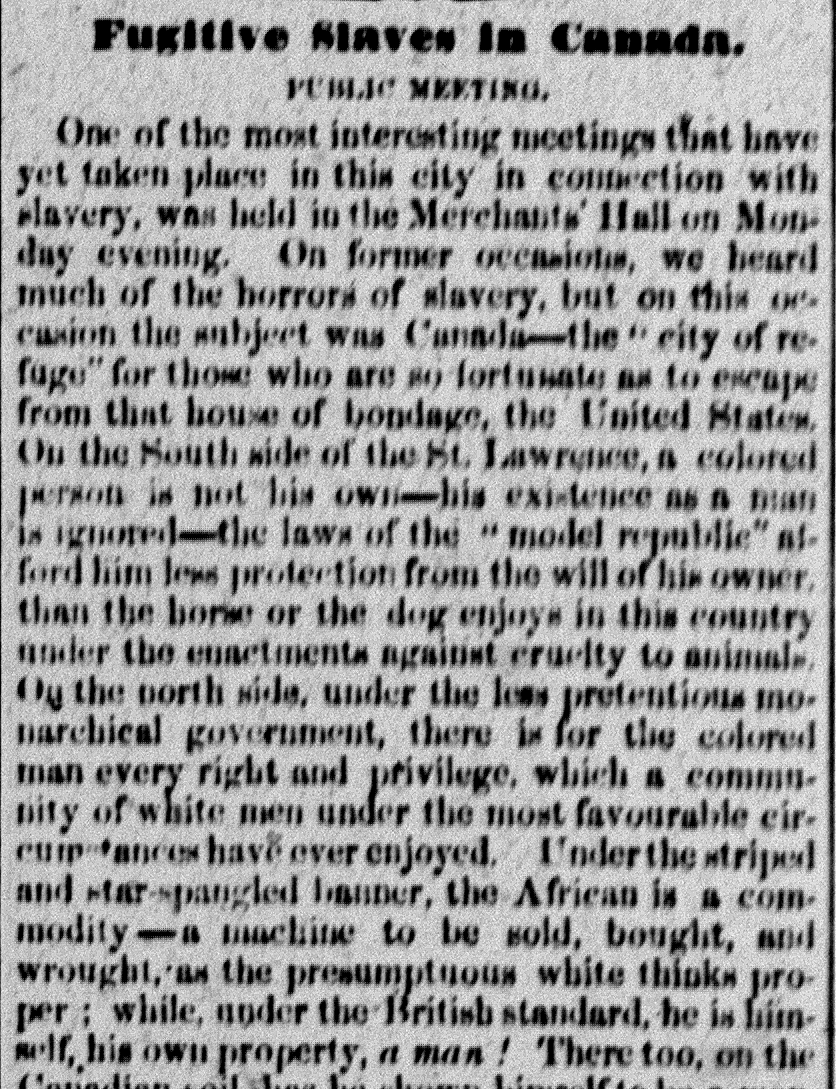

Canada had long framed itself as a more accepting place than its southern neighbour, the USA. Although Canada served as a haven from enslavement for Black people, things were not perfect. Racism ran deep and Black people faced discrimination and anger from many Canadians. The Oil Springs riot flew in the face of Canada’s own perceived neutrality and forced many to face the reality of Canadian racism.

Even so, as enslaved Black people escaped bondage via the Underground Railroad, many continued past the northern states into Canada. Freed-people also left the USA for Canada. Black settlements dotted Upper Canada (today Ontario) and Black populations grew in cities such as Windsor, London, Chatham, and Amherstburg. Most of these areas were "terminal points" of the Underground Railroad.

