Teaching in the Classroom

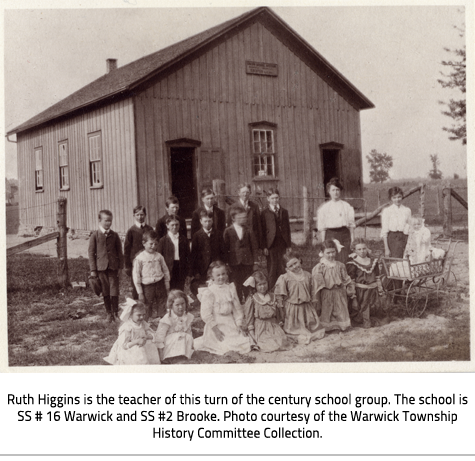

Teaching was a career opportunity for women at a time when their options were limited.

Many of Lambton County's original teachers were retired military men, usually approximately forty years of age, who could no longer do the heavy work of clearing the bush (especially if they had been wounded in battle). This changed in the second half of the 1800s, when teaching became a socially acceptable career for women.

Many of Lambton County's original teachers were retired military men, usually approximately forty years of age, who could no longer do the heavy work of clearing the bush (especially if they had been wounded in battle). This changed in the second half of the 1800s, when teaching became a socially acceptable career for women.

School authorities hired female teachers as they were viewed as “naturally” suitable for the “nurturing role”. Additionally, school boards could save money by hiring women, as they were paid less than their male counterparts. In 1901, 75% of staff employed in education in Canada were women; by 1920, 83% of public school teachers were women.

For some women, teaching offered mobility and financial security. For other women of higher socioeconomic status, teaching represented a step down on the social ladder.

Jean Turnbull Elford's local history book, Canada West's Last Frontier: A History of Lambton reports the following rules for a female teacher in Watford in 1923: “Not to get married. This contract becomes null and void if teacher marries. To be at home between the hours of 8 p.m. and 6 a.m. unless at a school function. Not to wear dresses more than two inches above the ankles.”

An Interview with an Educator: Dr. Christy Rochelle Bressette

Dr. Christy Rochelle Bressette is an Anishinaabe parent, student, teacher, and community member of Kettle and Stony Point First Nation.

Dr. Christy Rochelle Bressette is an Anishinaabe parent, student, teacher, and community member of Kettle and Stony Point First Nation.

Christy was the first Indigenous student at the University of Western Ontario to earn a Ph.D. in Educational Studies and an active supporter of programs designed to empower Indigenous youth and increase parental engagement and community participation in education.

Her late grandfather, David Bressette, gave her the spirit name “Nete Noo-Ke Kwe,” meaning “hard-working woman,” which Christy mentioned is “a name that not only honours me, but all of my ancestors – the ones who worked so hard to ensure that I would be successful today.”

What opportunities do you see in Indigenous education in southwestern Ontario, and what challenges do you see?

Having a good working relationship with the local public school board is and will continue to be key moving forward as we continue to strive for improved educational outcomes for Indigenous learners.

Kettle and Stony Point First Nation is connected to and provides leadership to the Indigenous Education Coalition, in efforts to provide quality culturally-relevant support to 12 indigenous member communities. It also bridging the academic and achievement gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students. This example of mutual respect and collaboration between all education stakeholders (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) toward a common goal of positive education outcomes for all students, concerning Indigenous education, should become a national model.

Read the full interview with Dr. Christy Rochelle Bressette, and to get additional information about Indigenous education.

Subscribe to this page

Subscribe to this page