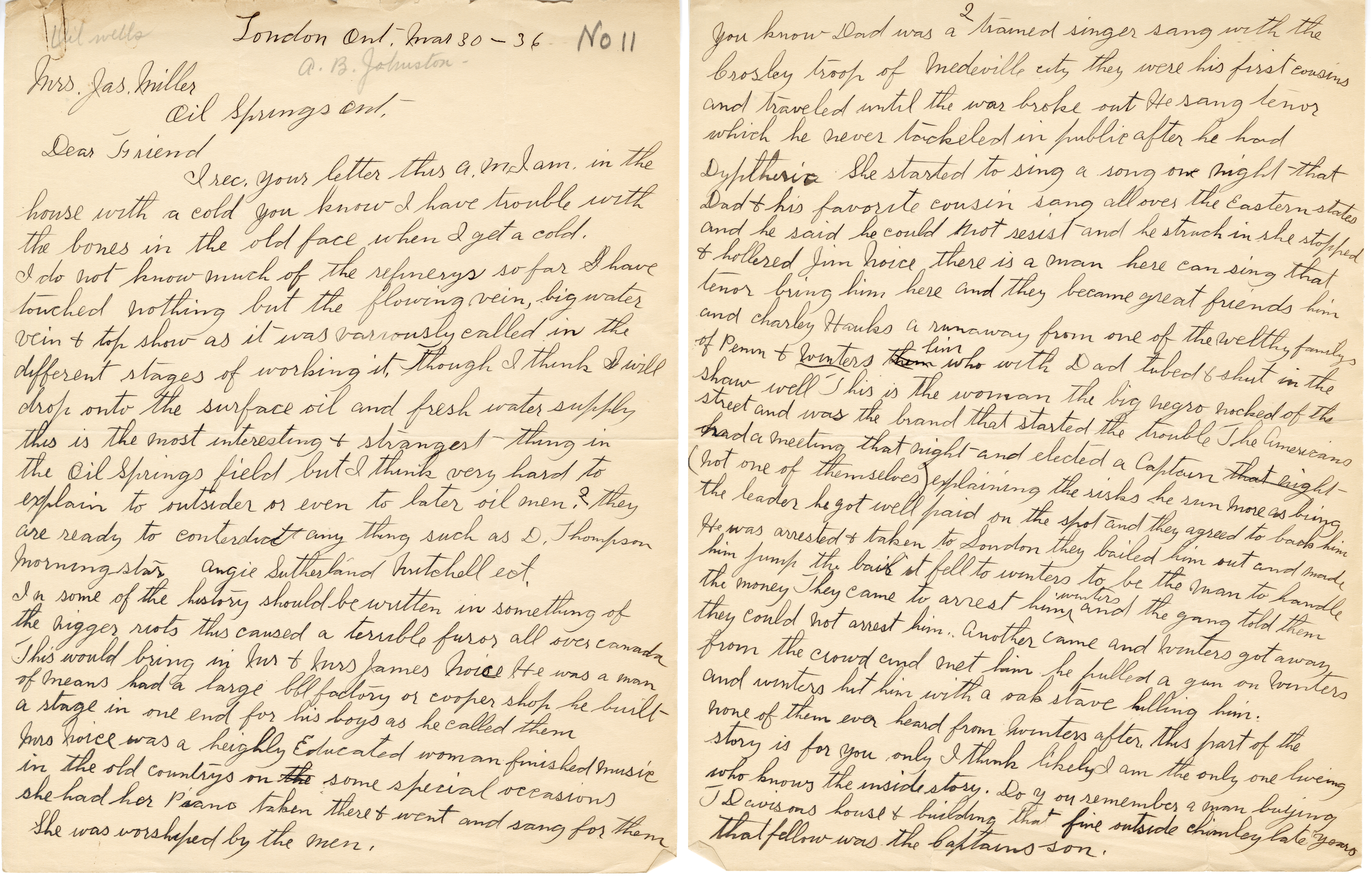

"Fugitive Slaves in Canada," Article from the

Sarnia Observer, February 6th, 1862.

Black Settlements and Underground Railroad Terminal Points, SW Ontario. Oil Springs is marked as a red star. Click on a point to see the settlement's name.

In comparison, several towns in Kent County had larger populations of Black residents than all Lambton County; 737 Black persons resided in Chatham Gore, 669 in Camden Gore, 1252 in Chatham, and 1310 in Raleigh.

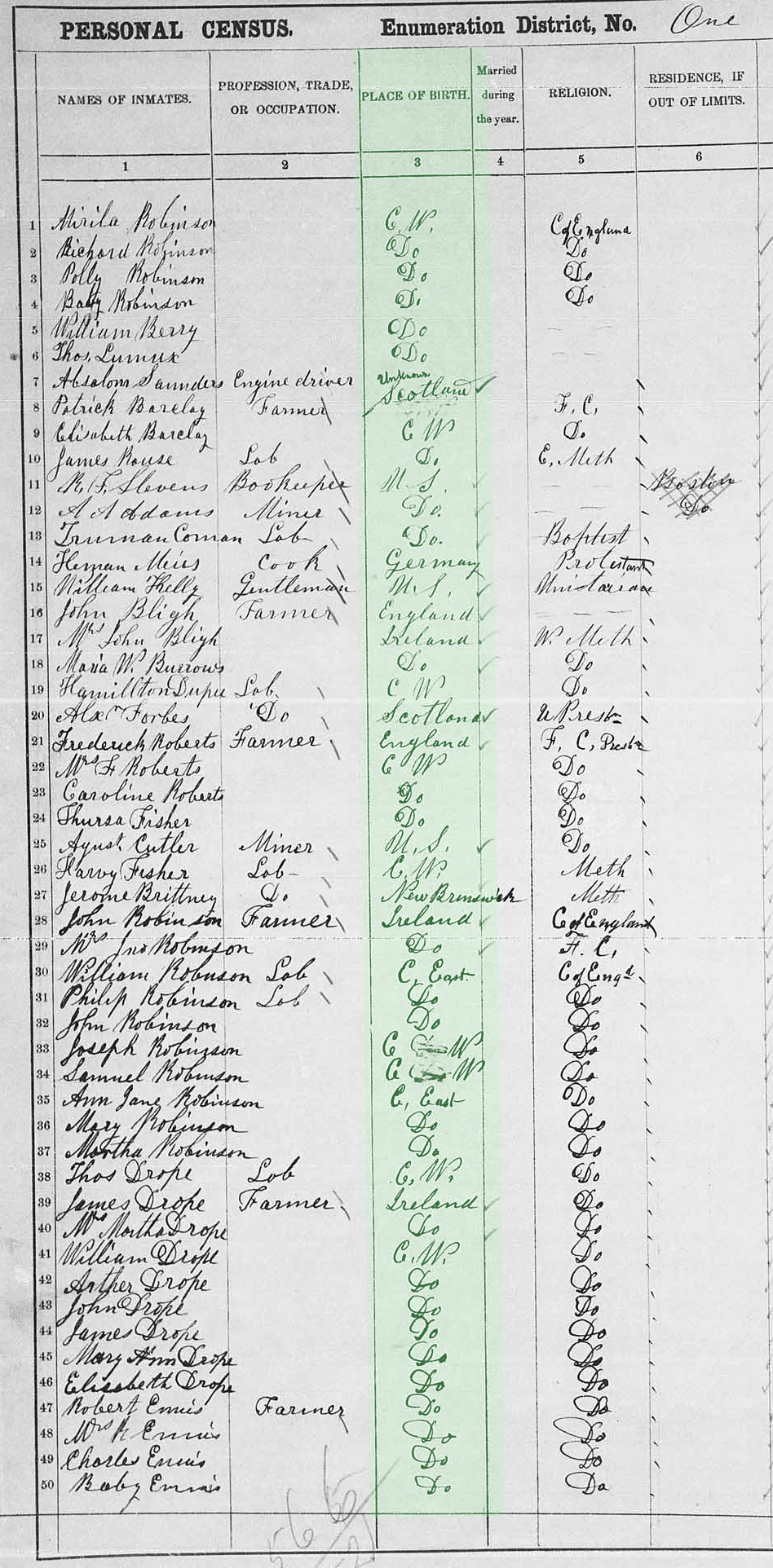

While Black people do not appear in the 1861 census of

Enniskillen or Oil Springs, the riot in 1863 clearly shows that they had moved to the area over the previous two years. This raises a few questions. Why would Black people move to Oil Springs? Where did they move from? Where did they live in town? What kind of work did they do once here?

The first question, “why would they move here,” is easy to answer. Work. The oil boom of Oil Springs was in full swing and wells had popped up across Enniskillen. Oil speculators were getting rich and looking to expand production. Drilling wells, harvesting oil and transporting it took time, muscle, and resources.

Black people were not the only ones to immigrate to the area. As the census excerpt shows, Oil Springs had also become home to Irish, Scottish, English, and American immigrants. The vast majority of Oil Springs residents worked in the oil industry. Some were investors, speculators, or related industry business owners, but most were labourers. The Black community of Enniskillen seems to have largely served as labourers. One account from a Black Chatham resident claims that Black workers in Oil Springs chopped wood for use by local cooperies and larger wells.

The Black people that moved to Oil Springs likely came from a variety of established Black communities in Ontario. The two most commonly cited places are Amherstburg and Chatham.

Historically, materials concerning minority and working-class groups haven't been collected. This has left large gaps in museums' and archives' collections. These gaps are evident when when researching early Black communities in Ontario. Unfortunately, this is the case here and there is little found about the Black population that settled briefly in Oil Springs. The lack of clear records requires turning to other materials, such as newspapers and oral histories, and then reading between the lines of existing collections.

Page from the 1861 Census of Enniskillen.

Memories and stories shared by Oil Springs residents

suggest that Black residents initially lived in temporary shelters on Gypsie Flats and then moved to more substantial lean-tos along Centre Street. Newspaper reports on the riot support

this claim. At the very least, it’s clear that they did not own

the land they lived on--instead, they likely leased or lived on

the land of their employers.

The few records that exist dealing with Oil Springs' Black population centre around the riot. These newspaper articles and court records can help us reconstruct what happened.

Map of Oil Springs with Gypsie Flats and Centre Street highlighted. The Oil Museum is noted by a black diamond.

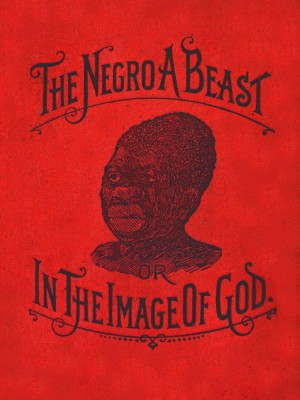

The general consensus of the accounts is that tensions in town had been running high due to the competition between labourers. In particular, white workers were angry at their Black counterparts for working at lower rates. These tensions are not surprising. Black people and other minorities have often been blamed for the financial misfortunes of white populations, and during the 1860s such an accusation was common.

"Up at the oil springs, the coloured people have quite a little town. The white people were there and they had all the work. They charged six shillings for sawing a cord of word. The coloured people went p there from Chatham, and, in order to get constant employment, they charged only fifty cents a cord. What did the white people do? They raised a mob, went one night and burned every shanty that belonged to a coloured person, and drove them off entirely.'

-- Mr. McCullum, Principal Teach of Hamilton High School, 1863-64

However, there is a much larger context to keep in mind. In January of 1863, U.S. President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. The Proclamation freed enslaved persons in the States, and threatened the power structures of white society. Riots occurred across the States in 1863 as tensions rose, and Canada was not immune. Just weeks before the riot at Oil Springs, there was a massive riot in Detroit. The Detroit riot might have served as a kind of spark for the Oil Springs rioters. Letter from the Oil Museum Collection dated 1936. Discusses a re-telling of the riot. A transcript of the letter is included in the alt text.

Letter from the Oil Museum Collection dated 1936. Discusses a re-telling of the riot. A transcript of the letter is included in the alt text.

What escalated the tensions in Oil Springs to the point of a riot is not clear. Some accounts, such as the one in the above letter, cite a Black man pushing a white woman as the spark for the riot. However, we should approach this claim with caution, as it falls into a trend of historic stories that have largely been proven false. Many riots and lynchings began with the story that a Black man had in some way assaulted or insulted a white woman or child. These kinds of stories fall back on one of the stereotypes white society viewed Black people through--the brute caricature.

The Oil Springs race riot took place March 14th, 1863 over the course of a few hours. The general consensus of both reports and oral histories is that rioters gathered under the leadership of one individual. Reports fail to name this leader and give varying accounts of his ethnicity. Some articles claimed the leader was American and others did not mention nationality at all.

After gathering, the rioters marched to the Black settlement on Centre Road. Here, they demanded all Black persons leave town. Rioters set the Black residents' homes on fire before they could respond, knowing no time had been given to comply with the rioters’ demands and that people were still inside. As Black residents attempted to flee their homes, the rioters chased and beat them.

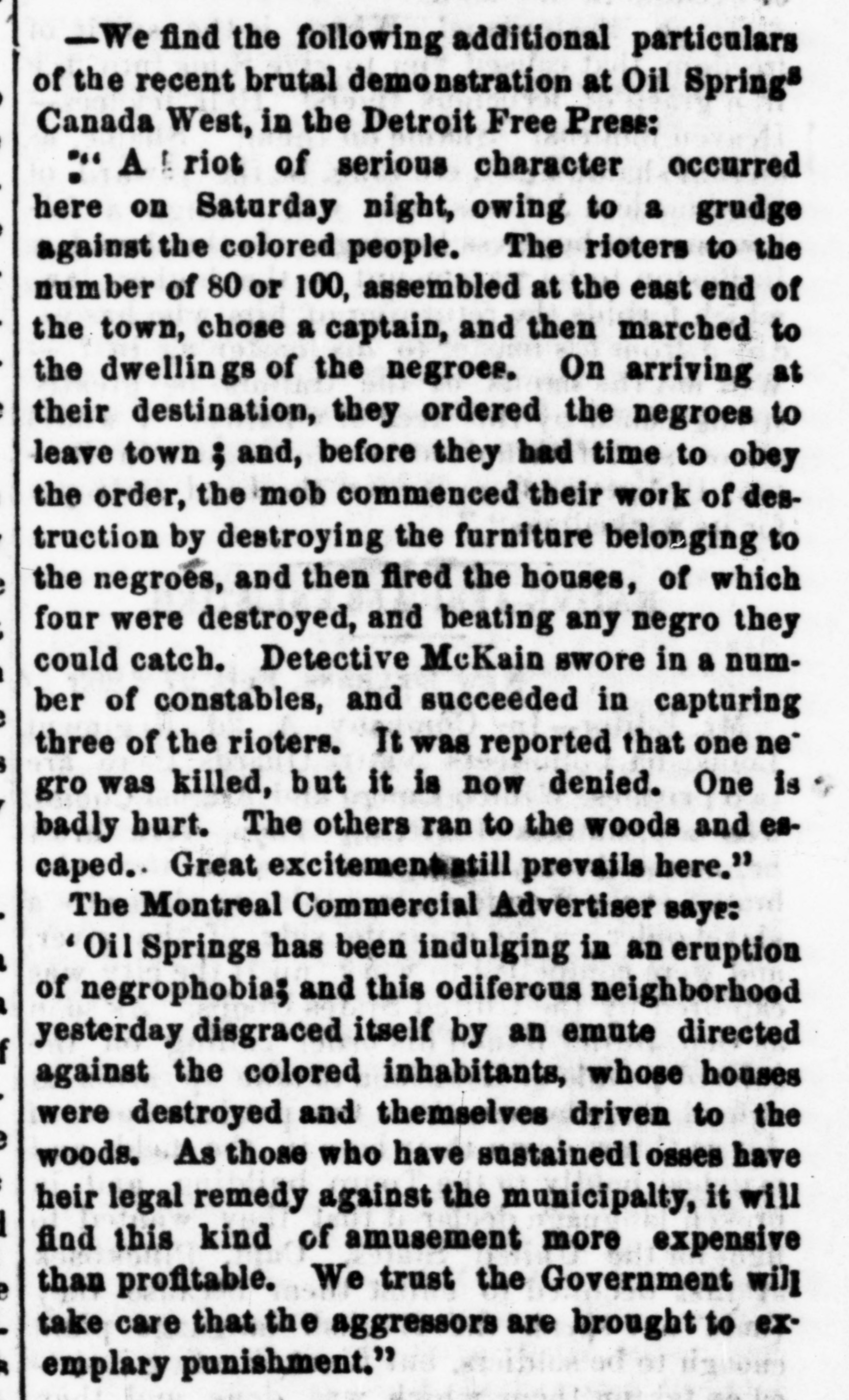

Papers in both Canada and the States condemned the rioters. The Sarnia Observer called the riot a “disgraceful incident” and the Montreal Commercial Advertiser called for the government to punish rioters. The Douglass Monthly, a Black periodical in the States, published articles about the riot, as did the Detroit Free Press.

Despite the violence of the riot and the loud outcry by papers, the consequences to rioters were minimal. Of the several people arrested by local law enforcement, only two faced trial. Of the two people tried, only John Lavins’ records survive. He was convicted of a felony in June of 1863 and received by Kensington Penitentiary (then known as the Provincial Penitentiary of Upper Canada) to serve two years.

Rioters faced no other repercussions. In fact, they achieved their goal--they ran Black people out of Oil Springs for many years to come.

An article from 1936 claims that the next Black person to set foot in Oil Springs came with the Michigan Central Railway. The article claims that, “The villagers were amused to see a tall, broad shouldered, colored chap marching from the west with a gun on his shoulder . . . A Boy Scout in the sense of the word that he was taking the motto ‘Be Prepared’ at its real value, he was making doubly sure that he would not find himself in the same unfortunate position as his former hapless brothers, hence the gun.”

Labourers working in the Lambton County oil fields were key to the growing oil industry in Oil Springs. Black and white labourers’ hard work provided the necessary resources for businesses to not only function, but develop into an innovative industry. However, the ‘better life’ in Oil Springs some Black settlers might have envisioned did not occur.

By sharing the information we can glean from contemporary primary sources, we hope to spark interest in further investigation of the topic. And as more research is conducted and material uncovered, we hope to be able to shed more light on Oil Springs of the past.

Bibliography

“A Disgraceful Riot.” The Sarnia Observer. March 19, 1863. Lambton County Archives. Microfilm.

“Fugitive Slaves in Canada.” The Sarnia Observer. February 6, 1862. Lambton County Archives. Microfilm.

"John Lavins.” Kensington Penitentiary Records, 1863.

Drew, Benjamin. A North-Side View of Slavery: The Refugee, or, The Narratives of Fugitive Slaves in Canada : Related by Themselves, with an Account of the History and Condition of the Colored Population of Upper Canada. Boston, Massachusetts: John P. Jewett and Company, 1856.

Howe, Samuel Gridley. The refugees from slavery in Canada West. Report to the Freedmen's Inquiry Commission, 1801-1876. American Freedman’s Inquiry Commission. United States. 1864.

Lambton County. Census of Canada, 1861. Library and Archives Canada.

Lambton Gazetteer and General Business Directory for 1864-5. Ingersoll: Sutherland Bros, 1864.

Land Records, Enniskillen and Oil Springs. Land Records Office, Ontario, Canada. Accessed via OnLand database.

Letter No. 11. Oil Spring Early History, Box 3, Oil Museum of Canada, Oil Springs, Ontario.

Peter, Ripley C, et al., Editors. Black Abolitionist Papers. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press.

Wayne, Michael. "The Black Population of Canada West on the Eve of the American Civil War: A Reassessment Based on the Manuscript Census of 1861." Histoire sociale / Social History. Vol. 28. 1995. 465-488.

Winks, Robin. The Blacks in Canada, Second Edition. 2nd. Montreal: McGill-Queen's Press, 1997.

"A Disgraceful Riot": The 1863 Race Riot in Oil Springs, Ontario

Created by Keely Shaw of Western University's Public History Program

Subscribe to this page

Subscribe to this page